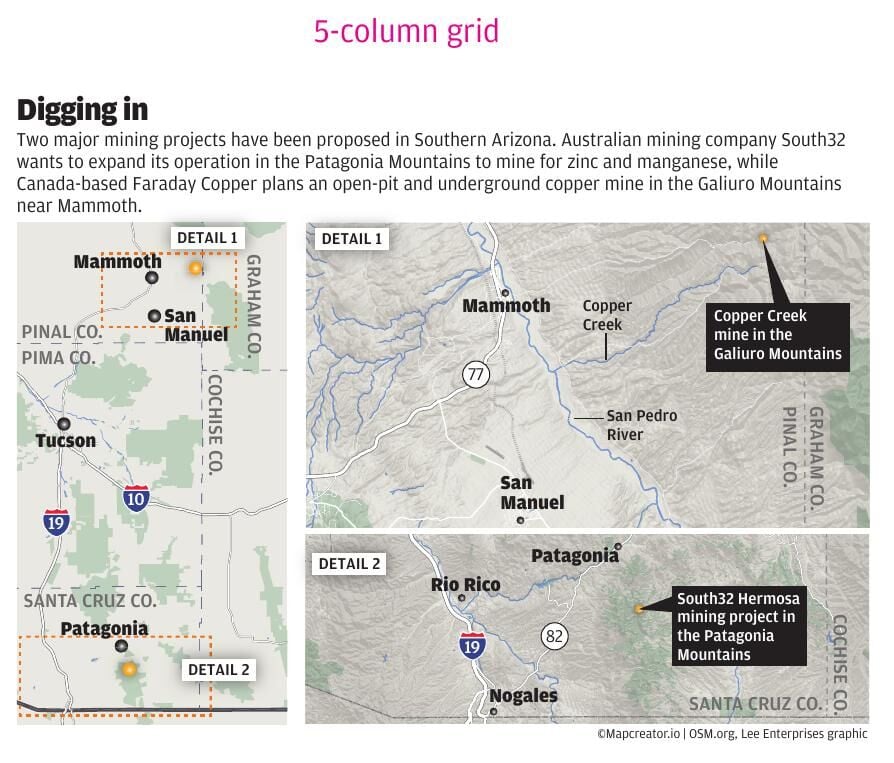

Southern Arizona could be on the cusp of a mining boom, with two major projects now in the works in mountain ranges east of Tucson.

Australian mining giant South32 wants to tunnel underground in the Patagonia Mountains near the U.S.-Mexico border in search of zinc and manganese, two critical minerals used to make electric vehicle batteries and other products for the growing clean-power economy.

On Monday, the proposed $1.7 billion Hermosa project became the first mine to be accepted into an Obama-era program aimed at streamlining the federal permitting process for what is considered critical infrastructure.

Meanwhile, in the Galiuro Mountains, about 100 miles to the north, Canada-based Faraday Copper is assembling property in hopes of developing an open-pit and underground copper mine in the steep hills 10 miles from Mammoth.

Faraday touts the site as “one of the largest undeveloped copper resources in North America,” with an estimated yield of 4.2 billion pounds of copper and a net value of $713 million.

Water flows down Copper Creek on March 31, not far from the site in the Galiuro Mountains where Canadian company Faraday Copper is proposing to build an open-pit and underground mine.

South32 officials say their Hermosa property is sitting on one of the world’s largest undeveloped zinc deposits, as well as what could be the only viable site in North America capable of producing battery-grade manganese from local ore.

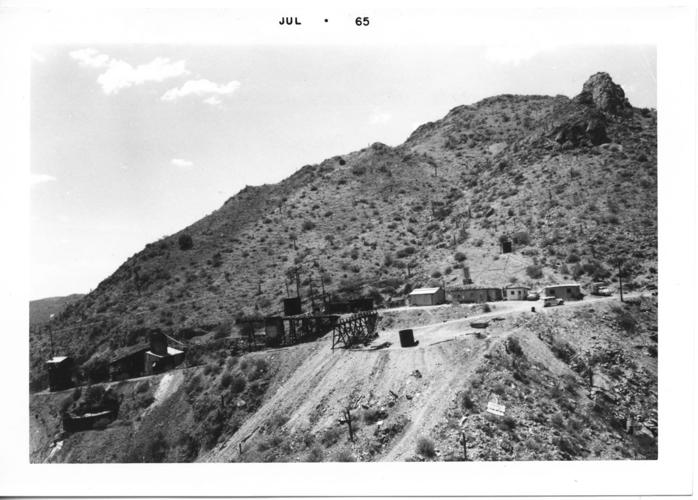

Both of the proposed mines are located in historic mining districts that date back to the 1800s, but neither site has seen significant activity for decades.

South32 spokeswoman Jenny Fiore-Magaña said the company is expected to make a final decision on whether to proceed with underground mining in the Patagonia Mountains later this year. If developed as planned, the project would represent the single largest investment in the history of Santa Cruz County.

The company acquired Hermosa in 2018 and began voluntary remediation at the site, about 9 miles southeast of the town of Patagonia, the following year to clean up historic mine waste left by a previous operator.

Fiore-Magaña said the initial mining work can be done without federal permits on the private land the company owns, but “full development of the project will require some activities that touch on surrounding federal lands and therefore require federal review.”

Hermosa hopes to obtain the permits it needs from the U.S. Forest Service and others in expedited fashion through its recent inclusion in FAST-41, a comprehensive federal infrastructure review program created by the bipartisan Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act signed into law by President Obama in 2015.

Uphill fight

South32 operates 11 mines on three continents and is the world’s largest producer of manganese ore. According to the company, there has been no manganese mining in the U.S. since the 1970s, leaving the country to rely on foreign sources for its entire supply of the mineral.

Both manganese and zinc are designated as critical minerals by the U.S. Geological Survey. President Biden has authorized an increase in domestic mining and processing of manganese and four other strategic minerals under the Defense Production Act to help strengthen the large-capacity battery supply chain.

“In some ways, it’s this crazy fight between critical habitat and critical minerals,” said Russ McSpadden, southwest conservation advocate for the Tucson-based Center for Biological Diversity.

According to McSpadden, the Patagonia Mountains are home to a number of rare and protected species that could be impacted by a major mining operation, including ocelot, Mexican spotted owl and Pima pineapple cactus.

The proposed Hermosa critical minerals mine could be built in the Patagonia Mountains within a mile of the historic World's Fair Mine, shown here in 1909.

The Hermosa mine also threatens to further fragment critical habitat for one of Southern Arizona’s most elusive residents. “We’ve fought for two decades to get the jaguar protected in the borderlands,” McSpadden said, only to see those protected areas gradually “picked apart” by developments like this one.

Even so, he said Southern Arizona’s two newest mining projects have largely been “flying under the radar” so far, as national environmental groups focus most of their attention on the Rosemont mine expansion in the Santa Rita Mountains south of Tucson and the Resolution Copper project at Oak Flat, east of Superior.

That has left local conservationists to challenge the projects.

Carolyn Shafer is president of the Patagonia Area Resource Alliance, a local nonprofit dedicated to preserving natural areas in and around their small town 60 miles southeast of Tucson.

The small band of volunteer activists has been battling plans to open a mine in the mountains above Patagonia for years. They worry about how the pollution, noise, dust, traffic and groundwater pumping associated with such a project will affect their community and the treasured wildlands surrounding it.

“The health and economic prosperity of our region are tied deeply to the well-being of the Patagonia Mountains and the Sonoita Creek watershed, which are the source of our drinking water, clean air and the biological wealth that drives our regional nature-based economy,” Shafer said.

If the Hermosa mine has to be built, she said, it must be done responsibly, transparently and with strict oversight to ensure its owner is held accountable in order to “avoid short-sighted destruction of natural resources in pursuit of corporate profits.”

But given the choice, Shafer would prefer to see nothing built at all.

“These mountains are no doubt filled with a lot of minerals, but these mountains are also filled with a lot of species” of wildlife, she said. “The first tenet of responsible mining should be that there are some places that should not be mined.”

Boom and bust

It’s unclear what sorts of federal reviews and permits the Copper Creek project might require.

A promotional video released by Faraday earlier this month depicts as many as six open pits at the site about 55 miles northeast of Tucson. The video also shows a massive, underground block-cave mining operation like the one that eventually caused a large sinkhole to develop next to the pit at the long-shuttered San Manuel copper mine.

A video by Canada-based Faraday Copper describes the planned excavation and potential value of a new open-pit and underground mining project in the Galiuro Mountains about 10 miles east of Mammoth.

In March, Faraday announced the purchase of a ranch surrounding its proposed project. The $10 million deal for the Mercer Ranch included 6,000 acres of private land and 32,000 acres of grazing allotments along the mine’s namesake creek in Pinal County.

The company said the Mercer family would continue to operate the ranch on the property.

In an online overview of the project, Faraday describes the area around Copper Creek as “politically-secure” with access to established mining infrastructure.

That sounds about right to environmental advocate Peter Else, who lives along the San Pedro River just outside Mammoth.

“Us grassroots conservationists are still in the minority,” he said.

Else worries about impacts to Copper Creek and the surrounding area from groundwater withdrawals, heavy equipment use and “endless truck traffic,” as ore is hauled away from the mine to be processed offsite.

A sign in the Galiuro Mountains on March 31 marks the location of recent drilling activity for the proposed Copper Creek open-pit and underground mine.

He said the project would also disrupt a migration corridor for wildlife moving between the Galiuros and the Catalinas by way of the Lower San Pedro Valley.

Ironically, one of the properties most likely to be impacted by the mine is a ranch along the San Pedro near Mammoth that was set aside for conservation mitigation as part of a 2014 land swap that gave Resolution Copper its controversial Oak Flat site.

Else said the old 7B Ranch and its 800-acre mesquite bosque lies downslope from the mine and downstream from the spot where Copper Creek empties into the San Pedro. As a result, land that was meant to offset the damage from one mining project could now be at risk from another mining project.

“These mitigation designations get degraded every time this happens. It’s just a really sad situation,” Else said. “How do you mitigate the impacts to dedicated mitigation land? I don’t think you can.”

But he also knows that plenty of his neighbors in their quiet corner of Pinal County would welcome a major new mine to the area, even if its benefits are temporary and its drawbacks might not be.

“Yeah, they’ll get an economic boost in Mammoth, but they’ll be left again when the mine plays out” or shuts down because of a dip in copper prices, he said. It’s a familiar cycle in Arizona mine country, where boom-and-bust communities sometimes end up with little more than a mess to clean up.

“This is a story that gets repeated time and time again in the Lower San Pedro Valley,” Else said. “It’s just a really sad situation.”