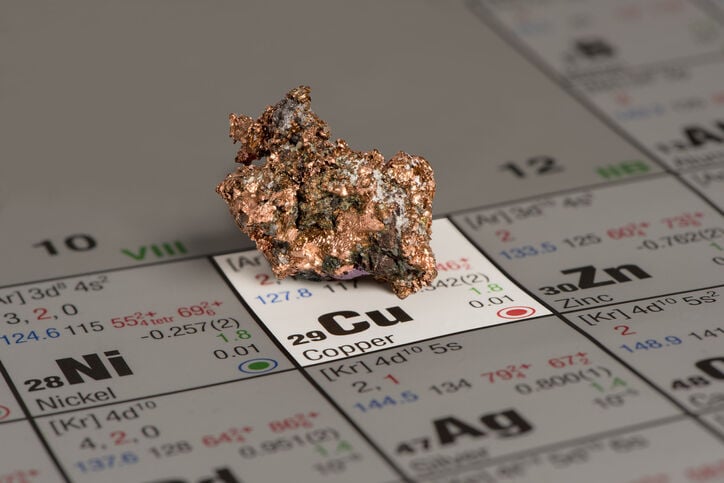

A new set of tax incentives is now available to copper companies across the U.S. because of a recent federal decision designating copper as a “critical material.”

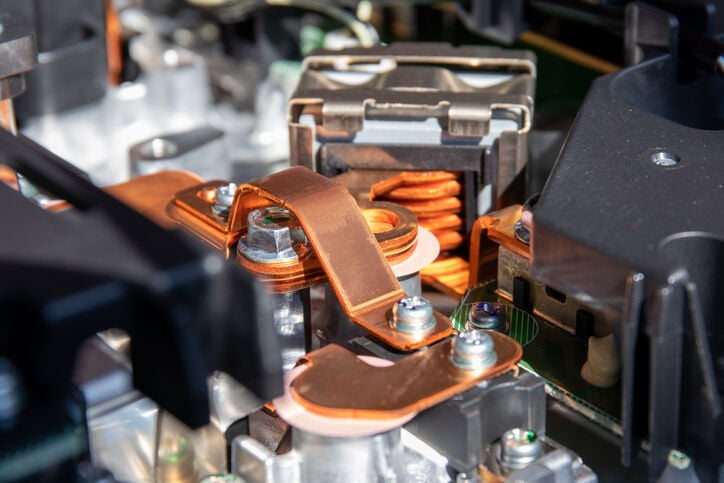

The U.S. Department of Energy gave copper that classification as a sign of its importance for future production of green energy projects such as electric vehicles and solar panels.

The U.S. decision will be a particularly major benefit to copper companies operating in Arizona. This state produces about 70% of all copper mined in the U.S.

Already, Hudbay Minerals has applied for tax credits available due to this designation, to help pay for construction of a copper concentrate leaching facility at its planned Copper World mining complex in the Santa Rita Mountains south of Tucson.

The National Mining Association, an industry trade and lobbying group, said it expects to see more companies seek such incentives. An association spokesman said he sees “considerable interest” in the industry to obtain them to encourage more green energy production.

Any project that qualifies for the credit can receive a credit of up to 30% of the investment that a company or other entity makes in a project.

The credits will go to projects that DOE finds will expand clean energy manufacturing and recycling and critical materials refining, processing and recycling, or will reduce greenhouse gas emissions at industrial facilities.

The DOE decision this summer did not come without controversy. A number of environmental groups opposed it, and a representative of one group, Earthworks, said it is “considering options” regarding a response to the decision, including possible litigation. Some tribal officials, including the San Carlos Apache tribe, also oppose it.

The issue underscores a broader dispute about the urgency of the need for copper as part of the U.S.’s green energy transition.

The dispute is over how great of a supply risk copper now faces at a time when demand for copper is expected to rise dramatically over the coming decades due to its usefulness for both green energy projects and more conventional forms of electric power transmission and distribution.

Today, while industry groups point to an ongoing shortfall in global supplies compared to demand, copper prices have been fairly volatile for several years. They’ve declined since about February, are higher than they were a year ago, lower than they were 18 months ago but significantly higher than they were two years ago.

None of the interest groups on either side of the issue disagree that copper is an essential element if the U.S. is to carry out the Biden administration’s goals of significantly boosting the use of renewable energy sources such as solar, wind and electrical energy in place of the burning of the fossil fuels coal, oil and natural gas.

Where the differences arise is over how to balance the supply risks for copper production — which are not likely to be severe at least in the short to medium term — with what everyone agreed will be increasing demand for it over the next 25 to 30 years.

Many experts agree, for instance, that the world needs to reach what’s known as a “net zero” goal of heat-trapping greenhouse gas emissions by 2050 to avoid the worst consequences of human-caused global warming and other forms of climate change. That goal has been formally set by the International Energy Agency, an intergovernmental organization that includes the U.S. government and that works to establish what it sees as a secure and sustainable global energy supply.

The disagreements are over what the U.S. government needs to do to get there with copper.

Other status rejected

The DOE’s decision came about three months after another federal agency, the U.S. Geological Survey, rejected a request from Arizona’s two U.S. senators, Democrat Mark Kelly and Independent Kyrsten Sinema, and a number of other senators and congress members to declare that copper is a critical mineral.

Such a designation would have qualified copper companies for additional tax incentives beyond those that will be available to them from the DOE’s critical materials decision. A critical mineral designation would also allow copper companies to seek fast-tracking for their federal permitting.

Another proposed Southern Arizona mine, the Hermosa project planned for the Patagonia Mountains near the U.S.-Mexico border, was approved this spring by the feds for fast-tracking. That’s because its owner, Australia-based South 32, proposes to extract zinc and manganese, which are on USGS’ critical minerals list.

U.S. availability of copper

The Department of Energy’s decision acknowledged that the risks to the availability of copper in the U.S. aren’t significant. But in a detailed assessment published over the summer, it noted that demand for copper is increasing significantly. Copper industry trade groups, meanwhile, say they expect global demand for copper will double by 2035.

DOE cites already increasing demand and predicted future demand increases for electric vehicles, an upgraded electricity grid, wind energy turbines and solar panels.

It said copper is “non-critical” in the short term, from 2020 through 2025, but moves up to “near-critical” in the medium term, from 2025 through 2035. That’s mainly due to expectations of increasing demand for copper for electrification purposes, including electric grid upgrades and electric vehicles.

“As our nation continues the transition to a clean energy economy, it is our responsibility to anticipate critical material supply chains needed to manufacture our most promising clean energy generation, transmission, storage, and end-use technologies, including solar panels, wind turbines, power electronics, lighting, and electric vehicles. Ultimately, identifying, and mitigating material criticality now will ensure that a clean energy future is possible for decades to come,” said Alejandro Moreno, acting assistant secretary for DOE’s Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, in a written statement.

Opponents of the designation, in their comments to DOE, hammered at what they see as a lack of real risk of copper supplies growing inadequate over the next 20 to 30 years.

“In Arizona copper is ubiquitous”

They also noted that the U.S. Energy Act of 2020 defines “critical material” as any non-fuel mineral, element, substance or material that the energy secretary determines has a high risk of supply chain disruption and is essential for one or more energy technologies. Using that language as a guidepost, they dismiss the need for defining copper as a critical material.

“Copper is not critical. In Arizona copper is ubiquitous,” Earthworks’ Mintzes said. “For that reason, there is little or no chance of supply chain disruption. Also, we recycle a lot of copper, usually through scrap metal, through manufactured products and semi-manufactured products.

“It’s robustly recycled. There’s a lot of it under the ground and a lot of it above the ground in the U.S. There’s also a lot of it around the world,” he said.

DOE didn’t respond over the past week to a question from the Star about why it considers copper a critical material despite the lack of supply risks.

But Andrew Kireta, president of the industry research and trade group the Copper Development Association, said DOE’s analysis reveals it’s not the current or near-term value of the copper supply risk that led to its critical material designation. It’s the direction of the supply risk that is beginning now, will grow over the next decade and will accelerate past 2030.

“DOE used a robust analysis of future demand scenarios against anticipated production capacity and signals that if something isn’t done today to strategically address this growing copper supply risk it likely will inhibit our ability to meet clean energy transition objectives,” Kireta said.

Ian Lange, a professor and researcher for the Payne Institute of Public Policy in Colorado, sees the demand-supply picture for copper as gray, while advocates on both sides see it as black or white.

“Copper is in the gray, because it has a lot of diverse suppliers. No, it would be in black for the supply demand imbalance. Rare earth minerals are fairly easily in the black — China has all of the refining capabilities for that.

“Copper has lots of suppliers; lots of smelters, that kind of pulls it into the gray,” said Lange, director of Payne’s energy and mineral economics program. “Presumably, it becomes a political consideration. The USGS definition of criticality is based on what it sees now, whereas DOE’s is for the next 15 years.

“Can USGS look at a gray thing and call it white and can DOE look at the gray thing and call it black? Of course. They have different time frames.”

Production in unfriendly nations

In an April letter to Sinema, explaining its decision to not designate copper as a critical mineral, USGS indeed took an entirely different tack from the DOE. The USGS typically re-evaluates its critical minerals list every three years and did it most recently in 2022. It has the legal authority to add or delete minerals in other years but declined to do that in this case.

First, it noted that imports of refined copper into the U.S. increased in 2021 but then decreased significantly in 2022.That indicates the 2021 import jump appeared to represent a rebound following a drop-off in 2020 as the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated.

In its analysis for the 2022 list, the survey concluded that copper had a relatively high economic vulnerability score, indicating the U.S. manufacturing sector is vulnerable to a supply disruption.

“But this vulnerability was mitigated by a relatively low U.S. net import reliance on foreign supplies and a diversity of foreign supply sources,” USGS Director David Applegate wrote to Sinema.

Although the U.S.’ reliance on copper imports increased from 2018 to 2021, the latest data from the 2023 Mineral Commodity Summaries, published on Jan. 31, 2023, indicate that import reliance fell from 44% in 2021 to 41% in 2022, Applegate wrote. The decrease happened even as U.S. copper demand rose, he wrote.

The U.S. has significant domestic copper production and a diversity of foreign supply sources, Applegate added. This country mined 1.3 million tons of copper in 2022 from seven states, including Arizona, he wrote.

“The United States has 25 operating copper mines, 2 smelters, 2 electrolytic refineries, and 14 electrowinning facilities,” he wrote.

And while many experts note that more than half of the global supply of refined copper is produced in the unfriendly nations of China, Russia, North Korea and Iran, refined copper imports into the U.S. aren’t dependent on those countries, he said. They come predominantly from Chile, Canada and Mexico, reliable trade partners with whom the U.S. has free trade agreements, he noted.

In explaining its decision to declare copper a critical material, the DOE said its methods for determining criticality are different from those of the USGS. USGS uses historical data on mineral demand and supply — in this case, from 2018 — to determine if a mineral is critical, in the broader context of economic and national security issues, DOE said. The energy agency, by contrast, is “forward looking,” DOE said. For instance, the agency relies on future demand trajectories and growth scenarios for various energy technologies, DOE said.

The environmental groups opposing designating copper as critical, however, told DOE in a letter that when USGS took a second look this year at the copper issue at Sinema and Kelly’s request, it also used data from a 2023 U.S.G.S mineral commodity survey that contains what the agency calls “the earliest comprehensive source of 2022 mineral production data in the world.”

While USGS’s 2022 designation relied on analysis from the years 2018 to 2021, as DOE points out in its assessment, USGS reconsidered the choice in light of data from the latest 2023 Mineral Commodities Summary and reached the same conclusion that the copper supply is stable.

Risks of supply shortages

Critics of the USGS decision, including those in the copper industry, agreed with DOE’s view. They said the survey relied too much on past data about copper availability that, in the Copper Development Association’s words, “does not address current and forward-looking policy demands that can leave domestic supply chains short of critical materials.”

“Continued supply trends and solid data confirm that the supply risk for copper is not a short-term issue that will self-correct without determined, immediate, and strategic action,” association director Kireta said. “We must ensure that America’s manufacturers and supply chains have ready, reliable, economic access to copper to meet the growing demand and policy goals for a cleaner electrical grid, a lower carbon economy, and a strong and resilient defense sector.”

Relying on short- or even medium-term copper supply forecasts assumes no major events like the global pandemic, or even significant delays to major copper delivery routes like the Panama Canal, Kireta told the Star.

“I wouldn’t categorize the size of that risk as small or insignificant. The data is clear that U.S. dependence on offshore sources for copper, including refined metal from both primary and secondary sources as well as semi-fabricated products, has risen steadily over the past decade or more. This import dependence is poised to continue to rise as our domestic supply picture remains stagnant or shrinks, as the DOE analysis shows.”

Mintzes, however, noted that the USGS left copper off its critical minerals not just last year but in its previous review in the late 2010s.

“The scientists looked at this twice, in the previous administration and current administration. It’s not a close call.”

This flyover shows the Santa Rita Mountains’ west slope, where Hudbay Minerals has been grading and land-clearing since April 2022 for its planned Copper World Mining Project. Video courtesy of Center for Biological Diversity.