This Tucson anniversary was brought to you by men behaving badly.

One hundred and fifty years ago this month, the soldiers at Camp Lowell packed up their gear in present-day Armory Park and marched to a new post near the Rillito River, about 7 miles outside of town.

The U.S. Army had plenty of reasons to withdraw its troops from the heart of Tucson in March of 1873. The original Camp Lowell was cramped, unsanitary and poorly equipped, with soldiers forced to bunk in tents. And the site’s proximity to the Santa Cruz River exposed the men to mosquito-borne malaria.

But complaints from townspeople also played a role. Apparently, the locals were fed up with soldiers getting drunk and picking fights with them.

“They had a lot of problems with that,” said historical archaeologist Homer Thiel with Tucson-based Desert Archaeology. “They wanted a location far away from the saloons and the civilians and the prostitutes.”

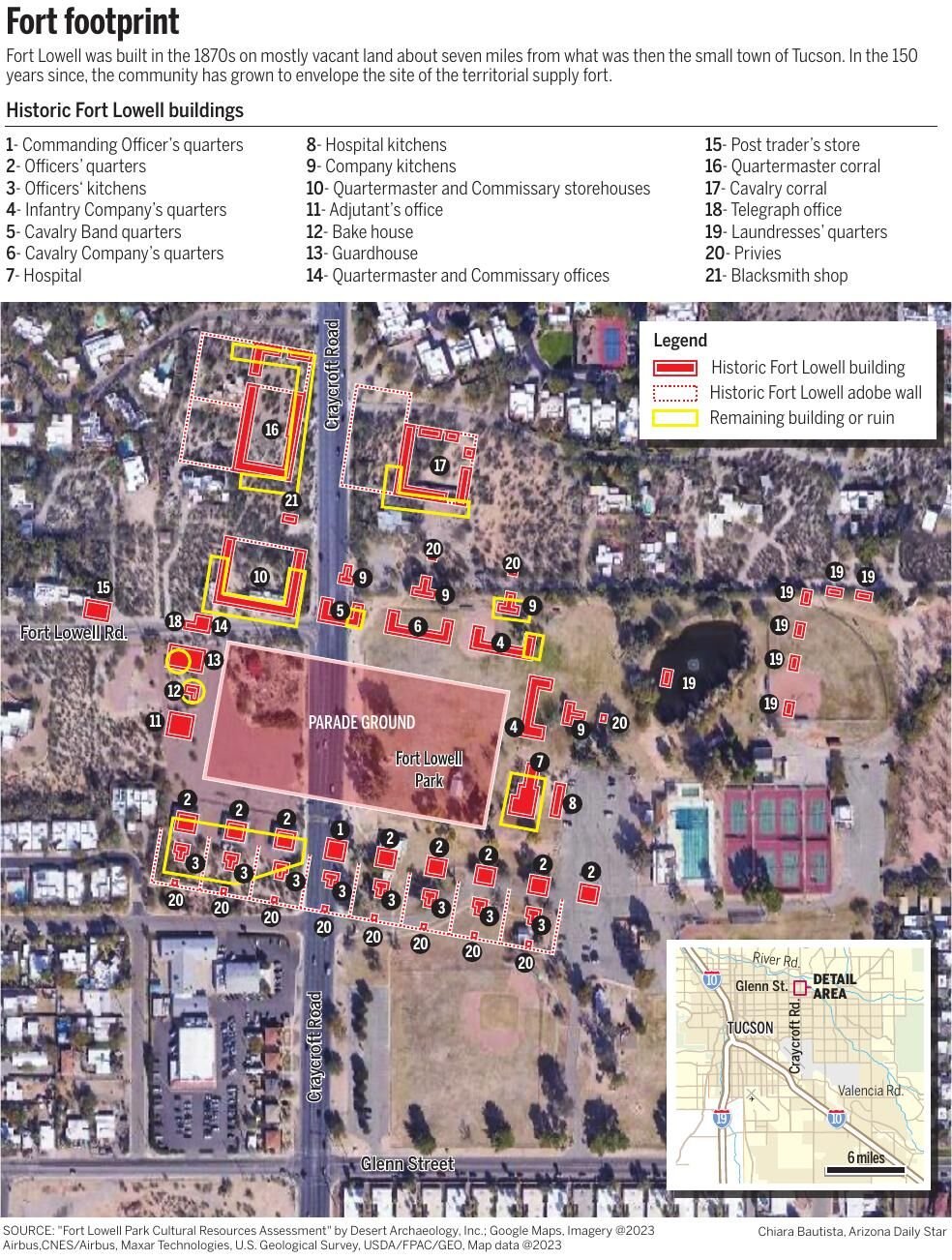

So began construction of the 200-acre supply depot that would become Fort Lowell.

The Army chose the site near the confluence of Tanque Verde Creek and the Pantano Wash for its ready access to water and ample grass for livestock.

The troops initially lived in canvas tents, but construction soon began on permanent structures, starting with the guardhouse and a building for the commanding officer.

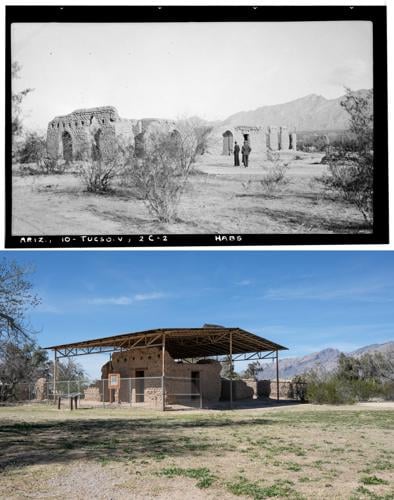

Top: The post hospital ruins at Fort Lowell in 1937 in a photo from the Historic American Buildings Survey during the Great Depression. Bottom: Today, a metal cover at Fort Lowell Park shields part of the decaying post hospital from further damage from weather and sun.

Top: The parade grounds and a deteriorating cavalry barracks at Fort Lowell with an unimpeded view of the Santa Catalina Mountains, probably in the early 1900s. Bottom: Fort Lowell Park today, with mature trees, ball fields and lots of homes between the old fort and the mountains.

The production of adobe bricks went to the lowest bidder — $30.06 per 1,000 bricks from a Tucson company called Lord & Williams that would later report heavy losses from its contracts supplying the Army.

Pine beams were hauled down from the Catalina Mountains to support roofs made with saguaro ribs covered in packed earth. The buildings would leak and drip mud during monsoon storms, until tin roofs were finally installed starting in late 1879, the same year the former camp was officially designated as a fort.

Lowell eventually grew to include more than 30 structures, all built around a central parade ground bordered to the south by two rows of irrigated trees that came to be known as Cottonwood Lane.

Across the lane from the parade ground was a line of nine houses set aside for the officers, each with its own kitchen, garden and outhouse. The commanding officer’s quarters sat in the middle of the line, roughly where northbound traffic on Craycroft Road now cuts through the grounds of the old fort.

To ensure a good supply of water and forage for Lowell, the federal government also claimed the 80 square-miles to the east of the fort as a military reservation. Some 17 ranches between the fort and the Rincon Mountains were seized by the government over the complaints of their owners, who felt they were not sufficiently compensated.

Many of the civilians living on the military reservation refused to leave, Thiel said.

A panorama between two existing, deteriorated adobe officers' quarters buildings at Fort Lowell, on the west side of Craycroft Road, looking north, on March 1.

During the 1870s and 1880s, Lowell served as a supply depot for other camps and forts in Arizona.

The cavalry and infantry units stationed there were responsible for escorting wagon trains, protecting nearby settlers, guarding supplies, patrolling the border and conducting offensive operations against the Western and Chiricahua Apache tribes, including the forced relocation of native people to reservations.

The fort averaged about a dozen officers and 200 enlisted men, though those numbers rose in 1883 as the Army stepped up its campaign against the Apaches.

With the surrender of Geronimo in 1886, conflicts with the Apache people declined and non-native settlers poured into Tucson, fueled by the arrival of the railroad six years earlier.

In early 1891, U.S. Army Commanding General John Schofield ordered Fort Lowell to be abandoned, over the objections of community members in Tucson who wanted the garrison to stay.

Top: “Cottonwood Lane” at old Fort Lowell in 1888, with officers’ quarters to the right. Bottom: The original Cottonwood trees and officers’ quarters are gone. The fort museum, a replica built in 1963, is at right. The recreated Cottonwood Lane, planted by the county in 1963, is narrower than the original and not in the original place.

The last soldiers left the fort on Feb. 14, 1891. Two months later, the property was transferred to the Department of the Interior to be sold as surplus.

That November, two Tucson men rode their bicycles out to the site and described what they saw to the Arizona Daily Star: “They report that the trees along the avenues of the fort are dying for want of water and the work of more than fifteen years is rapidly going to wreck and ruin.”

The Army returned the following year to dig up the remains of 80 people buried in the post’s graveyard and move them to the National Cemetery at the Presidio in San Francisco.

The surplus property auction was finally held on Nov. 18, 1896, and raised $1,080. A list of the buildings sold and who purchased them can be found at the National Archives.

The winning bidders stripped the structures of their windows, doors, wood floors, roof beams and tin, with much of that material used to build homes elsewhere in Tucson.

Much of the remaining adobe was left to decay in the weather or at the hands of vandals.

“Even by the turn of the century, it was a ruin,” said Elaine Hill, who chairs the city’s Fort Lowell Historic Zone Advisory Board.

Deteriorating adobe walls of one of three existing officers' quarters building at Ft. Lowell west of Craycroft Road on March 1.

Pre and post

The fort’s 18-year run was just one brief chapter in the much longer and more diverse story of the area.

Thiel and other archaeologists have found evidence of human habitation along this stretch of the Rillito River dating back as far as 650 A.D. and persisting for centuries.

“Water is what drew people to places like this,” he said. “Water is the main thing.”

Enough prehistoric sites have been found in and around Fort Lowell Park to suggest the presence of a major Hohokam settlement that was long-lasting and likely home to a large number of people, Thiel said.

During an archaeological investigation in 2012, he helped identify 10 Hohokam pit houses on a single 5-acre parcel of city-owned land across Craycroft from the park. In one of the pits, he and his team unearthed a piece of plaster with grooves in it left by human hands approximately 1,100 years ago.

“That’s pretty amazing to see somebody’s fingerprints from that time,” Thiel said.

The 2012 investigation also turned up relics from when the fort was in operation, including evidence of gardens planted by the officers’ Chinese servants, scattered pieces of ammunition and a gilded bronze flagpole tip, perhaps lost on the parade ground by one of the cavalrymen.

After the Army abandoned Lowell, Mexican farmers and ranchers began moving into the area, forming a community known as El Fuerte. The new residents repurposed some of the fort’s old buildings or built adobe homes of their own, a few of which still stand today.

Though El Fuerte has largely disappeared, the San Pedro Chapel — built by Mexican families in 1932 to replace an earlier church that was destroyed by a tornado — has been added to the National Register of Historic Places and remains the centerpiece of what is now known as the Old Fort Lowell Neighborhood.

Efforts to preserve the ruins of the fort have been going on for almost a century.

In the early 1900s, the still-abandoned parts of the fort became a popular picnic spot for souvenir hunters from Tucson and a camping destination for the University of Arizona’s military cadet program and the Boy Scouts.

Tucson’s newly formed scout troop first marched out to the fort for a week-long campout in April 1912 and later owned the property in the 1940s and 1950s. The shelter that protects what’s left of Fort Lowell’s hospital was built by the Boy Scouts.

Thiel said the fort’s crumbling adobe walls also attracted several silent movie productions, including 1918’s “Headin’ South,” starring Douglas Fairbanks, and 1919’s “Chasing Rainbows,” about a jilted waitress who moves to the desert and falls in love with her boss.

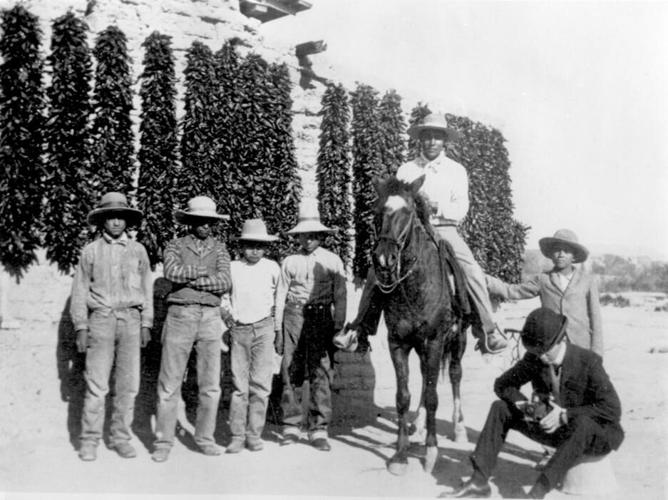

Fuertenos workers and a photographer outside the Fort Lowell commissary, now the corner of Ft. Lowell and Craycroft roads, in 1910. Chiles were grown near Rillito and Pantano rivers.

The early 1900s also saw at least three private sanitariums pop up in and around Fort Lowell for people with tuberculosis and other chronic illnesses. One sanitarium operated out of the old officers’ quarters on the west side of Craycroft, while another opened on the north side of Fort Lowell Road in what used to be the Post Trader’s Store, built in 1873 to serve the troops at the fort.

The old store was later bought by Charles, Pete and Nan Bolsius and transformed into a sprawling home and studio befitting the artist colony that sprang up in the neighborhood through the 1940s. Among the prominent artists and intellectuals who lived in the area were French artists René and Germaine Cheruy, anthropologists Edward and Rosamond Spicer, photographer Hazel Larson Archer and modernist painter Jack Maul.

Jack Kerouac immortalized the neighborhood in “On the Road,” after he drifted through to visit his writer friend Alan Harrington in the late 1940s. In the novel, Kerouac describes Tucson as “one big construction job” “situated in beautiful mesquite riverbed country, overlooked by the snowy Catalina range.”

The first serious efforts to save what was left of Fort Lowell took place in the late 1920s, when history buffs and tourism boosters with the Tucson Chamber of Commerce requested that the site be protected as a State Historic Monument.

In 1929, a 40-acre portion of the old fort was withdrawn from homesteading or sale and set aside as state trust land. Three years later, a bill was introduced in Congress to turn Fort Lowell into a national monument, but the measure failed to pass.

Pima County eventually acquired the land from the Boy Scouts in 1957 and promptly closed off the ruins to protect them from vandals while plans were drawn up to turn the area into a recreational park.

The Fort Lowell Historical Museum opened inside a specially built replica of the commanding officer’s quarters in 1963, as the rest of the park was still being developed around it. That building is now old enough to be considered historic in its own right.

“There’s a long history of attempted preservation,” said Hill, who has lived in the Old Fort Lowell Neighborhood for 30 years. “It speaks to past generations’ efforts to preserve this place.”

Amy Hartmann, executive director of the Presidio San Agustin del Tucson Museum, which has assumed management of the Fort Lowell Museum, shows neighborhood residents a model of historic Fort Lowell at the temporarily-closed museum on March 1.

New management

Fort Lowell’s history — or at least the museum dedicated to it — is now under new management.

In December, the Tucson Presidio Trust for Historic Preservation entered into an agreement with the city to take over operations at the Fort Lowell Historical Museum.

Prior to that, the Arizona Historical Society ran the small, admission-free museum for more than 30 years, before pulling out in October 2020 amid cost cutting by the nonprofit agency.

Tucson City Councilman Paul Cunningham, whose Ward 2 includes Fort Lowell Park, called the new agreement “a great opportunity for the city,” which acquired the museum and the park surrounding it in 1984.

“It’s a natural fit to have the Tucson Presidio Trust take over the Fort Lowell Museum,” Cunningham said in a written statement. “We finally get to activate the historical piece of the park in the way many have visioned it to happen.”

The nonprofit trust also runs the Presidio San Agustín del Tucson Museum downtown.

The museum in Fort Lowell Park is now in the midst of major repairs to its adobe exterior and other improvements.

Presidio Museum executive director Amy Hartmann-Gordon said the building needed more work than originally thought, but the renovation is progressing nicely. She is hopeful they could be ready to reopen by the fall.

The museum shut down on April 1, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and it has been closed ever since.

The historical society has removed all the artifacts from the building and placed them into storage for safekeeping, but Hartmann-Gordon isn’t worried about that. She said the Presidio Museum has a great relationship with the historical society, and she is confident they can work out an agreement to bring the artifacts back, possibly on permanent loan, once the building is ready to house them again.

W. Mark Clark, board president of the Tucson Presidio Trust, said plans are in the works to update and expand the museum’s offerings to better tell what he called “the full story, not just bugles and sabers and fancy hats and horses.”

Hartmann-Gordon said that will include a greater effort to explain the fort’s impact on the native inhabitants of the area, including the Apache people.

“We will never rewrite history, we will never change the facts,” she said, “but more than ever it is important that when we talk about history, it needs to be inclusive of lots of different views, and that hasn’t always been done in the past.”

Visitors should not expect “a brand new set of exhibits” right away, Hartmann-Gordon said. The changes will be gradual, an ongoing evolution much like the one underway at the Presidio Museum.

“I want to make sure people understand that this is a process,” she said.

Eventually, the city hopes to expand the historical offerings beyond the current boundaries of the park, with help from the Presidio Trust, the Old Fort Lowell Neighborhood Association and other partners.

Within the last decade, protective shelters have been built over the ruins of two officers’ quarters across Craycroft from the park, and a third officers’ quarters has been restored enough to one day welcome visitors inside again.

Next up, city officials plan to use Proposition 407 bond money, approved by Tucson voters in 2018, to complete similar preservation work on two historic buildings on either side of Craycroft just south of the park: the old fort commissary and a house built by the Donaldson family in the 1940s on the site of the fort’s horse corral.

The goal is to open those city-owned properties to the public some day, possibly as cultural attractions, event space or even as galleries or other commercial ventures.

Clark hopes the area’s rich past — before, during and after its days as a fort — will play a central role in whatever gets developed there in the future.

“The history of that area is fascinating,” he said. “I think it’s a uniquely Tucson story.”

Photos: Historic Fort Lowell and Fort Lowell Park in Tucson

Fort Lowell, Post Hospital (Ruins), 1937. Historic American Buildings Survey, John P. O'Neill, photographer.

A panorama between two existing, deteriorated adobe officer's quarters buildings at Fort Lowell, on the west side of Craycroft Road, looking north, on March 1, 2023.

Deteriorating adobe walls of one of three existing officer's quarters building at Ft. Lowell west of Craycroft Road on March 1, 2023

Refurbished Fort Lowell officer's quarters building on the west side of Craycroft Road on March 1, 2023.

Back side of the officers' quarters at Fort Lowell in 2013, just west of Craycroft Road, prior to renovation by Pima County.

Amy Hartmann-Gordon is executive director of the Presidio San Agustin del Tucson Museum, which has assumed management of the Fort Lowell Museum, shows neighborhood residents a model of historic Fort Lowell at the temporarily-closed museum on March 1, 2023.

Interior room of a officer's quarters building at Fort Lowell that has been refurbished, shown on March 1, 2023

East elevation of the Fort Lowell Officers' Quarters (probably closest to Craycroft Road, west of the park) in 1940. Historic American Buildings Survey. Donald W. Dickensheets, photographer.

Termite-damaged, decayed beam at one of the Fort Lowell officer's quarters west of Craycroft Road on March 1, 2023.

Top: The parade grounds and a deteriorating calvary barracks at Fort Lowell with an unimpeded view of the Santa Catalina Mountains, probably in the early 1900s. Bottom: Fort Lowell Park today, with mature trees, ball fields and lots of homes between the old fort and the mountains.

Top: "Cottonwood Lane" at old Fort Lowell in 1888, with officers' quarters to the right. Bottom: The original Cottonwood trees and officers' quarters are gone. The fort museum, a replica built in 1963, is at right. The recreated Cottonwood Lane, planted by the county in 1963, is narrower than the original and not in the original place.

Top: The post hospital ruins at Fort Lowell in 1937 in a photo from the Historic American Buildings Survey during the Great Depression. Bottom: Today, a metal cover at Fort Lowell Park shields part of the decaying post hospital from further damage from weather and sun.

The now-open, rock-lined basement, shown on March 1, 2023, under the storehouse at Fort Lowell was used for longterm food storage. The standing buildings of the old storehouse were converted to residences after the fort was abandoned. The City of Tucson now owns the property.

Undated photo of soldiers eating at Fort Lowell, ca. 1880s.

The quartermaster and commissary storehouse at Fort Lowell on Fort Lowell Road, west of Craycroft Road on March 1, 2023. The original buildings were modified and converted to residences after the fort was abandoned. The City of Tucson now owns the property.

The Bolsius home, photographed in 1954. It is formerly the sutter's store, built ca. 1870, at the Ft. Lowell calvary post, 5425 E. Ft. Lowell Road.

Ft. Lowell neighbors stand on the former parade ground during a tour of the historic fort area on March 1, 2023.

Though El Fuerte has largely disappeared, the San Pedro Chapel – built by Mexican families in 1932 to replace an earlier church that was destroyed by a tornado – has been added to the National Register of Historic Places and remains the centerpiece of what is now the Old Fort Lowell Neighborhood.

Fuertenos workers and a photographer outside the Fort Lowell commissary, now the corner of Ft. Lowell and Craycroft roads, in 1910. Chiles were grown near Rillito and Pantano rivers.

Flag ceremony at pre-camporee training course at Ft. Lowell, October 1950. Tucson’s newly formed scout troop first marched out to the fort for a week-long campout in April 1912 and later owned the property in the 1940s and 1950s. The shelter that protects what’s left of the fort’s hospital was built by the Boy Scouts.

The Donaldson House, which was part of the corral area at historic Fort Lowell, shown on March 1, 2023 It is now owned by the City of Tucson.

The Adkins home and water tower on the Fort Lowell property at the southwest corner Craycroft and Ft. Lowell roads on March 1, 2023. That home was not an original fort building. It was built after the surplus property was auctioned by the government. For years, it was a metal fabrication business.

"Cottonwood Lane" at old Ft. Lowell, the colorful cavalry post's housing area, looked like this in 1888. Trees were planted this week to duplicate the street's former aspect.

Visitors crowd around the reproduction of the new commanding officer's quarters during a dedication of the Ft Lowell Historical Museum on Veteran's Day, November 11, 1963. Located on Cottonwood Lane (note the trees in the background).

The officers' quarters at Fort Lowell Park went through renovation in March 1963 and became the current-day museum.

Cottonwood trees along "Cottonwood Lane" at Fort Lowell/Fort Lowell Park. The Ft. Lowell Museum (not an original fort building) is undergoing renovation in the background on March 1, 2023.

Workers reconstruct the porch around the Fort Lowell Museum at the park on March 1, 2023. The building was is one of the original fort structures.

Fort Lowell, Post Hospital (Ruins) in 1937. Historic American Buildings Survey. Frederick D. Nichols, photographer.

Fort Lowell hospital in 1967.

Graffiti in the adobe walls of the post hospital at Fort Lowell in Tucson on March 8, 2023. The building has been fenced off for several years.

The post hospital at Fort Lowell in Tucson on March 8, 2023. The building has been fenced off for several years.

Civil War reenactors in period costumes at Ft. Lowell Park in 1991.

1st Calvary E Troop, Mesa; 4th Calvary B Troop, Ft. Huachuca; and 6th Calvary E Troop, Tucson; demonstrate their horsemenship at Ft. Lowell Park in 1985.

In this 1981 photo, David Faust, curator of the Ft. Lowell Museum, works with members of the Youth Conservation Corps to repair adobe walls at the Ft. Lowell hospital, built in 1873.

Fort Lowell Historic District sign an adobe wall behind it in 1979.

The Fort Lowell hospital at Ft. Lowell Park in 1979.