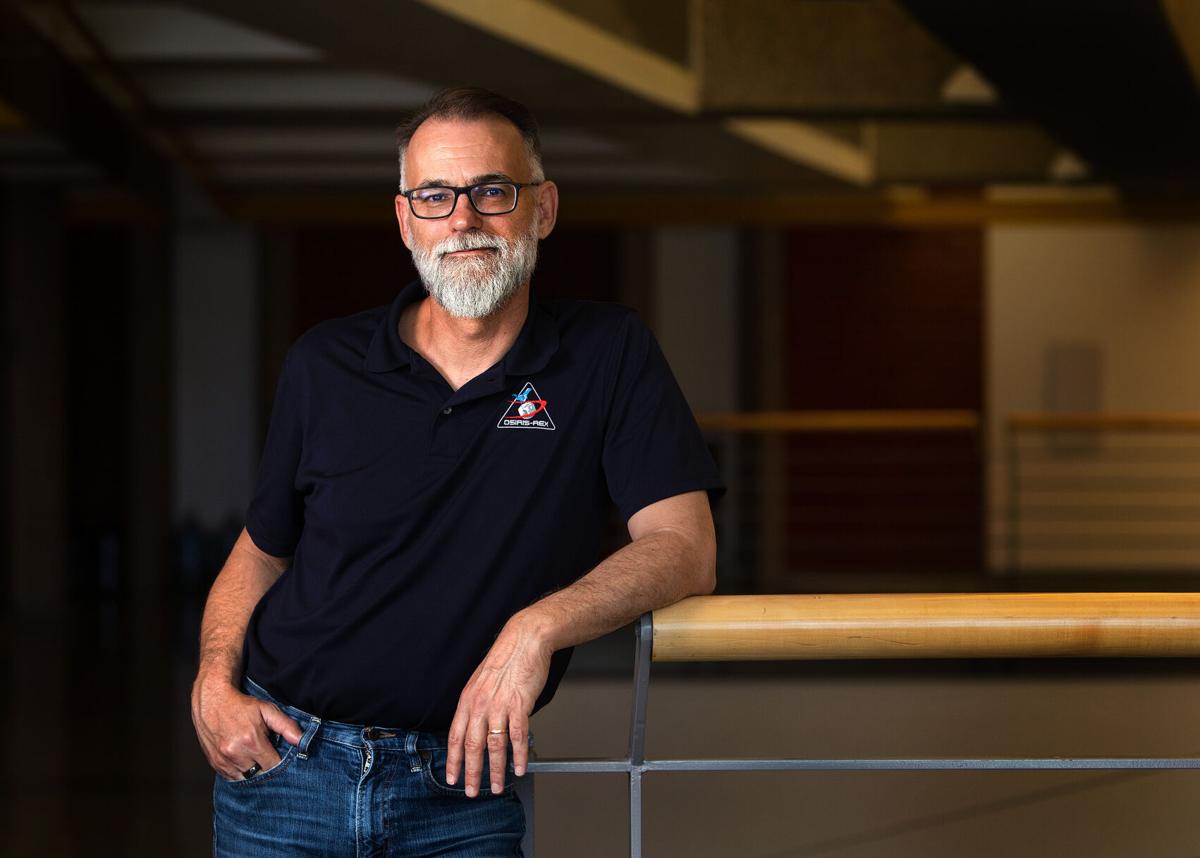

When OSIRIS-REx swings past Earth next week to drop off its priceless samples from asteroid Bennu, no one will be more relieved than Dante Lauretta.

The University of Arizona professor has been working on the NASA mission since 2004 and leading it as principal investigator since the death of his mentor and former boss, Michael Drake, in 2011.

Lauretta will be at the Department of Defense's Utah Test and Training Range, west of Salt Lake City, on Sept. 24 to help secure the newly arrived space capsule containing rocks and dust snatched from the surface of Bennu on Oct. 20, 2020.

The pristine asteroid samples are thought to contain clues about the origins of the solar system and maybe life on Earth. Their successful recovery will mark the end of a $1 billion, multi-billion-mile space voyage for which Lauretta has played a central role for almost 20 years.

Not bad for a kid who grew up without a television — or indoor plumbing, really — on a patch of desert north of Phoenix.

Lauretta was born on Oct. 19, 1970, in Montreal, with the dual citizenship to prove it, but he spent his formative years in a single-wide trailer at the end of a dirt road in New River, Arizona.

He went on to study math, physics and Japanese at the UA, where he now serves as a Regents' Professor at the prestigious Lunar and Planetary Laboratory.

The 52-year-old scientist is also a married father of two, who likes to unwind by playing guitar, doing yoga, designing award-winning board games and writing books. In July, he published a 3D atlas of Bennu with Brian May, a Ph.D. astrophysicist who also happens to be the lead guitarist for the rock band Queen.

Lauretta's next side project is a memoir of sorts, though he insists the coming book also serves as a biography for Drake, the spacecraft and its mission. “The Asteroid Hunter” is set for release on March 19, 2024, but it’s still missing one crucial chapter.

Lauretta plans to write the epilogue, titled “Homecoming,” in October, after OSIRIS-REx delivers its precious cargo.

He recently sat down with the Arizona Daily Star at his office at the UA for a wide-ranging chat about the long journey to Bennu and back, his background and how he's feeling as the mission’s last big test approaches.

(This conversation has been edited for length and clarity.)

Star: Describe what you and your team will be doing on Sept. 24.

Lauretta: I'm on the field recovery team, by choice. I really wanted to be out there. I've got to welcome this sample to Earth, right? I'm on the welcoming committee.

Star: So you’ll be standing by as the sample-return capsule comes down, and then you'll fly out to the landing site in a helicopter. How close will you land to the thing?

Lauretta: 250 feet. You don't want to have the helicopter blowing dust onto the capsule and all that stuff. Then it's (attached to) a 100-foot-long line in a harness when we remove it from the field, so the helicopter will never be within 100 feet of the capsule. It will fly the capsule in that harness back to the receiving area (where) other members of the team will physically pick it up and carry it inside of a portable cleanroom. Then we're going to start to disassemble it. The treasure box is what's called the science canister. It's like this aluminum housing that's got the sample head and the sample inside of it. All we care about is that canister that will get sealed up and flown to Houston the very next morning.

Star: Are you getting on the airplane with it?

Lauretta: Yeah, Monday morning (Sept. 25). That's the green-light schedule, everything going according to plan.

The thrilling finale of OSIRIS-REx, the University of Arizona-led NASA space mission, is set for Sept. 24, when a capsule containing rocks and dust from the asteroid Bennu is set to land at the Utah Test and Training Range, west of Salt Lake City.

Star: This will be on a military cargo plane, right? Have you flown on one of those before?

Lauretta: Yeah. When we shipped the spacecraft from Denver to Kennedy Space Center, we also used C-17. And then I was on an Antarctic Expedition way back 20 years ago, and we took a C-17 out of Antarctica.

Star: I wanted to ask you about that. I noticed you have an award on your wall from your work down there.

Lauretta: That's my medal. You get that medal from Congress if you spend more than 30 days in Antarctica in service to the United States. We were in the field for 42. The Antarctic Search for Meteorites.

Star: Why there?

Lauretta: Well, it's a big desert, so it's very dry. And meteorites, if they're exposed to water, they tend to rust and break down. And it's a natural conveyor belt. You've got these giant glaciers that cover most of the land out there. These meteorites from outer space land on the glacier, and the glacier kind of moves like a conveyor belt towards the ocean. But if it hits the mountains, the glacier tries to go over the mountains and the wind cuts it away, and you get this big concentration of meteorites right there. It's been collecting meteorites for a hundred thousand years for hundreds of miles up river of the glacier, and the glacier brings them all to you and drops them right at the base of the mountain. All you have to do then is drive around on the glacier looking for black rocks, and you'll find meteorites.

Star: So you were roaming around Antarctica in 2003, and then you joined the asteroid sampling mission?

Lauretta: That's right. About a year after I got back is when Mike (Drake) called me. He was my boss, he hired me. I was an assistant professor here, and he was the lab director. And we got along really well, you know, we kind of hit it off. We had similar research interests. We went to the same conferences. He was my mentor, even before OSIRIS-REx.

Star: Why do you think he picked you as his deputy P.I. for the mission?

Lauretta: Well, I don’t like to get inside other people's heads. But I was doing a lot of astrobiology work, origin of life work, and getting some really exciting results in the lab. Mike studied planet differentiation (and) core formation. But he knew for this mission we needed to go (with the) origin of life, that's what was going to sell it to the agency. So he brought me on as that scientist to really talk to him about that.

He came on board because of his management experience, leading a big lab and being involved in these other missions. He was seen as a leader. It made sense for him to lead a program. He was 25 years older than me, so he was in his late 50s, which is normally when you take on one of these jobs.

Arrival anxiety

Star: Is there a part of this last stage of the mission that worries you the most?

Lauretta: Yes, the final performance of the sample-return capsule. Because it's been quiet, and the batteries have been off since we launched (in 2016), so we haven't talked to any of that. And I know it's all been tested, and it's all going to work. But there are batteries that we're not going to hear from until a couple hours before we hit the top of the atmosphere, and those release the parachute.

A training model of the OSIRIS-REx sample-return capsule is seen during a drop test on Aug. 30 at the Department of Defense's Utah Test and Training Range. The real capsule is due to land in Utah on Sept. 24.

We've been through countless reviews and exercises and tests about what's going to happen in the days leading up to the SRC release. We've just talked about it so much. And we've reviewed the footage from the Genesis capsule: the 2004 Lockheed Martin-built sample-return capsule that crashed because the parachute didn't deploy. I close my eyes, and I see that capsule crashing into the Utah mud.

I just want our sample safe on the ground on Earth, right? That moment, I'm carrying so much anxiety about it. It just feels like that's going to be a watershed moment in my life.

Star: And all that starts with the parachute?

Lauretta: Yes, I think if I see the chute open, we're good. We're good.

Star: It's going to land somewhere.

Lauretta: It’s going to land somewhere, that’s right. And we’ve got the Air Force watching it. They're gonna know exactly where it is.

Star: So what happens before all that?

Lauretta: We have to make a go, no go decision. It's possible we will not release the capsule. That's part of our decision matrix.

For example, if something goes wrong with the spacecraft and the capsule is coming (down) right in the middle of Salt Lake City, we can't release it, obviously, because people might be at risk of injury or fatality. Safety is number one. It would take a lot of things to go wrong for us to drift. But, you know, we're coming in from outer space, and you're talking like 80 miles (between the designated landing zone and Salt Lake City), so it could happen. If we're off course, we’ll just zip by the Earth and that sample leaves.

So the go, no go poll, that's at 2 a.m. on Sept. 24. That's critical, because then it's like, “OK, we're good.”

Then the spacecraft has to receive the command from the control center in Denver to release the capsule, and then those batteries get turned on and we see if they're alive. We'll know at that point if we're coming in with a live capsule or a dead capsule.

We'll release (even) if those batteries are dead and just get ready for this Genesis level event, as we call it — just get ready for a hard landing and to go out there and see what we can find.

Star: What happened when the Genesis capsule crashed? Did it just disintegrate?

Lauretta: It was a solar wind collection mission, so it had these really big plates of high purity material — silicone like a computer chip would be built on or gold — and those fragmented and shattered. They were still able to find pieces of them and actually recover the science, but it was a heartbreaking and painful process. We don't know what our science would be like, because we have a very different kind of sample. We have this probably powdery asteroid regolith.

Origin story

Star: You probably get asked to explain this mission all the time. What's your response when someone says, tell me about OSIRIS-REx?

Lauretta: Well, we built a robot to go to an asteroid to get dirt and rocks and bring it back to Earth. And the question is, why would you go do something like that? The reason we're interested in our specific asteroid named Bennu is really two-fold. The first is what I'm really interested in: the origins investigation. I'm interested in the origin of life, the origin of the solar system and the origin of Earth, specifically as a habitable planet. Bennu is an ancient remnant from the beginning of the solar system. It's four and a half billion years old. It formed before the Earth did, and it records the earliest chemistry of carbon and water and the kinds of things that were delivered to the Earth by objects like Bennu in our ancient past. So it gets to that question we all ask ourselves: Where did we come from?

The second reason is Bennu is a near-Earth asteroid that's considered potentially hazardous. It might impact the Earth about 160 years from now in the year 2182. So the OSIRIS-REx mission gives humanity the information it needs in the event that this asteroid, or really any asteroid in the future, is going to come and impact the Earth. All of the technology, going out to the asteroid and characterizing its orbit, its chemistry, its geology, its rotation — that will help you with a future mission where you might need to prevent the asteroid from hitting the Earth.

Star: So you're learning what you need to know to launch a planetary defense mission one day?

Lauretta: Exactly. And you’re also really refining the odds of whether this particular asteroid is going to hit the Earth or not.

Star: You’ve got a pretty solid sense of that at this point, right?

Lauretta: It's a .05% chance in the next 200 years, which is low. I like to say you’d cross the street with those odds.

Star: Help us visualize the amount of asteroid material you think the spacecraft is bringing back.

Lauretta, grabbing a plastic foam coffee cup from his desk: Like eight ounces, right? So it should be like a coffee cup full. This is probably an eight-ounce cup. And it depends on the density. If it's really low density, it'll be over-filling the cup. If it's high density, it will pack down in there.

Star: And that doesn't count any bits that might be clinging to the container inside the return-capsule.

Dante Lauretta, left, poses with his mentor and OSIRIS-REx predecessor, University of Arizona professor Michael Drake, in 2007. Drake died in 2011, six months after NASA awarded the asteroid sampling mission to his UA team.

Lauretta: That's right. I think there'll be dust covering everything inside the canister.

Star: That’s one of the few problems you've run into with the mission so far, right? You ended up stirring up so much asteroid debris that it was leaking from your sampling device.

Lauretta: That's right, and we lost (some) sample (material) because of that.

Star: And that happened because Bennu didn’t behave the way you expected it to?

Lauretta: Yeah. Every time we've tried to interact with a planetary surface for the first time, we've been surprised. We knew something would happen. We were ready to be surprised, which is kind of the best you can hope for in those situations.

Formative years

Star: Tell us about your childhood.

Lauretta: I moved to the States pretty quickly after being born in Canada, then moved around quite a bit and landed in Arizona in 1975. New River was like fourth grade through freshman year of high school, so kind of the formative years.

Star: That's when you were living in the mobile home?

Lauretta: In the middle of nowhere. I went to Deer Valley Middle School and Deer Valley High School. It was like an hour each way. We were out at Carefree Highway and 16th Street, and there was nothing out there. We didn't have plumbing. We had to go haul our water. We had this big 500-gallon tank that we had to drive to a filling station whenever it ran out, get 500 more gallons and bring it back.

Star: Wow.

Lauretta: It's crazy to think about. We didn't have a TV. Books and school was kind of it for outside information. I had a job starting at 11 years old. I was a stable boy basically, cleaning out horse stables at a local Arabian show-horse ranch. I got a job there, and I saved $60, and I bought a 13-inch black-and-white cathode-ray-tube TV so I could see what was going on in the world.

Star: Did you ever get yourself in trouble out there?

Lauretta: Lots. Yes. Sure. I can't imagine my kids doing the stuff I was doing at age 11, 12, 13. We would go miles out into the desert, me and one other buddy. We would explore mines, we would go jump off cliffs into swimming holes. We were stupid kids.

Star: So how do you go from stable boy to astrophysicist?

Lauretta: Well, I did well in school, and I got a scholarship to go to the University of Arizona. I came here as a math major, theoretical math, partly because I had no clue what it meant to pick a major. I was the first person to go to college in my family, and I was like, “Well, I'm pretty good at math. Let's do that.” And I also figured that if you learn your math, you can do a lot of different things with it, so I expanded into physics.

Then in my last year in college, I got a Space Grant from NASA to work as an undergraduate researcher, and that really opened my eyes to this whole field of planetary science. That is kind of where I got the spark and decided, all right, I want to get in on this.

And it was an interesting time. It was the early 1990s, and NASA's planetary science program had kind of been in the toilet for most of the ‘80s. It was all (space) shuttle, and there were no new missions being funded. But in the early ‘90s, the Mars exploration started to come back online, and I thought I was gonna get involved in that.

Star: It didn't quite work out that way, though.

Lauretta: Yeah. I started on the Mars Observer spacecraft. That's what I went to graduate school to work on. And that spacecraft was lost within months of my arrival (in 1993). The spacecraft disappeared, the mission was over, no data was returned. I'd been working a full two months on the program, so I was like, “Well, now I gotta go figure out something else.” But my professors and mentors had been working (on it) for decades.

Star: So I guess that's another thing that you carry with you, right? You've seen what happens …

Lauretta: when these missions fail. That's right. Careers can be over.

Star: And right at the goal line.

Lauretta: Just like we’re facing (now).

Star: So it all started with that NASA Space Grant. Is that the one you learned about from an ad in the Daily Wildcat (student newspaper)?

Lauretta: Yeah. I just casually reading it, and it kind of showed up there. I just got off my shift as a breakfast cook (at Mike’s Place). I had lots of jobs back then. I was in college, so I was paying the bills with whatever would do that. I worked at the loading dock at a department store. That was kind of fun. I worked at a game store, because I always loved board games. Lots of restaurants, lots of tutoring jobs around campus. I worked for athletics and tutored the student-athletes. I did math, physics and philosophy for the student-athletes, which was fun. I was really into philosophy, almost majored in philosophy, but I figured that's the kind of thing you can do while studying math.

I still am interested in philosophical issues. The search for life in the universe, the origin of life and all these things that we're going after — you start poking at the boundaries where science breaks down, which is where the really, really fun stuff is.

Star: How do you mean?

Lauretta: There's certain things we can't explain in the scientific paradigm right now, consciousness being a big one. We can't explain why we are conscious, where our mind comes from, the origin of mind. I kind of break it up into four fundamental questions, and science is doing OK on maybe two of them, one better than the other: The origin of the universe; the origin of the solar system, including our planet; the origin of life and the origin of mind.

The origin of the universe, we really don't know what's going on there. Once you get past the cosmic microwave background radiation and you get to the Big Bang, science kind of loses it, right? We can't explain how that happened. We just say it looks like it did happen.

The origin of the solar system we’ve made a ton of progress on. That's kind of where I grew up, my field, and I think we've got a pretty good sense that physics and chemistry is really taking us almost all the way there, if not all the way there.

The origin of life is still a huge mystery. We don't really know how you go from inanimate matter to living material. What is the key distinction there, and how could the origin of life have taken place? Physics and chemistry has done a lot to help us understand biology and biochemistry for sure.

And then the origin of mind? Wide open. No idea why. Science just doesn't explain it. There's nothing in physics and chemistry — or I’d say very little, and none of it’s widely accepted — about where the conscious experience comes from. We’re working on it.

"You're the guy"

Star: What has been the most stressful part of the OSIRIS-REx mission for you?

Lauretta: Honestly, the most nerve-wracking time period was very early in the mission, when we were still in the proposal phase. Mike Drake, who was my mentor and the P.I. (principal investigator), was really sick, and I had to step up and lead. Then Mike would come back and be healthy for a while, and I would step aside. So I was really worried about him, and everything was on the line. Like if you don't win that phase, you're done. You don't fly.

So it was really those early days. First of all, just being there with Mike, somebody I cared about who was dying, was very stressful. And also because without Mike, I was the one that had to do it, right? I was pretty young; I was in my 30s. I was like, “I don't know if I'm ready for this job.”

Star: There must have been some people, maybe even involved with the mission, who were thinking the same thing.

Lauretta: Exactly. There was a lot of doubt about my ability to come in and lead the charge. And there was part of me that was like, “Well, maybe I should listen to them.” But the other part of me was like, “You can do it.” And Mike, you know, we had this moment at the end, where he really passed the torch. He was in the hospital, right before his last procedure, and he said, “You’ve got to take it. You’ve got to go. You're the guy.”

Star: So how do you decompress from a high-stakes job like yours? What do you do to relax — or at least look relaxed?

Lauretta: I think side projects. You know, we’ve got the Bennu book (with Brian May), and I have another book that's coming out. I try to be creative. I'm a board game designer, so I've designed games. And I love playing board games, especially with my kids and other family members.

In the mornings, the first thing I do when I wake up is usually a workout — yoga or strength training or maybe a hike. And I play my guitar. Not well, but, you know, that’s not what it's there for. It's there for stress and to go on my back patio and howl with the coyotes or whatever.

Star: And now you’ve written a memoir. Except the final chapter of OSIRIS-REx is not in the book.

Lauretta: It's to come. The epilogue is not written. Right now it ends in May of 2021, when we depart Bennu. That's the last paragraph. So the agreement was we would get this into production and get everything copy-edited and typeset, and then I would deliver the final chapter a month after the capsule is on the ground.

Star: You’ve certainly got a good story to tell.

Lauretta: It's not just about me. That's the fun part. “The Asteroid Hunter” is actually OSIRIS-REx. I didn't know that when I started writing it, but as the book unfolded, its OSIRIS REx that turns out to be the hunter.

Star: So it’s OSIRIS-REx’s memoir.

Lauretta: Basically, yeah, and I'm involved. But OSIRIS-REx, obviously, is a big part of my life.

Star: Nearly 20 years. That’s almost a career. It’s close to a generation.

Lauretta: Exactly. And I'm in my early 50s, so I still have some runway ahead of me, hopefully.

Star: Now the real work begins.

Lauretta: That's right. The whole mission was about the laboratory science, which is why I signed up for it in the first place. That was the deal.

Star: Speaking of books, tell us more about your recent collaboration with Brian May.

Lauretta, pulling out a copy of the new atlas: So this is “Bennu 3-D: Anatomy of an Asteroid,” which we just published as a joint venture between the University of Arizona Press and the London Stereoscopic Company. And the London Stereoscopic Company is owned by Dr. Brian May — or Sir Brian May, I should say — who is a science team member, actually. He's been working with us really since 2018, and he became an integral part of the team because of what he does.

University of Arizona professor Dante Lauretta, right, poses with Brian May, lead guitarist for the rock band Queen, in 2019. Lauretta teamed up with May, who holds a doctorate in astrophysics, on a new book about the asteroid Bennu.

He calls it Victorian-era science. He has these stereoscopes, like this one here, and he finds two images that make a perfect stereo pair. Then when you look at them through the stereoscope, the scene pops up in beautiful 3D.

He started doing this with just the images we were putting out publicly on the internet, and he sent them to me kind of out of the blue. I thought I was being punked, like there's no way this is really Brian May emailing me. But sure enough, it was him. And when I saw the product, I was like, “We could really use these for site selection. Can you make more of these?”

He was thrilled to be part of the team and to be contributing in a productive way to our sample site selection. He and his partner, Claudia Manzoni, who does a lot of the early recon work to find the data, did like 50 different regions of the asteroid surface for us as we were hunting for our sample site, and they produced some amazing and beautiful products. At the end, we kind of looked at the body of work, and we were like, “We should just put all this in a book.”

Star: The book even comes with a stereoscope.

Lauretta: Yeah, that's right in the back. You can just wander around Bennu forever and look at the amazing 3D shots of it. That wow moment, Brian loves that. And of course, Brian was a hero. I loved his music as a kid growing up. It was just super cool to be working with one of your heroes. And he's a really nice guy. He loves the science and the mission, and he knows his stuff. He's got a PhD. So we had a ton of fun.

Star: Did you get to jam with him at all?

Lauretta: A little bit, just talking about a song that I was working on that he thought was interesting. He gave me some things to go do, which I need to go do. We'll see if we move it forward or not. It could just be a lark.

Star: Wow.

Lauretta: Yeah.

Star: You and Sir Brian have something else in common. You both have asteroids named after you. Do you guys ever compare notes?

Lauretta: We do. You always do. In the asteroid-named community, the lower the number, the more prestigious it is. So mine is 5819. I forget what his is, but mine is lower.

Star: That's great. You’ve got something on Brian May.

Lauretta: We're actually pretty good admirers of each other's work, I think. And we share an attention to detail. That's a trait that we came across with the book. Every little thing was scrutinized at a very high level. His work, especially his music, is known for very high production quality, very fine attention to detail, and that's how we approach our science.

Star: And as it turned out, you needed his 3D imagery.

Lauretta: That's right. We needed it for our site selection process. Brian sent a whole case of these (stereoscopes) to the sample site selection board. It works with your phone, so we could just keep swiping — site one, site two, site three — and get a real good sense of the challenge that was facing us.

Star: Another surprise Bennu sprung on you.

Dante Lauretta, left, a UA professor and leader of NASA’s OSIRIS-REx asteroid sample return mission, reacts after the spacecraft touched down on Bennu on Oct. 20, 2020.

Lauretta: Exactly. It was very rough and rugged and much more rocky than we had anticipated. We had to improve our guidance accuracy enormously.

Bottomless cup

Star: How many people are on the OSIRIS-REx team these days?

Lauretta: So direct employees here at the University of Arizona, we're at about 35. Then we have our partners at NASA, and we have our partners at Lockheed Martin. There's about 250 people full time on the mission right now. And when I look at my extended sample analysis team, there's another couple hundred (at) laboratories around the world that are getting ready to receive samples.

Star: Is anybody else going to have a lab as nice as the one you’ve built here?

Lauretta: (Laughs) No, we're going to have the best. There's lots of really great laboratories on the team. I don't want to sell my collaborators short. But we have an amazing facility here. We're going to do cutting edge research.

Star: And for a long time to come, right?

Lauretta: The rest of our lives and our students’ lives. The great thing about sample return is that it just keeps on giving. We're reasonably smart, we've got these great new instruments, we're going to tackle all these big questions. But the people in the future, they're going to be even smarter, they're going to have even better instruments, they're going to know everything we know, and they can design whole new experiments.

I think I'll be involved in Bennu sample science for the rest of my life. And I'm training a bunch of students, and they'll continue to study this.

Star: That coffee cup full of material is going to go a long way.

Lauretta: It's an infinite supply for us. We work at the atomic scale. So when you start counting atoms, there are a lot of atoms in this material.

Star: So what's going through your mind right now as the mission approaches the finish line?

Lauretta: This is a pivot point for me in life in many different ways. But not being responsible for a spacecraft and a NASA mission, especially the flight part of it, that to me is going to be a huge relief. I can just feel this weight getting heavier every day, and I know it’s going to be lifted. I'm really looking forward to that change, that transition point where I can go back to being a professor and teaching and working with my students and working in the lab and enjoying the results of these missions without the burden of the leadership.

Star: How does that burden manifest itself?

Lauretta: My job is to be the one that's looking across all the elements of the project and making sure everybody who needs to be communicating is communicating. I'm always planning the next phase, right? My team implements what's happening today on the spacecraft. I'm the one that looks forward.

This is your life: Dealing with the budget, what happens when Congress shuts down the government, all these crazy things you need to be aware of as P.I. but you don't think about as a scientist. The P.I. shields the team from all of the nonsense as much as possible — just deals with it and says, “I don't want this falling on my team's head. I'm gonna make sure it stays up and out.”

Star: That’s right, you’ve had to live through a couple of government shutdowns. What does that mean for a mission like this?

Lauretta: Well, it means your civil servants don't get to go to work. In development, it's really hard. You're trying to build hardware and make a launch date, and you have a third of your workforce say, “Literally it is illegal for me to answer this email.” It's like, what is the use of this? There's no problem that's fixed with what you guys (in Congress) are doing there.

You just spend your way out of it. It costs you a lot of money. For every dollar you defer, it costs you $3 to make it up. There's nothing more annoying than when a politician exclaims with glee how much money they're saving by shutting down the government, because they're actually spending three times what you normally would have spent if you kept the government up and running. All of that work still has to get done.

Star: Do you remember your first shutdown?

Lauretta: 2013. That was during development, before launch, building our instruments. One of our instruments was at (NASA’s) Goddard (Space Center), and that was the team that really got hit the hardest.

Star: How about your second shutdown?

Lauretta: The second one was 2018, I think. We were in operations, and that was a little easier to deal with. We got an exception for our people operating the spacecraft, because it was considered a national asset that needed to be protected. You’ve got to keep flying the spacecraft.

Then the other thing is, a lot of us are (government) contractors, so we make sure our contracts are funded so the contractors can keep working. It's just the civil servants that get shutdown, so you plan for it. We're even planning for it now. We think there might be a government shutdown in October, so we’ve got to get the (asteroid) sample out of Houston before Sept. 30 or else, you know, our team in Houston could be out of work and we won't get access to our return sample until they're back.

Star: So the looking-ahead part involves things most researchers never have to worry about.

Lauretta: That’s right. I follow Politico.com and The Hill and all those stupid websites that tell you what the politics are. I was always looking at the president's budget, because that gives you the five-year outlook. Congress funds one year at a time, but the president submits a five-year plan. Whether that is going to get implemented into law you have no idea, but it's the only document you have that shows you what the next five years might look like.

I have a whole lecture on that when I teach a class on how you lead a spacecraft mission. There's a whole lecture on the federal budget process and how you get your project into the federal budget.

Star: Yet another reason to look forward to the return of the asteroid samples and the end of the mission: No more bureaucracy to deal with.

Lauretta: I can be a scientist again.