Earth’s ultimate disaster movie doesn’t come out for a few billion years, but some local astronomers are giving us a sneak peek.

A large team of scientists, including two from Tucson, captured the first direct evidence of an exoplanet being consumed as its dying star expands into a red giant.

The same process is expected to happen to our own sun in about 5 billion years, likely spelling the end for Mercury, Venus and possibly Earth.

Past observations have found the remnants of such planetary engulfments, but this is the first evidence that appears to show the process as it is happening.

The discovery was made using the Gemini South telescope in Chile, which is operated by the National Optical Infrared Astronomy Research Lab, or NOIRLab, a National Science Foundation institution headquartered in Tucson since 1959.

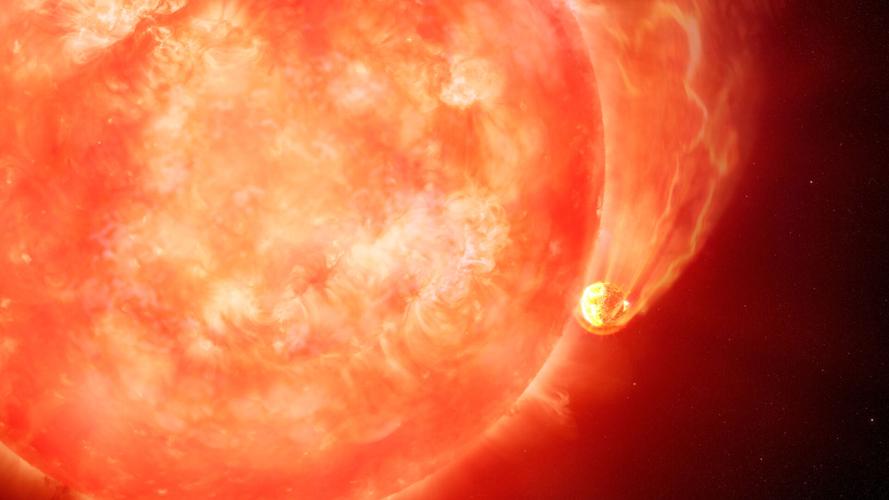

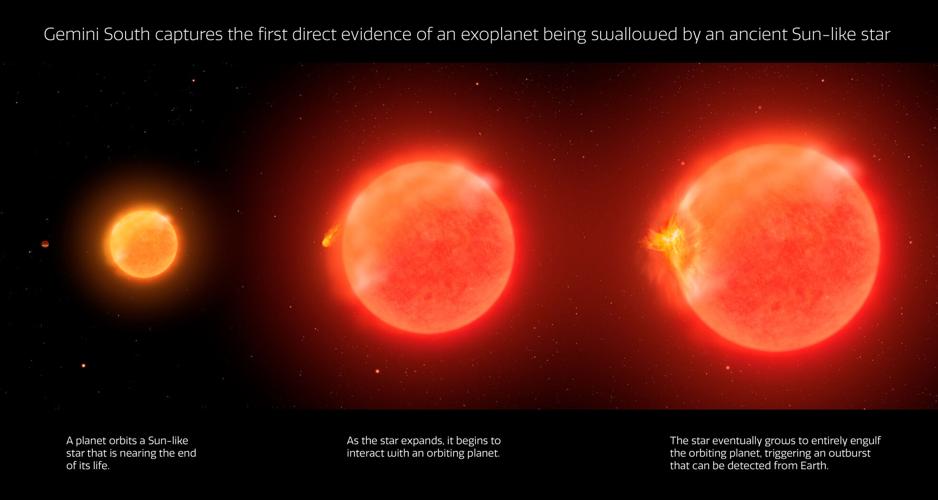

An artist rendering shows the process of a star like our sun expanding into a red giant as it exhausts the hydrogen in its core. Such a dying star can swell by as much as 1,000 times, exgulfing any nearby planets orbiting it.

When a star like the sun exhausts the hydrogen in its core near the end of its life, it can swell to as much as 1,000 times its original size. Any inner planets in the path of the expanding red giant are incinerated and consumed, releasing a burst of energy that can last for weeks.

Scientists believe they caught one of these outbursts from a dying star about 13,000 light-years away. The telltale signs of a planet skimming into oblivion along the star’s expanding surface were observed for approximately 100 days.

“I think there’s something pretty remarkable about these results that speaks to the transience of our existence,” said Ryan Lau, a NOIRLab astronomer in Tucson. “After the billions of years that span the lifetime of our solar system, our own end stages will likely conclude in a final flash that lasts only a few months.”

The findings were detailed Wednesday in the journal Nature. Kishalay De, an astronomer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, was lead author on the paper. Lau and fellow NOIRLab astronomer Aaron Meisner were co-authors, along with 24 other researchers, mostly from MIT, Caltech and the Harvard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

A team of astronomers, including two in Tucson, have recorded the first compelling evidence of a dying, sun-like star engulfing an exoplanet.

Based on the estimated number of stars and exoplanets in our Milky Way galaxy, such engulfment events probably happen a few times each year, but none have been observed until now.

The first hints of the planet’s destruction were spotted by the wide-field astronomical survey at Caltech’s Palomar Observatory in California. The event was confirmed using archival data from the Near-Earth Object Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer, of NEOWISE, a NASA space telescope that operated from 2013 to 2017.

The Gemini South telescope provided the high-resolution observations and long-term brightness measurements needed to distinguish the outburst from other solar events such as flares and coronal mass ejections.

“With these revolutionary new optical and infrared surveys, we are now witnessing such events happen in real time in our own Milky Way — a testament to our almost certain future as a planet,” De said.

Based on the characteristics of the energy outburst, researchers believe the star was roughly the same size as the sun before it expanded, while the planet it engulfed was at least the size of Jupiter.

The resulting explosion ejected about 33 times the Earth’s mass in hydrogen and about one third of the Earth’s mass in dust.

“That’s more star- and planet-forming material being recycled, or burped out, into the interstellar medium thanks to the star eating the planet,” Lau said.

Now that they know what they’re looking for, astronomers hope to identify similar events happening elsewhere in the cosmos.

“These observations provide a new perspective on finding and studying the billions of stars in our Milky Way that have already consumed their planets,” Lau said.

More fiery foreshadowing for what awaits our own solar system a few million millennia from now.