Editor's note: This is the last of six stories for "Colorado River reckoning: Not enough water," an investigative series by the Arizona Daily Star that observes, at length, the future of the Colorado River.

Something's got to give.

As Colorado River water grows increasingly scarce over the next 30 years, we in the Southwest could be using as little water every day as drought-stricken Sydney, Australia, uses today.

Even in 5 to 10 years, we're likely to pay 60% more than now to bring Central Arizona Project water from the river to Tucson.

Food prices are likely to be higher and crop production lower in the Southwest.

City residents will keep installing more efficient toilets, faucets, shower heads and other indoor plumbing fixtures, while lawns will be increasingly scarce across the region.

Small power boats head upstream on the Colorado River just below Glen Canyon Dam. In 5 to 10 years, we're likely to pay 60% more than now to bring Central Arizona Project water from the Colorado River to Tucson.

The practice often disparaged as "toilet to tap" — treating wastewater to drink — is likely to become commonplace as cities hunt for new water sources.

Cisterns that have increasingly popped up in Tucson yards to catch rainwater will become a common sight across the West.

And we will have to be very careful about not replacing lost river water with pumped groundwater, which would trigger the drying of more wells, ground collapse from land subsidence, and earth fissuring.

These and other forecasts and cautionary notes about the long-term impacts of Colorado River water cutbacks come from experts who have been active in planning, managing and fighting to conserve water supplies for decades.

These changes will be needed because many scientists warn the river is very likely in the next 20 years to be carrying 9 million to 11 million acre-feet annually — down from 15 million during the 20th century and around 12 million since 2000. Compounding that problem, residents of the seven river basin states and Mexico have used at least 14 million acre-feet annually for most of this century. Those states are the Lower Basin's Arizona, California and Nevada and the Upper Basin's Colorado, New Mexico, Utah and Wyoming.

Our water future on many fronts:

Mark Wilmer Pumping Station on Lake Havasu. The six 66,000-horsepower pumps lift Colorado River water more than 800 vertical feet into Buckskin Mountain Tunnel and the Central Arizona Project canal. Phoenix and Tucson heavily depend on CAP water, with Tucson's drinking water coming exclusively from that canal system.

CAP water prices to go up

As reduced water supplies must be spread among the same number of customers, the price per gallon must rise.

CAP rates could go 62% higher by 2028, based on current plans for water delivery cutbacks from the river. Tucson residents won't see that steep of an increase in their water bills, however. The cost of buying the water is one of many factors contributing to the cost of water sold at the tap.

But rates charged by CAP will likely soar even higher once the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation follows through with its plan to cut 2 million to 4 million acre-feet of river water supplies across the seven-state Colorado River Basin. Then, CAP will have to spread its fixed operating costs for the project over an even smaller water supply. The $4 billion project delivers river water to the Tucson and Phoenix areas via a 336-mile-long canal system.

At some point, it's not unthinkable that rates will go so high that low-income and lower middle-class families won't be able to afford them, said CAP board member Mark Taylor, chair of CAP's Power and Finance Subcommittee.

"I personally believe water is way too cheap for its value that we get from it," said Taylor, who sat on Tucson's Citizens Water Advisory Committee for 12 years until earlier this year. "We're replacing a very scarce resource. It’s only priced as to what it costs to distribute and transport — not the cost to replace it with new sources.

"We all know new sources will be much more expensive. We all know costs will go up. They will have to go up a lot more in the coming years," Taylor said.

Many families in low-income areas such as South Tucson already can't afford to pay water bills, said Roxanna Valenzuela, a current Citizens Water Advisory Committee member and a just-elected South Tucson city councilwoman.

"The majority of their income is already going to rent and utilities. It’s going to impact them dramatically. You know that’s going to determine if they can afford groceries or not. People are living day to day here. They are just like one paycheck away from disaster," said Valenzuela, director of a community land trust and a community organizer for the Casa Maria Soup Kitchen in South Tucson.

The Whitsett Intake Pumping Plant is the first of five pumping stations that carry Colorado River water over mountains and through the desert and to Southern California faucets. California has the right to the largest single share of Colorado River water for its farms and cities.

She noted that South Tucson's median household income is very low. The median of $28,700 is barely half the median household income for the entire Tucson metro area, 2020 census data shows.

CAP's total water charge to cities like Tucson and Phoenix in 2022 was $240 an acre-foot. By 2028, the rate could approach $400 an acre-foot. By then, CAP will likely be taking a 50% cut in its total supply, compared to around 30% in 2022, even before possible cuts ordered by the bureau are considered.

Tucson Water utility customers face proposed rate increases of 5.5% a year annually from fiscal years 2023-24 through 2026-27. In part, those proposals were triggered by higher CAP charges. As part of that increase, Tucson Water proposes to raise a longstanding charge it imposes to cover CAP delivery costs from 70 cents to a dollar for every 748 gallons a homeowner or business consumes.

The Tucson City Council will hold a hearing on the proposed increases Jan. 10.

Tucson Water already has good programs for helping low-income residents meet their water bills, CAP's Taylor said. One program provides monthly water bill discounts to low-income customers, with the utility's budget making up the difference between what low-income customers pay and what they would have paid without the discount.

About 4,800 utility customers got the discounts in fiscal year 2021-22 at a cost of about $1.7 million. That's more than twice the number of customers and more than three times the cost of nine years ago.

"More likely, the utility will have to do more in the future," Taylor said.

Paul "Paco" Ollerton and his dog, Aggie, look toward the canal system that delivers Colorado River water to his farm near Casa Grande in July 2021. Climate change, drought and high demand forced the first-ever mandatory cuts from the Colorado River water supply starting this year, and central Arizona farmers will be hit hardest.

Farm production will shrink

Farms in the seven Colorado River basin states use an estimated 70% to 80% of the Colorado River's water, so they will be the biggest target. While improved irrigation efficiency will bring some water savings, crop production must also shrink, experts said.

"Perhaps as high as 25% of land currently in production would be removed. To be smart about it, we should target the least productive land and/or the land that generates the highest salinity runoff," said Jeff Kightlinger, retired general manager for Southern California's six-county Metropolitan Water District.

To reduce farms' water use by a million acre-feet, for instance, "I think it will result in most of these scenarios in a reduction in agricultural production by 10 or 20%," said Bruce Babbitt, a former U.S. Interior secretary and former Arizona governor.

A bleak outlook for some sectors of Arizona farming operations is offered by Kathleen Merrigan, a former deputy U.S. agriculture secretary who now works at Arizona State University.

“In terms of the large-scale vegetable production that goes on in parts of our state, alfalfa production, which is a very, very thirsty crop, and cotton, also thirsty — these operations are at risk,” said Merrigan, executive director of ASU's Swette Center for Sustainable Food Systems.

Alfalfa and cotton, both big water users, are grown on more acreage than any other Arizona crop, and alfalfa is grown on more than double the number of acres devoted to any other crop, ASU said in a recent news release.

But a recent survey found that nearly 75% of 650 farmers in 15 Western states had reduced their harvests due to water supply issues, ASU reported. Among Arizona respondents, 40% removed orchard trees or other multi-year crops because of water restrictions, said the American Farm Bureau Federation's survey.

Farmhands wrap a bale of cotton in a tarp while harvesting at the Pacheco Farm in Marana in October 2020. Roughly 1,150 acres of cotton were harvested in Pacheco's fields that year. Alfalfa and cotton, both big water users, are grown on more acreage than any other Arizona crop.

An environmentalist who has fought to protect river flows is dubious about the potential for increased efficiency to keep agriculture afloat.

"Some farmers will be going into bankruptcy. Everybody’s doing efficiency, and that works for now. It doesn’t work to the end of the century," said John Weisheit, director of the Moab, Utah-based group Living Rivers. "There's going to be more people, more demand, more evaporation, more heat and less snow. They can conserve water and save Lake Powell and Lake Mead. They are still going to end up short."

"In the 1970s, farmers were using 90% of the water, now they are using 80. They already have reduced their consumption. Now we are asking them to reduce it even more, while the cities are welcoming people to live in their communities," Weisheit said.

But we're also going to have to deal with the fact that farmers generally have the most senior rights to river water, said Babbitt and Kathy Jacobs, a longtime University of Arizona climate scientist and former top state water official. In Arizona, the rights are in the hands of farmers from Yuma north to the Colorado River Indian Reservation in Parker, and beyond.

That means farmers must be compensated for giving up water. The Bureau of Reclamation is offering up to $400 an acre-foot of federal dollars to compensate users for giving up river water. Yuma-area farmers want $1,500 an acre-foot.

"It’s going to be politically impossible for agriculture to sit on (their water rights), and say the cuts will have to come mainly out of municipal supplies, and that the Central Arizona Project will have to shut down and the Metropolitan Water District will have to shut down," Babbitt said. "Either agriculture voluntarily comes to the table and joins this discussion on where the cuts will be made, or it will be done for them."

Clearly, cuts in agricultural water use will have to be proportional to future river flows, said Jacobs, director of UA's Center for Climate Adaptation Science and Solutions.

"But due to the farms' senior rights, it's not just a question of who should restrict their water use. The question is 'what is the legal potential to cause that to happen?' Those folks have very strong legal rights and they will try to protect them."

Water flows through a farm irrigation channel along Marana Road. Farms account for at least 70% of Arizona's total water use.

Higher food prices, more political pressure

As farm production decreases, the prices people pay for a variety of food products will also rise and some crops may be harder to find, experts said.

While federal dietary guidelines say we should eat a half-plate of fruits and vegetables a day, “Where in the world are those fruits and vegetables going to come from? They're going to be imported," ASU's Merrigan said. "They may not be produced as safely. They may be produced using pesticides that we don't allow here in the United States for toxicology reasons.”

The U.S. will need to look at food security issues — "how much of our food is going to be exported," said Kightlinger, now interim general manager of the Pasadena Department of Water and Power. "We've allowed markets to dictate what’s more efficient to grow. We export alfalfa and almonds. Some of that may have to be rethought for food security if we have a shrinking portion of agriculture."

Babbitt and Jacobs also agreed tighter water supplies will increase pressure on farms to sell some of their water rights to cities. That's almost certainly going to cause controversy, as has happened in Arizona over a couple of proposals by the CAP and the town of Queen Creek to buy such rights from riverfront farmers.

"If CAP deliveries get cropped down below 500,000 acre-feet (compared to 1 million acre-feet scheduled next year), there's going to be enormous pressure. That’s the big issue all over the West these days," Babbitt said. "That is going to be a difficult political fight. There hasn’t been much discussion about that. Everybody wants to avoid the issue."

Jacobs said she hopes water rights transfers can be seen as a partnership "rather than some sort of predatory relationship."

"It’s possible to negotiate conditions that are very positive for agriculture as well as for cities. There are plenty of examples. We’ve seen the Metropolitan Water District pay for the lining of irrigation canals of various (agricultural) districts in California in order to harvest water for the cities in the L.A. area. That was a negotiated agreement. It benefited everybody."

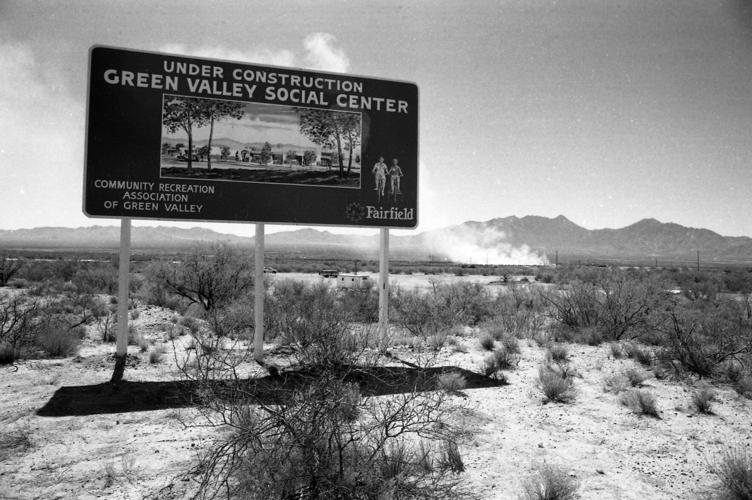

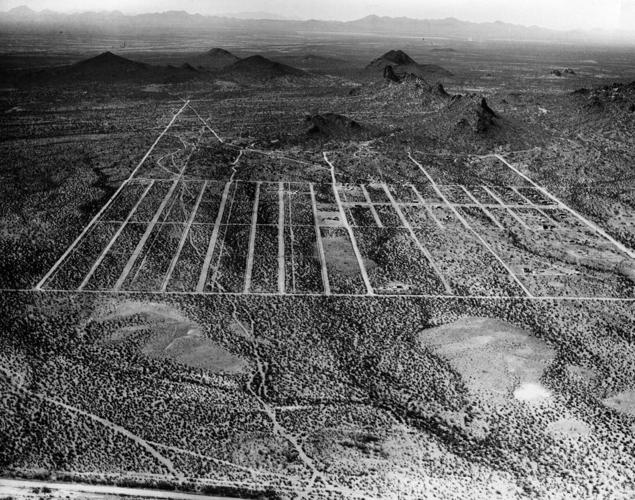

Dirt roads outline a planned subdivision in the desert southwest of Mission Road in Tucson in 1953. Until 1992, when Colorado River water arrived via the Central Arizona Project, there were concerns the growing metropolis of Tucson would pump the aquifer dry.

Using less on lawns, toilets, appliances

As water supplies shrink for cities as well, the average resident's daily water use will very likely shrink to as low as 50 to 60 gallons daily, Kightlinger said. That matches Sydney's 55 gallons per day use but tops Melbourne's 43 gallons. Those Australian cities' uses started dropping more than a decade ago due to a drought even more severe than the U.S. Southwest's has been.

Reaching those levels in the Southwest will require substantial, although not unthinkable, water use changes inside and outside the home, experts say.

In recent years, Tucson's daily per-person use has ranged from 76 to 82 gallons, less than half of that in the 1970s and early '80s. The average Arizona resident uses about 146 gallons daily, says the Arizona Department of Water Resources. Phoenix, Las Vegas, Los Angeles and Albuquerque residents use 99, 110, 110 and 125 gallons per person daily, respectively.

Water use has been reduced in Las Vegas by cracking down on lawns. Las Vegas-area local governments banned new front lawns in the early 2000s and all new grass planting, except for schools, parks and cemeteries, during the past year. On summer 2022, county commissioners there agreed to limit residential pool sizes to 600 square feet.

Scottsdale recently approved grass removal rebates up to $5,000 per property and a rebate for in-ground pool or spa removal of $400 plus $1 per square foot of water surface area.

Tucson is considering banning the planting of ornamental grass in new businesses and at some apartment buildings. Many other Southwestern cities are signing on to a regional letter committing to future passage of additional bans on ornamental turf.

Jacobs doesn't foresee grass bans being very controversial here, unless we "absolutely outlaw lawns in peoples' backyards," because Tucsonans have already reduced turf a lot. But they might be very controversial in areas of Phoenix where water is served by the Salt River Project utility. Its lands have existing water rights for the purpose of planting grass, she said.

All experts interviewed expect we'll also be getting more and more efficient toilets, faucets, shower heads and other plumbing fixtures, keeping indoor water use on an even steeper downward path. Toilets, for instance, needed 5 gallons per flush in the 1970s, but you can easily find toilets today that only need a gallon or so.

Sign announcing the Green Valley Social Center in June 1975. The CAP canal doesn't extend to Tucson's southern suburbs, which depend on groundwater pumping. As the Southwest's water woes intensify, experts worry that more ancient groundwater will be used up and not replaced.

In Tucson, the City Council has approved a requirement that all new development install fixtures that meet Environmental Protection Agency standards. Existing homeowners continue to get rebates from $100 to $200, covering much of the cost of toilets and washing machines.

But many low-income owners of older Tucson homes can't afford to buy high-efficiency washing machines even with rebates, said Gary Woodard, a private water consultant and researcher. Low-income families can get free toilets from the city rebate program if their old toilet uses at least 1.6 gallons per flush. But when other fixtures are considered, in general, older homes owned by lower-income families are a challenge for water-saving because they usually have higher water using appliances, he said.

The time for homeowners to pay back the cost of their new appliances through lower water bills is no more than 18 to 30 months, but "often low-income households can't afford to spend $100 now if it’s even if it’s going to save them $3 a month forever," Woodard said.

A home with a pool in the Tucson desert in 1960. Private pool numbers have grown steadily here as the population boomed, but now there's talk about whether pool covers should be required in order to reduce evaporation.

Covering pools

As for private swimming pools, their numbers have grown steadily in Pima County since 2015, with up to 1,450 pool construction permits issued annually by local governments. The numbers of annual permits issued from 2009 through 2014 were in the 400s and low 500s.

Jacobs, Kightlinger and former Arizona Department of Water Resources Director Kathleen Ferris see little or no chance of pools being banned anywhere in the Southwest. But Ferris and Kightlinger see some possibility authorities could require pool owners to cover them, to limit evaporation.

If you are buying a place without a pool, it's a lot easier to stop the new owner from putting in a pool than to force someone to take out an existing pool, said Kathy Ferris, whose Phoenix-area home has had a pool for 35 years.

Having pools is "how we lived in the desert," Ferris said. "It's what people do in the desert with their kids in the summer. Also, the cost of taking out a pool is very steep. Would people get rebates for doing it?"

if you're buying a place that doesn't have a pool, it's easier to say on the front end that pools are no longer to be allowed than it is to say take out a pool, she said.

Whether people keep adding and maintaining pools will likely become personal issues of high cost and peer pressure rather than targets of bans, said Jacobs.

As conservation grows more necessary, increasing water costs and covering pools "are obvious options that preserve opportunities for personal choices," said Jacobs, director of ADWR's Tucson office from 1988 to 2003.

Researcher Woodard found in an October 2018 study that 21% of a sample of Tucson households had pool covers, with 97% of them claiming to use them at least sometimes.

But in general, covers were used most heavily from November through April and much less in summers, when evaporation peaks, he said. Only 6% of the pool owners covered them in July and August, he said.

The covers' water savings are limited if they're used in spring and fall to keep the water warmer, Woodard said. If the pools are used at all then, "that increases evaporation substantially over what it otherwise would be," he said.

"I’m not anti-pool cover, but they clearly are not a panacea for pool-related water use," Woodard said.

The Central Arizona Project is a 336-mile canal in Arizona that supplies Colorado River water for the Phoenix and Tucson area, agriculture and several Native-American tribes. Construction began in 1973 and was substantially complete by 1994. This portion is located near Sandario Road and Mile Wide Road west of Tucson on March 17, 2021. Video by: Mamta Popat / Arizona Daily Star

Back to pumping ancient groundwater?

One way Arizonans can keep the loss of Colorado River water from crimping their lifestyles would be to revert to the rampant groundwater pumping that dominated the state before CAP came online in Phoenix in 1985 and in Tucson in 1992.

Just the possibility that would happen keeps Ferris up at night. More than four decades ago, she chaired a State Groundwater Study Commission that drafted the pioneering 1980 Arizona Groundwater Management Act. One of its goals was to limit pumping in favor of renewable CAP water from the Colorado.

Despite widespread predictions that Colorado River cutbacks will slice peoples' water use, Ferris said she’s not sure things are going to be that much different in the next 20 years because of readily available, fossil groundwater supplies. That water has sat underground for millions of years and can't be replaced once withdrawn.

If large-scale pumping resumes, she fears a resurgence of the land subsidence and earth fissuring that were common before the 1980 law passed and that still strikes rural areas where groundwater remains unregulated.

“How we address this problem in the next few years will determine how inhabitable this place will be in 20 or 30 years. We don’t have 20 or 30 years to figure this out. We have to start taking action now. (But) all we do is talk talk talk talk talk talk," Ferris said.

"We will see a lot of heartache. I think we will see a lot of ground fissures and subsidence that will affect homes and the value of property. It will be a signal to the rest of the country that this state is in decline."

Tucson may have to resume some pumping of ancient groundwater over the coming years. It's done little of that since the early 2010s when it started putting virtually all its residential and business customers on CAP water. It now recharges about 30% of its CAP supply every year for long-term storage in various aquifers, and serves the rest to customers after recharging it, then pumping it out of the ground.

As of now, the city has stored about five years worth of CAP supplies underground, -- more than 560,000 acre feet. Talhe state-run Arizona Water bank has stored almost that much additional CAP water underground in the greater Tucson area. But that water could be used by any Tucson-area entity with CAP rights. Tucson Water and ADWR officials can't say how much of that water could be used by Tucson compared to other cities and private water companies in this area with CAP water rights.

But if the bureau orders a large enough cut in Colorado River deliveries to Arizona, Tucson Water Director John Kmiec has said the city may have to start pumping out some of that stored CAP water to supplement its diminished annual CAP deliveries. When and if that stored supply is gone, the utility would then likely have to revert to pumping native groundwater.

In 1980, the state estimated that farms and cities in the three most populous counties — Maricopa, Pima and Pinal — were pumping around 2.5 million acre-feet more groundwater every year than rainfall was putting back in. Thanks to the groundwater law and the arrival of CAP, the overdraft plunged to 180,000 by 2010. But by 2019, the last year for which statistics are available, it had rebounded to about 480,000, state records show.

Groundwater levels across the Colorado River Basin have, over the past 20 years, declined faster than water levels at Lakes Powell and Mead, a study has found. The study is led by Jay Famiglietti, a longtime water researcher who will soon join ASU as a professor.

"Most of the groundwater losses in the basin are happening in the Lower Basin, and mostly Arizona," said Famiglietti, now executive director of the University of Saskatchewan's Global Institute for Water Security. "The groundwater supply is so critical to the future of the region that it is not an exaggeration to call it an existential crisis."

Ferris said she's concerned there will be efforts in the Arizona Legislature to loosen the existing state groundwater law, to make it easier, for instance, to prove that a new development meets state requirements for having an assured, 100-year water supply.

"We've got to stop thinking this groundwater is inexhaustible. We have to start planning for a future that relies on less groundwater."

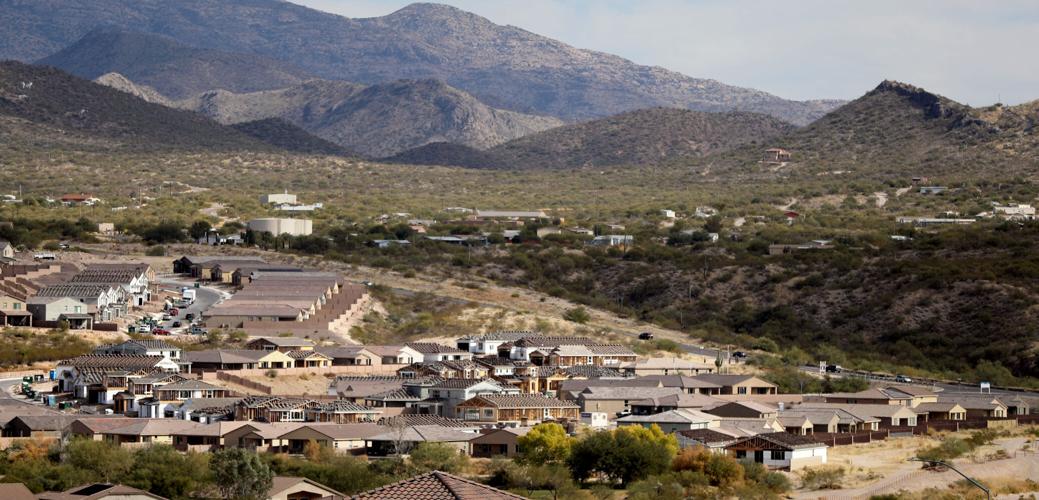

New homes now under construction in Rancho Del Lago along Colossal Cave Road in Vail. As our water crisis deepens, "It’s not required that we limit growth; I do think that conservation needs to be a much larger part of the equation," says Kathy Jacobs, a University of Arizona climate scientist.

Toilet to tap foreseen

That's been the catch phrase for years for people uncomfortable with treating wastewater to make it safe to drink. But now with Colorado River water slowly disappearing, many experts say that idea's time has arrived.

A key reason is that while treating wastewater that heavily is expensive, it stretches existing supplies rather than requiring governments to invest even more money developing more expensive supplies such as seawater desalination, or building a pipeline to import water from less arid regions of the U.S.

"The best source of near term augmentation is water recycling and reuse," Babbitt said. "It should be near the top of the augmentation list."

While in the past many citizens have recoiled at this water solution, Ferris said she believes people will now accept it if it's handled correctly. In selling projects like these to the public, officials must also demonstrate that recycled wastewater will be used to supplement existing supplies — not to support new growth, she said.

Scottsdale has run a major water recycling plant for 20 years that creates 7 billion gallons a year of drinkable, reused wastewater. The city's Advanced Water Treatment Plant puts wastewater from a conventional sewage plant through a series of processes, including reverse osmosis, filtration and the use of ozone, to produce water that exceeds the quality of bottled water, Scottsdale Water officials say. Then, they inject the water into either the city's drinking water aquifer or into a reclaimed water distribution system serving golf courses and other turf uses.

Scottsdale has had a state permit since 2019 authorizing "direct potable reuse," in which the recycled water goes directly into the drinking water system. But the permit is only valid for demonstration purposes. The city provides about 2,000 samples of the water annually to people who tour the plant, and has twice held events where people pay to drink locally brewed beer made from recycled water.

The Arizona Department of Environmental Quality can't allow recycled water directly into drinking water systems until it develops more detailed rules. That work started this year, after the Legislature required the rules by the end of 2024.

Once the rules are in place, Scottsdale Water officials intend to seek their City Council's permission to apply for a state permit to run the plant for drinking water.

"It's almost like we're the test dummies for it," said Scottsdale Water spokeswoman Valerie Schneider.

As for Tucson Water, the city has no plans to pursue even indirect reuse of wastewater for drinking in the foreseeable future, utility spokeswoman Natalie DeRoock said in November.

A much bigger plant for treating wastewater to drink is being studied by Southern California's Metropolitan Water District. The $3.4 billion project would create 150 million gallons of clean drinking water daily — nearly eight times more than the Scottsdale plant.

That would be enough to serve more than 500,000 homes every day, and produce around 50% more water than Tucson Water customers consume in a year. For now, however, MWD officials say this project would be only for indirect reuse, just like Scottsdale's. The reason is the same: California also is developing regulations allowing direct reuse of wastewater for drinking.

Officials hope to start construction on the project by 2025, have a preliminary phase online in 2028 and a second phase operating by 2032.

Catching the rain

Rainwater harvesting barely existed here 40 years ago, but it's now big business in Tucson. And it's likely to get a lot bigger here, and across the Southwest, as other water supplies disappear.

Today, about 30 Tucson businesses install cisterns and other kinds of equipment to help homeowners and businesses capture rainfall for their outdoor landscaping. A few people have even installed harvesting systems to capture rainwater for their pools.

In 30 years, Brad Lancaster, a Tucson author and advocate of rainwater reuse, said he wouldn't be surprised if water harvesting here matches that of Australia, where cisterns and other rainwater harvesting tools are now common.

As long ago as 2014, 45% of all homes in Adelaide, Australia, had rainwater harvesting systems, and in Sydney, you can't build, renovate or make a change without installing a cistern as part of your water supply.

Students at Mission View Elementary School in Tucson stand in line in 1960 for a drink of water in the late summer heat. Today, Tucsonans use significantly less water per person than do those in Phoenix, Los Angeles, Las Vegas and Albuquerque.

Lancaster drinks rainfall coming off the roof of his Dunbar Spring home. That Tucson neighborhood now captures 1 million gallons a year along its streets and in public right of ways, Lancaster said, adding, "We’re not done at all. We can and have to do at least 30 times more of that; I did a simple calculation that we have over 50 million gallons of rain falling on our neighborhood in a year and I’m only talking about public right-of-way stuff."

Less consensus exists on the feasibility of capturing rainwater on a larger scale, through building small dams along washes or large water storage ponds such as one that Pima County uses to furnish water for the Kino Sports Complex.

Los Angeles County voters in 2018 approved property tax increase in part to build projects like grassy swales and dry wells to capture nearly 100 million gallons of storm water runoff a year that otherwise would speed into the Pacific Ocean. But county officials estimate it could take 30 years to build all the projects.

Ferris and Kightlinger question the feasibility of the very idea of storm water capture, because of its costs and potential legal difficulties because the rights to water flowing down a wash are often owned by landowners downstream.

Researchers at all three major Arizona universities are about to embark on a three-year, $3.7 million project to investigate a different kind of storm-water capture. It will involve finding the best locations across the state to corral and ultimately recharge rainfall into various aquifers, for future use. The goal is to store runoff so it's not lost to evaporation, which accounts for 75% to 90% of all precipitation in Arizona, said Jacobs, co-lead investigator for the project along with Neha Gupta of UA's Institute for Resilience.

The Arizona Board of Regents signed off Nov. 18 on the project. While the Arizona Department of Water Resources hasn't specified how the captured runoff would be used, clearly it could later be pumped for human use, serve to upgrade the state's riparian habitats or help stabilize or restore flows in nearby rivers, Jacobs said.

A couple of sightseers take in the view from Hite Overlook, where the Colorado River enters what was once the upper reaches of Lake Powell. Now dry, Hite Marina has been closed by the National Park Service.

Managing the crisis

In the worst case scenario projected by researchers — a 60% decline by 2060 in Colorado River flows from 20th century levels — many water experts and political leaders say the resulting cutbacks will cause serious economic dislocation, but will be manageable.

Among them is Babbitt, who said he believes that while water cutbacks on farms will cause some job losses and boost some food prices as land goes out of production, agriculture will still largely survive.

"Bear in mind that of the existing water uses of agriculture, more than half of it is for growing alfalfa and grass, more than half the water use is for cattle feed," he said. "That's true in both basins. There will be some reduction in the growing of alfalfa, winter wheat, sorghum and other feed, but those kind of crops can in fact be grown elsewhere."

Because so much of the river water goes to agriculture, the cities' water problems are more manageable, too, Babbitt said.

For instance, with 40% of urban water use in the West going outdoors (Tucson Water customers use 30% of their water outdoors), that leaves plenty of room for water savings there. As for indoor use, even if 40% isn't eliminated by conservation, the water used simply goes into sewage treatment plants and can be recycled, giving cities a large new water supply, he said.

Weisheit, of Living Rivers, who has been warning for decades that the river is in trouble, is much more pessimistic. While conservation may reduce individuals' water use for a time, he said that by 2100, climate change will require the use of more water, not less.

As it gets hotter, "plants are thirstier. The air is thirstier. Soils are thirstier," said Weisheit.

"By the end of 21st century, more people will override the conservation that we do. Not only is the water needed for daily living, you have to grow food for these people."

Longtime Arizona Daily Star reporter Tony Davis talks about the viability of seawater desalination and wastewater treatment as alternatives to reliance on the Colorado River.

Can our population keep growing?

Even with Colorado River cutbacks, Kightlinger and Jacobs say they believe the Southwest will still have enough water from groundwater, recycled water and other surface water sources to allow growth to continue without major reductions in its pace. But both conditioned their optimism with caveats.

"I don’t think that reductions in water availability necessarily have to lead to a reduction in growth. There’s a lot of perception associated with this that might affect things as much as actual shortages," Jacobs said. "(The water problems) could discourage investors or people who read newspapers about water shortages and that may encourage them to move elsewhere.

"I don’t think with the amount of water we have available in the state there’s any reduction required. It’s not required that we limit growth; I do think that conservation needs to be a much larger part of the equation," she said. "If we have farsighted leadership and the resources required to carry it out, this transition (away from Colorado River water) could go relatively well. If we refuse to take farsighted actions now, we are going to pay for that."

Kightlinger added, "I think we can manage the population levels and growth with the resources we have. It will have to be as highly efficient growth as possible. We are going to have to make sure the water footprint we have with that growth is as small as possible."

Ferris said she doesn't know if it's politically feasible to limit where people can live or move to. But it may be necessary to restrict new home building to ensure growth doesn't occur in areas that depend mainly on nonrenewable groundwater due to the risks of land subsidence, fissuring and diminishing water quality as wells go deeper, she said. She noted, however, that based on how groundwater has been managed here in recent decades, "the political will for doing that is not good."

The problem is nobody in government is thinking about the truly long term, said Living Rivers' Weisheit.

While Arizona does require proof of a 100-year water supply for allow new home building in urban areas, "Why isn't that a 1,000-year supply?" he asked.

"Everybody’s thinking till the end of their employment and retirement. They're concerned about the here and now. They're putting this burden on future generations and I don’t see them stepping up to the plate to solve this problem for future generations."

Photos: The receding waters of Lake Powell, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area

Tom Wright hikes past the beached marker for Willow Canyon where it joins with the Escalante River, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah.

A big horn sheep stands with the moon as a backdrop, looking over Fiftymile Creek, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah.

Tom Wright walks through the shaft of light peeking through the narrow openings of the formation called the Subway in Fiftymile Creek, accessible since the waters of Lake Powell have fallen dramatically.

A narrow sliver of sky is visible overhead through the narrow opening of the formation called the Subway, Fiftymile Creek, accessible since the waters of Lake Powell have fallen dramatically.

The dark streaking, called Desert Varnish, is from the seepage of oxidation in the rocks, and is beginning to erase the "bathtub ring", the lighter colored marks left by the waters of Lake Powell on canyon walls, Fiftymile Creek, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah.

The remains of a small boat, underwater for years, reemerges due to receding water levels of Lake Powell in the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah.

Frank Colver makes his way over the dried and cracking silt left where the Escalante River joins Lake Powell, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah. The receding water of the lake has the river cutting through the decades of accumulated silt to form a delta where it meets the lake.

A warning buoy sits high and dry far from the end of the closed public boat ramp at Bullfrog Bay, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area.

A line of tires that were once breakwaters at Bullfrog Bay Marina are now stranded on the rocky landscape high above the current water levels at the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah.

A pedestrian ramp lies well above the water levels at Bullfrog Bay in the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah.

A stranded wakeless zone buoy sits on the cracking silt outside the new shores of the Bullfrog Bay Marina, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah.

The end of the ferry ramp ends well short of the new water levels of Bullfrog Bay on the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah.

An early riser watches the sun come over the low waters of Bullfrog Bay Marina, Glen Canyon National Recreation Aria, Utah. The lighter colored areas on the canyon wall mark previous water levels.

A group of river rafters drift west on the current of the San Juan River outside Mexican Hat. The San Juan feeds Lake Powell.

The tops of a few cottonwood trees begin to poke out of shrunken water of Lake Powell, Fiftymile Creek, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah.

The remaining large water craft and house boats are crowded together in one of the last areas of water deep enough to support them at Wahweap Mariana, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Page, Ariz.

The waters of Lake Powell are twenty to thirty feet below the end of the public boat ramp at Wahweap Mariana, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Page, Ariz. Personal non-powered craft still use the ramp to unload, but must be carried up and down the banks to reach the water.

A view north from the Wahweap Marina Overlook show the shrunken waters around the marina in Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Page, Ariz.

The underside of Gregory Natural Bridge, passable for the first time in almost 50 years, over the Fiftymile Creek, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah.

The moon rises over Gregory Natural Bridge, passable for the first time in almost 50 years, over the Fiftymile Creek, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah.

The exposed penstocks (intakes to the power turbines) on Glen Canyon Dam in the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Page, Ariz. The water level is at its lowest since 1967, when the dam was still being initially filled.

A group of sightseers get a look at the Glen Canyon Dam during a boat tour of Lake Powell, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Page, Ariz.

A small fishing boat ties up on the breakwater just outside the intakes for the Glen Canyon Dam, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Page, Ariz.. The penstocks (water intakes to the power turbines) are revealed for the first time since 1967 when the Lake Powell was being filled.

Swimmers and bathers use the jagged shores of the newly exposed banks of Lake Powell just above the Glen Canyon Dam, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Page, Ariz.

The Glen Canyon Bridge lies in front of electrical towers with feeder lines rising from the hydroelectric plant in the Glen Canyon Dam, Page, Ariz.

Glen Canyon Dam from Glen Canyon Bridge, Page, Ariz.

Small power boats on the Colorado River head upstream just below the Glen Canyon Dam, Page, Ariz.

Wade Quilter walks through the remains of cottonwood and Russian olive trees washed down and joined with silt to form a natural dam where Willow Canyon joins with the Escalante River, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah,

The remains of a big mouth bass lay in the silt just above where the Escalante River joins Lake Powell, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah.

The formation known as The Cathedral in the Desert on Clear Creek, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah. The re-emergence of the formation is drawing sightseers after being submerged for some 50 years.

Tom Wright feels the water oozing from the rocks in the formation known as Cathedral in the Desert on Clear Creek, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah. The re-emergence of the formation is drawing sightseers after being submerged for some 50 years.

Frank Colver takes a quiet moment and plays a handmade flute near the waterfall in the formation known as Cathedral in the Desert on Clear Creek, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah. The re-emergence of the formation is drawing sightseers after being submerged for some 50 years.

Jake Quilter walks down the newly cut banks of Clear Creek just outside Cathedral in the Desert, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area Utah. The sand is silt left behind by the receding waters of Lake Powell.

The tops of cottonwood trees that used to be under a hundred feet of water in Lake Powell are visible again in Clear Creek, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah. The deep water preserved the remains of the trees.

Boaters have to zig-zag through the rocks emerging due to receding waters of Lake Powell, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Page, Ariz.

Several images combined for a panoramic view of the Colorado River where it runs through the what once was Hite Marina in the Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah.

A couple of sightseers take in the view from Hite Overlook over the Colorado River and the closed Hite Marina, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah.

Lone Rock, jutting out of the dry bed, would usually be surrounded by Lake Powell but is now well clear of the water, Glen Canyon National Recreation Area, Utah.

Tires that used to hold the lines well below the surface of Lake Powell are suspended over the water at Antelope Point Marina, Ariz.

Sightseers twenty or thirty feet above get photos of the low water levels of Lake Powell from the public boat ramp at Antelope Point Marina, Ariz.

The pedestrian access ramp ends abruptly twenty feet over the new Lake Powell surface at Antelope Point Marina, Ariz.

The entrance to the pedestrian access ramp of the Antelope Point Marina is taped off after being cutoff from the docks due to receding waters of Lake Powell.