It was a lofty goal, but a University of Arizona-led team has achieved it with GUSTO.

A cosmic mission in Antarctica led by U of A astronomer Christopher Walker just set a new NASA record for the longest scientific balloon flight.

The team launched its massive helium balloon on Dec. 30, and the high-altitude observatory has been floating above the southern continent ever since, collecting infrared data about the lifecycle of stars in our galaxy and beyond.

At 10:22 a.m. Saturday Tucson time, the mission known as GUSTO — mercifully short for Galactic/Extragalactic ULDB Spectroscopic Terahertz Observatory — broke NASA’s previous record for the longest heavy-lift scientific balloon flight: a mark of 55 days, 1 hour and 34 minutes set in 2012, also in Antarctica.

“GUSTO has proven that balloons can be used to do really groundbreaking science, not just for a few days, but over weeks and weeks of time,” said Walker, who is principal investigator for the mission and has worked on telescope projects in Antarctica since 1994.

He and his team from the U of A’s Steward Observatory worked with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory and other partners to provide the telescope and instrumentation for GUSTO.

The observatory is studying the cosmic gas and dust between stars that gives birth to new stars and galaxies.

“We were all part of the interstellar medium — every atom and molecule in your body was at some point gas and dust flowing between the stars,” Walker said.

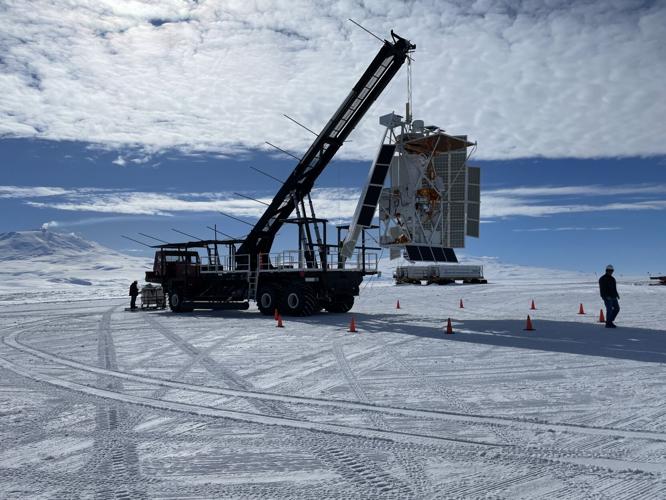

A crane holds a telescope designed and built by a team from the University of Arizona before it was launched on a high-altitude balloon over Antarctica on Dec. 30. On Saturday, the ongoing balloon flight set the NASA record for the longest mission of its kind.

GUSTO is designed to map the distribution of carbon, oxygen and nitrogen in the Milky Way and the neighboring Large Magellanic Cloud to produce the first complete spectroscopic study of every phase in the birth and evolution of stars.

During its flight, the zero-pressure scientific balloon expands to the size of a stadium and reaches altitudes of more than 125,000 feet. That allows the 4,800-pound, SUV-sized telescope suspended beneath it to detect faint terahertz signals from space at frequencies up to a million times higher than what comes out of an FM radio.

The signals are easily absorbed by water vapor in Earth’s atmosphere, so detecting them with a ground-based telescope is nearly impossible. By using a balloon, scientists can collect the elusive data at a fraction of the cost of a fully space-based telescope.

Walker’s team first proposed the mission in 2014, and NASA selected the project in 2017.

GUSTO was launched into a clear blue sky at 11:30 p.m. Tucson time on Dec. 30 from NASA’s Long Duration Balloon Camp near McMurdo Station, 850 miles from the South Pole.

Andrew Hamilton is acting chief of NASA’s Balloon Program Office at the agency’s Wallops Flight Facility in Virginia.

He said the balloon has performed “beautifully,” with no signs of degradation. GUSTO could keep flying — and extending its record — for weeks to come, so long as atmospheric conditions remain favorable.

“The health of the balloon and the stratospheric winds are both contributing to the success of the mission so far,” Hamilton said in a news release.

The flight has no set ending date.

To test the durability of the technology, NASA will let the balloon keep riding the circular wind currents of the Southern Hemisphere summer for as long as it can, even if it strays beyond Antarctica or comes down where it can’t be retrieved.

GUSTO’s onboard liquid helium tank is expected to run out sometime in March, and cooling temperatures above the South Pole will eventually cause the balloon to sink, as constant sunlight gradually gives way to the return of night.

Walker won’t have to worry about the changing of the seasons for his next research proposal: He wants to trade the balloon for a rocket to send his terahertz telescope into space.