From a distance, the ghost-pale infant looked lifeless, wrapped in a blanket and tucked in the arms of a woman walking slowly along the steep road that tracks the Arizona-Mexico border wall, about 20 miles east of the Sásabe, Arizona port of entry.

But when Dr. Belen Ramirez got out of her vehicle last Monday, stepping into the cold morning air to assess the 8-month-old girl’s condition, Ramirez found the baby was alive, but very lethargic with shallow breathing.

Ramirez, a family physician with global humanitarian-aid nonprofit Doctors Without Borders, determined the baby likely had low blood sugar. Her Central American mother told the doctor she’d crossed the border into Arizona at 2 a.m., and began the trek toward Sásabe overnight, in search of Border Patrol agents to surrender to.

The nursing mother was barely producing milk, due to dehydration, and was running out of powdered formula, said Ramirez, who has been leading a Doctors Without Borders team in a medical-needs assessment along the Arizona-Mexico border for the past four weeks.

Her team has concluded a dire medical situation exists in this far-flung area of the border where since last fall, large numbers of asylum seekers have been crossing into Arizona and often waiting eight to 12 hours, or in some cases overnight, before they encounter Border Patrol agents they can surrender to.

In the winter months, aid workers reported some waited two or three days in wet and snowy conditions, before agents picked them up for processing.

Anticipating brutal summer conditions, local humanitarian aid groups — now backed up by the visiting team from Doctors Without Borders — are pleading with state and federal agencies to better assist civilian volunteers in their life-saving work at the border wall in Arizona, particularly in this hard-to-reach area east of Sásabe.

“There is a humanitarian medical crisis happening here,” Ramirez said. “We are very worried about the summer months. If they don’t have shelter, if they don’t have water, if they don’t have a timely transport to the area where they’re being processed, it could be fatal.”

Migrants are now facing both cold nights and hot days at the border. Daytime temperatures are still only in the high 80s, but are already perilous for healthy adults who arrive dehydrated, and especially so for those with chronic medical conditions, or those who are very young or elderly, Ramirez said.

For Southern Arizona volunteers who have been sounding the alarm for months, the corroboration from Doctors Without Borders is a relief, said Laurie Cantillo, board chair for Tucson-based Humane Borders, which typically focuses on establishing water stations for migrants deeper in the southern Arizona desert.

Migrant-aid volunteer Elissa McKean, left, sits with an 87-year-old asylum seeker as she rests after climbing a steep hill on her trek toward Sásabe, Arizona in early April.

But the nonprofit requested the visit from Doctors Without Borders last November, after encountering dire medical situations along the border wall, she said.

“It’s validating,” Cantillo said. “A respected, independent medical group agrees there are major medical needs here.”

In a statement to the Arizona Daily Star, U.S. Customs and Border Protection said since last spring, when the surge in migrant surrenders at the southern border began, there haven’t been any deaths among asylum seekers surrendering to agents — although migrant deaths continue deeper in the desert, with more than 4,100 sets of remains discovered in Southern Arizona since 1990, including 40 reported so far this year.

Ramirez said the lack of deaths at the wall east of Sásabe is largely thanks to the dedication of the civilian volunteers acting as first responders. She said the coordinated, volunteer-led response at the border in Southern Arizona is unlike anything she’s seen before.

“I’m personally in awe,” she said. “It’s eye-opening for us to see volunteers from 20 years old to 88 years old. We found an amazing community here.”

Volunteer groups, including the Tucson, Green Valley and Ajo Samaritans, and No More Deaths, have been coordinating for months to ensure a daily humanitarian presence in this hard to reach place, a nearly three-hour drive from Tucson.

Volunteers say Border Patrol has been more responsive to the area in recent months, and now conducts multiple daily pick-ups east of Sásabe, due to pressure from humanitarian groups. But Border Patrol’s transport capacity is still insufficient for the volume of arrivals.

“We’ve noticed a higher degree of cooperation,” said Tucson Samaritan Charlie Cameron. “But we’ve received nothing from any other federal agencies, no responses to our pleas for help. … We’re just reconciled that we’re on our own, and we’re going to continue to have to do it.”

Closed gaps push migrants east

Asylum seekers — sometimes arriving independently, but usually shepherded by human smugglers — have been pushed further east from Sásabe, as gaps in the border wall have been closed by the Biden Administration’s ongoing construction work.

Previously asylum seekers could cross through gaps in the wall just a few miles from the port of entry, but they’re now entering where the border wall ends, as the mountainous terrain becomes impassable.

That’s more than 20 miles from Sásabe, over rollercoaster-steep hills that many vulnerable migrants struggle to climb and that only four-wheel-drive vehicles can navigate, Ramirez said.

Border agents tell volunteers that many of their transport vans can’t scale the steep hills to reach the waiting migrants.

Late last year, No More Deaths established a make-shift camp east of Sásabe, to offer migrants basic shelter as they await border agents and to store aid groups’ supplies.

But as nearby gaps in the border wall have been sealed, the camp is now seven miles from where most migrants are crossing lately, at the end of the border wall.

“If temperatures go up, if people need to walk those seven miles (to the camp’s shelter), I’m 100% certain we’ll have fatalities,” said Andy Winter, a former EMT and migrant-aid volunteer from Vermont who has been living at the camp in his RV for the past three months, assisting migrants daily. “In this country, with the resources we have, that is just shameful and can’t happen.”

Cameron of the Tucson Samaritans is a former National Guard member and he doesn’t understand why the state hasn’t called in the Guard to use their all-terrain vehicles to rapidly transport asylum seekers arriving here.

While the Red Cross provided volunteers with 300 blankets and 400 meals last winter, it’s not enough, he said.

A large shade structure and port-a-potties are desperately needed east of Sásabe, Cameron said, where a sanitation crisis is also brewing, as the rudimentary latrines dug by volunteers are insufficient for the volume of migrant arrivals.

State, federal agencies’ response

Asylum seekers are visible walking along the steep border road east of Sásabe, Arizona, on April 29. A visiting team from global humanitarian-aid nonprofit Doctors Without Borders, or Médecins Sans Frontières, has concluded there's a medical crisis in this location and has asked U.S. Customs and Border Protection to provide a shade structure and water to asylum seekers waiting up to 12 hours for border agents to take them into custody.

Neither CBP, the American Red Cross in Arizona, nor the Arizona Department of Emergency and Military Affairs, known as DEMA — the agency responsible for emergency response in the state — gave an interview in response to the Arizona Daily Star’s request. They only provided emailed statements.

“We are constantly monitoring the dynamic and complex situation on the Arizona border,” said Gabe Lavine, DEMA’s emergency management director, in a statement.

But state agencies can only be involved at the border wall at the direct request of CBP, which has jurisdiction over the land adjacent to the border wall, except on sovereign tribal lands, Lavine said.

In this case, CBP “has not requested assistance, and has not indicated to us that their contracts and resources are inadequate,” Lavine said. “We are hesitant to take action on federal lands without an unambiguous invitation by the federal government.”

Ramirez said her team was able to meet with Justin De La Torre, deputy chief of the Border Patrol’s Tucson sector, and CBP’s chief medical officer, to share her organization’s concerns. The team has a follow-up meeting with De La Torre scheduled within the next week, and Ramirez hopes to hear the agency’s plans to boost humanitarian resources east of Sásabe, she said.

In an emailed statement, CBP’s assistant public affairs commissioner Erin Waters said CBP adjusts resources in response to shifting migration patterns.

“The fact remains that we continue to experience serious challenges along our border; we need Congress to take action and provide additional resources and tools to address them,” she said.

An additional CBP statement said that, east of Sásabe, “the Border Patrol has surged personnel and transportation resources to respond to the increase in encounters in the area — some of the hottest, most isolated, and dangerous area of the southwest border — where individuals have been callously sent by smuggling organizations to walk for miles, often with little or no water.”

Tucson sector chief John Modlin was not available for an interview last week, but CBP annually holds press conferences, most recently in March, warning migrants of the mortal danger of crossing the border illegally, particularly in the summertime.

“The sheer volume of people crossing here magnifies these risks,” Modlin said at the March event. “It puts every life at more peril than ever before, from every single adult trying to evade our agents, to infants being carried by their families into this unforgiving environment.”

For Cantillo, that’s all the more reason for federal agencies to make more plans now to avoid crises this summer.

“The Border Patrol itself has said this is likely to be a dangerous and deadly summer,” Cantillo said. “With Sásabe, we all know what’s coming. Why wait until the numbers are so high, and people get sick and die out there? Why not get ahead of this and establish a temporary shade structure at the end of the wall?”

Cameron said border agents communicate with aid workers about their pick-up schedules, usually three times a day and one overnight pick-up, and are often grateful for the status updates shared by volunteers on the border.

“I know many of these border agents would do whatever they could to save them,” he said. “But they don’t have the resources and the support to do that.”

But other agents are hostile to volunteers, threatening them with arrest if they transport a migrant with urgent medical needs to the Border Patrol station, Winter said. As long as advocates are not furthering the journey of migrants, and are taking them directly to Border Patrol, they’re not violating the law, volunteers say.

“They actually chase us off the wall,” Winter said. “They threaten us with arrest. They accuse us of all sorts of things, like working for the cartels, when folks are just out there providing food and water, first aid, and occasionally people are transported.”

Arrivals up in Sásabe

Border-wide, the number of migrant apprehensions was down in April, a departure from the usual spring-time surge, according to the Washington Office on Latin America. The decrease is likely related to Mexico’s crack-down on migrants traveling northward, which advocates say came at the behest of U.S. officials and has resulted in an increase in abuses suffered by migrants.

Yet in the past few weeks, arrivals east of Sásabe have surged, aid workers say. Over the fall and winter, arrivals here often topped 400 people per day, while earlier this year some days there were just a handful of arrivals, or none.

But lately, between 100 and 200 migrants have been arriving most days, volunteers told the Star.

Asylum seekers crest one of the steep hills along the Arizona-Mexico border, east of Sásabe, Arizona, in early April.

Migration patterns are always evolving and depend on many factors, Ramirez said. Outbreaks of violence between criminal factions south of the border wall in Sonora influence where smugglers decide to drop off migrants at the border wall.

Last year aid workers working out of the small border town of Sàsabe, Sonora, Mexico, said a war that broke out between criminal factions there, sending hundreds of residents fleeing to the U.S. and shifting smuggling routes both further east of Sásabe, and further west toward Lukeville and the Tohono O’odham Nation.

U.S. policy drives chaos, advocates say

Human rights advocates say U.S. border policy compels many asylum seekers to make dangerous journeys by failing to provide legitimate, safe means of requesting asylum, or seeking work visas, at U.S. ports of entry, where infrastructure already exists to receive them.

Instead, deterrence policies encourage asylum seekers to cross between ports of entry, not only putting them in danger but also burdening border agents, whose primary mission is supposed to be intercepting illegal activities and apprehending migrants who try to evade border agents.

Agents have been devoting most of their time and resources to processing migrants who willingly surrender, Tucson sector chief Modlin has told the Star.

While it’s legal for someone to request asylum once they’re on U.S. soil — no matter how they entered the country — the current arrangement defies logic, and endangers vulnerable people, said Aryanna Tischler of No More Deaths.

“Every port of entry should process asylum seekers,” Tischler said. “That’s a really simple decision within the government to change this policy, which would avert this crisis that’s happening all along the border.”

The Biden Administration has touted its CBP One smart phone application as the only legitimate means of securing an appointment to request asylum for most migrants.

A group of migrant use a make-shift hammock to carry an 18-month-old child up one of the steep hills along the border road east of Sásabe, Arizona in early April.

But the DeConcini port of entry in Nogales is the only port that accepts CBP One appointments in the 700 miles between Calexico, California, and El Paso, Texas, and it only accepts 100 appointments a day, according to the Kino Border Initiative.

Thousands of migrants are currently camped along the Mexico side of the U.S.-Mexico border, trying to enter the U.S. “the right way,” advocates say. Numerous human rights groups — including Human Rights First and Doctors Without Borders — have reported on the grave dangers would-be asylum seekers face as they wait, including rampant kidnappings, extortion and assault.

For many, the risks of waiting are too great. In Arizona, aid workers say they’ve encountered migrants who had been waiting more than eight months for a CBP One app appointment in Nogales, Sonora. Eventually they ran out of money, or feared for their lives, and decided to cross between ports of entry out of desperation.

Advocates say the requirement to use CBP One is an impossible hurdle for many asylum seekers. The smart phone app is beset by glitches, and inaccessible to migrants without the right kind of smart phone, or access to WiFi.

“We’re making it difficult for people to come in a regular way,” Ramirez said. “Nobody takes this route (crossing between ports of entry) for fun.”

Those who don’t use the CBP One app will eventually be denied asylum and face bans on re-entry when they have their asylum hearing — but for most, those decisions are years away, due to U.S. lawmakers’ failure to adequately fund the overwhelmed asylum court system, advocates say.

U.S. immigration courts now face a backlog of 3 million cases, according to data from Syracuse University researchers who manage the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, or TRAC.

Despite the dangers and despair for those waiting at the border, volunteer Winter said he’s witnessed acts of generosity and courage among the migrants he’s encountered in his three months camping east of Sásabe, including families taking unaccompanied minors under their wing, like the 5-year-old unaccompanied girl Winter saw picked up by border agents.

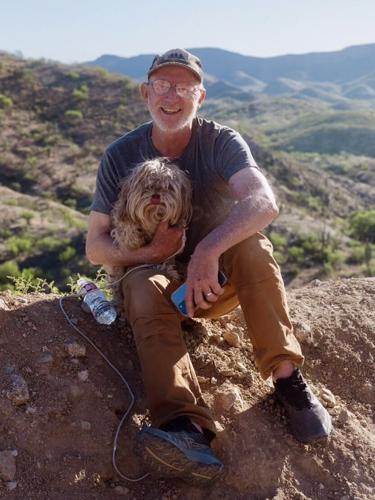

Migrant-aid volunteer Andy Winter sits near the Arizona-Mexico border with his dog Rafa, who has become a kind of therapy dog for young asylum seekers they encounter at the border.

Winter said he’s seen migrants refuse water from volunteers, saying there’s someone up the road who needs it more.

“It’s just people helping people, carrying other people’s children. They’ve gone through hell and they’re still hopeful, and they’re still resilient, and they’re still trying to protect each other,” Winter said. “That’s an amazing thing to witness. They’ve inspired me to work harder and actually be a better person.”

See what the top sports stories are for UA and Tucson.