Two “mystery booms” rolled into Tucson from the west last month, rattling windows and triggering local seismic equipment in a way that suggests disturbances in the sky, not underground, according to a new analysis by geoscientists at the University of Arizona.

Seismologist Susan Beck and her colleagues compared data collected by Tucson’s main seismic station near Sabino Canyon to readings captured by a growing network of backyard sensors to determine the speed and direction of booms reported on Jan. 10 and 25.

An undated photo shows the building at the base of the Catalina Mountains that houses a seismograph known as TUC, which is part of the Advanced National Seismic System.

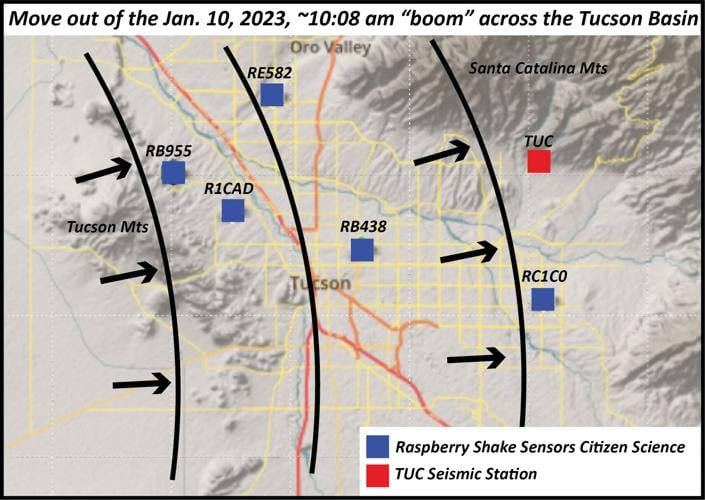

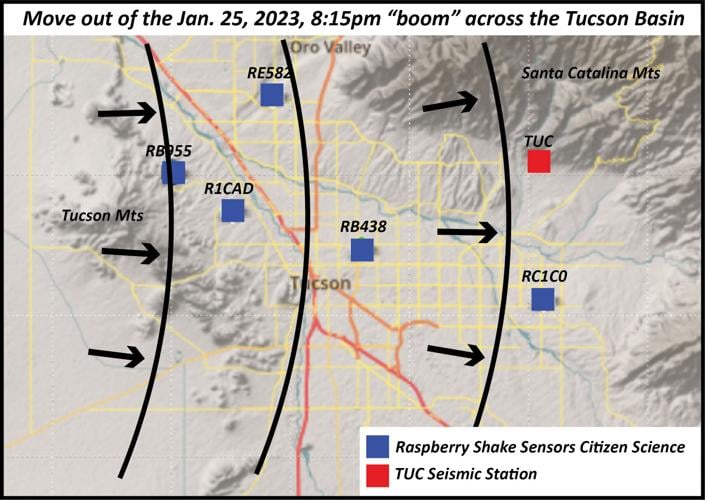

What they found was the clear signature of an atmospheric disturbance moving from west to east at roughly the speed of sound.

The findings bolster the case that sonic booms — almost certainly from military aircraft — are responsible for the occasional house-shaking rumbles that Tucson residents have been experiencing for years.

“I’m sure it’s not an earthquake. I think we can rule that out,” said Beck, a professor in the UA’s Department of Geosciences. “I think the cause is in the air, and based on eliminating other sources, it’s probably planes.”

The path of the two booms last month — one at approximately 10:08 a.m. Jan. 10, the other at 8:15 p.m. Jan. 25 — suggest they came from the direction of the Barry M. Goldwater Range, the 1.9-million-acre military training ground in southwestern Arizona that stretches across parts of Pima, Maricopa and Yuma Counties.

But Beck stressed that they do not have enough information to say for certain what or exactly where the two booms came from.

To pinpoint the location of future booms, she said, they will need to tap into seismic stations outside of Tucson, preferably at least one near Yuma so they can narrow in on the Goldwater Range as the possible source.

Booms travel a long way

A sonic boom is the result of shock waves created by an object moving faster than the speed of sound, or about 750 mph at sea level. The sound heard on the ground is the sudden onset and release of pressure as the shock wave passes.

The size of the exposure area from the boom increases by approximately 1 mile for every 1,000 feet of altitude, so a supersonic jet flying at 30,000 feet will create a boom impacting roughly a 30-mile area, according to a U.S. Air Force fact sheet on sonic booms.

Atmospheric conditions and maneuvers made by the aircraft can change the strength and direction of the shock waves.

If the mysterious rumbles on Tucson’s west side are coming from aircraft training at the Goldwater Range, those booms are traveling a long way to get here. The eastern edge of the range is about 75 miles from the intersection of Interstate 10 and Ina Road, as the A-10 Thunderbolt flies.

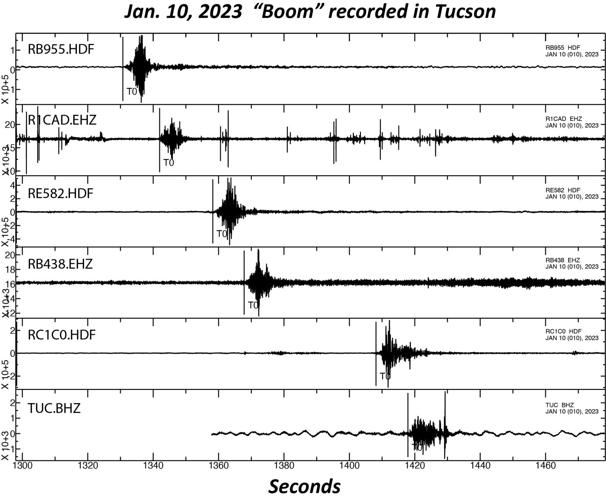

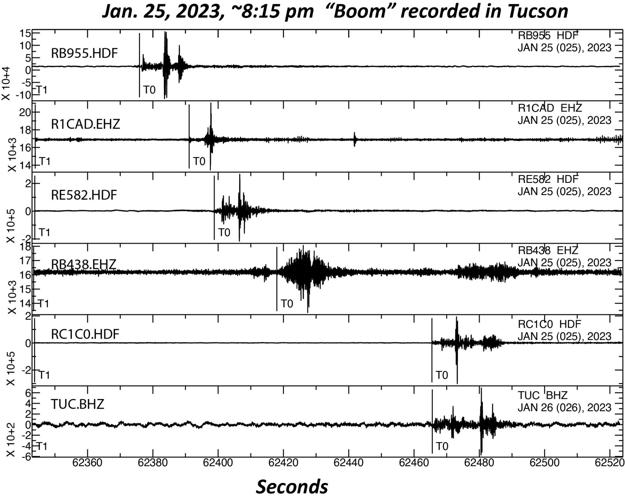

The plots from six different local seismographs show the signal from a boom that was reported in Tucson on Jan. 10.

A map shows the movement of vibrations from a boom that was picked up by seismographs in Tucson on Jan. 10.

The plots from six different local seismographs show the signal from a boom that was reported in Tucson on Jan. 25.

A map shows the movement of vibrations from a boom that was picked up by seismographs in Tucson on Jan. 25.

The sounds could also be coming from jets that are breaking the sound barrier while flying to or from the range, but Beck said she has no evidence to support such speculation.

The public affairs offices at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base and Morris Air National Guard Base in Tucson and Luke Air Force Base in Phoenix did not immediately respond to questions about sonic booms and the two incidents in January.

Military pilots train at supersonic speeds to simulate real-world battle scenarios, but whenever possible, those exercises are conducted over open water, above 10,000 feet and at least 15 miles from shore.

Air Force procedures require that supersonic flights over land must be conducted above 30,000 feet or in specially designated areas approved by the Air Force and the Federal Aviation Administration.

More booms could be on the way

Breaking the sound barrier is prohibited over populated areas, but it does happen occasionally.

In 2012, a pilot in an F-16 from the Air Force’s elite Thunderbirds demonstration team accidently went supersonic while practicing over Tucson for the annual air show at Davis-Monthan, shattering windows around the city and causing more than $20,000 in damage.

In 2016, a sonic boom from an Air National Guard F-16 out of Tucson broke windows across the small Gila County town of Globe.

Some areas around Tucson could experience more sonic booms starting in 2024, when the Air Force plans to expand its use of Military Operations Areas spanning thousands of square miles of southeastern Arizona and western New Mexico.

Under a proposal now undergoing environmental review, the Air Force wants authorization for supersonic speeds down to 5,000 feet above the ground in operations areas that include Tombstone, Bisbee and Douglas and a huge swath of east-central Arizona.

Beck said she has been getting calls about mystery booms and seeing them turn up on local seismograph readings since she moved to Tucson and joined the UA in 1990.

She has even experienced a few of them herself, but “it was always hard to tell what they were,” she said. “It felt different than an earthquake, and I’ve felt many, many earthquakes.”

Tucson no stranger to seismology

The recent UA analysis by was made possible by a Panama-based company called Raspberry Shake and its new line of affordable seismographs for at-home earthquake enthusiasts.

“That didn’t exist more than a few years ago,” Beck said. Five Raspberry Shake devices are now in operation around Tucson, all of them installed within the past two years. Without the publicly available data from those citizen-science instruments, Beck said she and her team would not have been able to determine the direction and speed of the two booms from last month.

Tucson has a rich history in the world of seismology. According to Beck, the official seismic station here — hosted by the UA and operated by the U.S. Geological Survey — dates back to the 1920s, making it one of the oldest in the nation.

TUC, as the station is known, has recorded every major earthquake around the world over the past century or so, including Monday’s deadly quake in Turkey. It has also captured man-made explosions such as the Oklahoma City bombing in 1995 and the first nuclear detonation at the Trinity Site in central New Mexico on July 16, 1945. “That got recorded nicely in Tucson,” Beck said.

The station was originally housed at Udall Park, but the city eventually grew up around it and the site became “too noisy,” she said. In the 1960s, the instrument was moved to its present location in the foothills above Sabino High School and the Arizona National Golf Club, where it is anchored directly into the granite block of the Catalinas.

Security cameras belonging to Phil and Arty Williams recorded the sound of one of Tucson's "mystery booms" at their Picture Rocks home in 2019.

The station still recorded tremors on a rotating paper drum before about 1992, when it was upgraded to a fully digital set-up.

Investigating Tucson’s unexplained booms is something of a hobby for Beck and recent UA graduate Thomas Lee, both of whom have “two or three other jobs” they actually get paid to do, she said with a laugh.

But they plan to keep at it — and maybe even expand their inquiry in hopes of solving the mystery once and for all.

“It’s kind of an interesting phenomenon,” Beck said. “I’m interested in ground shaking,” and these booms are certainly powerful enough to shake the ground.

Star journalist shares memories of the 1985 Mexico City earthquake

1985 Mexico City earthquake

Updated

Debris from collapsed buildings blocks numerous streets in Mexico City on Sept 20, 1985 as a result of the 1985 Mexico City earthquake.

News of Tuesday's earthquake in central Mexico also marked the anniversary of the Sept. 19, 1985 quake that hit the nation’s capitol. It was a magnitude 8.1 temblor that killed some 10,000 people, injured many more and left countless people homeless.

A recent graduate from the University of Arizona journalism department, I had been at the Arizona Daily Star for about a month and was the newest member to the photo staff.

Information about the quake was slowly trickling in that morning when I received a call from photo editor Chuck Freestone, telling me I was going to Mexico City with reporter Keith Rosenblum.

At the office I was handed about $200 cash that I stuffed in my front pocket, and off we went to try to fly into Mexico City.

All commercial flights into Mexico were canceled. The only way to get to Mexico City from Tucson was to drive four hours to Hermosillo, Sonora and hope to catch a domestic flight.

In a roundabout way of stops at various Mexican cities, we were able to get aboard a plane to Mexico City, exchanging tickets on a tarmac just as the stairway onto the jet was being pushed away from the airliner.

Tent City along Paseo de la Reforma

Updated

Tent cities of the newly homeless line the streets and parks along the Paseo de la Reforma during the Sept. 20, 1985 Mexico City earthquake.

It was about 1 a.m. when we arrived and jumped into a taxi and proceeded to document the destruction. Towering buildings had become piles of smoldering rubble. Tents, some made from empty cardboard boxes, filled small parks and any open areas.

I had never seen so much destruction or despair.

Workers search through the rubble

Updated

Twisted metal and concrete get in the way of workers as they search for survivors of the Sept. 20, 1985 Mexico City earthquake.

Workers climb piles of rubble from collapsed buildings as they search for survivors of the Sept. 20, 1985 Mexico City earthquake.

At the same time, I witnessed so many people working for hours to help strangers. Dust-covered rescuers scrambled over huge slabs of concrete, twisted metal and broken glass in a frantic search for survivors.

Occasionally, work would come to a complete halt in the hopes of hearing any sound from survivors that would embolden the rescuers to work harder.

Toppled buildings

Updated

Workers use heavy equipment to move piles of rubble from collapsed buildings as they search for survivors of the Sept. 20, 1985 Mexico City earthquake.

Others provided food and drink to the new homeless. Their payback: tearful gratitude.

Fumbling around in the dark, I was pulling rolls of film, notepads and pens out of my pocket. The $200 stuffed in there too was lost.

Keith wrote his news story by hand. I wrote photo captions on pieces of torn notebook paper.

And it was people traveling back to Tucson that helped us share the story of the mass destruction with Arizona Daily Star readers.

Rescuers take a much needed break

Updated

Rescue workers take a break in their search for survivors of the Sept. 20, 1985 Mexico City earthquake.

Businessmen, vacationers and even nuns became our lifeline to Tucson, taking with them our stories and photos for the Star.

We eventually found a room on the 10th floor of the Hotel Galeria, overlooking the statue of El Angel de la Independencia near the Paseo de la Reforma, the wide avenue that cuts across the heart of the city.

In the early evening, as we took a short break in our room, an aftershock in the 8.0 range struck.

From our window, I could see The Angel sway, as did nearby buildings.

Trying to scramble off the 10th floor of a hotel during an earthquake is like trying to sprint on a rowboat.

We got to the stairway, and convinced about a dozen people waiting for the elevator to join us on the stairs instead. We made our way back to La Reforma and continued our reporting.

Major roadways blocked

Updated

Collapsed buildings spilled onto major roadways as a result of the Sept. 20, 1985 Mexico City earthquake.

What I saw over the next several days became the source of the nightmares that still haunt me.

Because of the overwhelming number of dead, a temporary morgue was established at a baseball field. People waited in a long line that led to right field to begin the grim task of looking for their missing loved ones.

What awaited them was a bizarre scene where a misty haze, caused by dry ice used to preserve the decaying bodies, drifted around the faces of the men, women and children of all ages who were laid side-by-side.

Off to the side was a Catholic priest who no sooner gave last rites to one person then he would quickly move to another as family members grieved over their loss.

My heart still goes out to people who endure the wrath of nature at its worst.

A difficult part of such an ordeal is that there is no one to blame or point an angry finger at. And there is no one to answer the question, why?

I do know there are journalists who will continue to be out there in the aftermath of disasters, searching for answers and telling the stories that will affect readers, listeners and viewers.

The few days I spent as a journalist in Mexico City during the 1985 earthquake brought me to the point of utter exhaustion and were some of the most memorable days of my journalistic life.

A. E. Araiza is lifelong Tucsonan and graduate of Pima College and the University of Arizona…