In 1939, prominent Tucson developer John Murphey received a fill-in-the-blank template from the Federal Housing Administration, outlining restrictions he should use to protect the value of what would become Broadway Village, the city’s first shopping center.

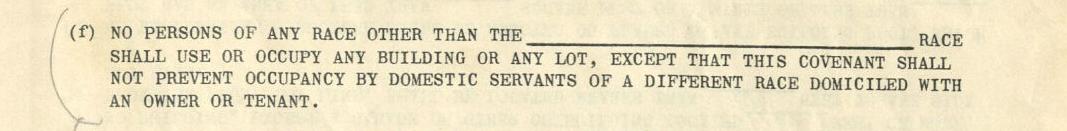

One of the suggested covenants read: “No persons of any race other than the (blank) race shall occupy any building or any lot,” unless they are employed there as domestic servants.

As it turned out, Murphey didn’t need the FHA’s advice.

Almost a decade earlier, the future civic leader and philanthropist broke ground on Catalina Foothills Estates, a new desert enclave north of Campbell Avenue and River Road that advertised “unusual homes among the sahuaros,” but only for people of “the white or caucasian race.”

A nearly identical rule would be written into the founding documents for Broadway Village.

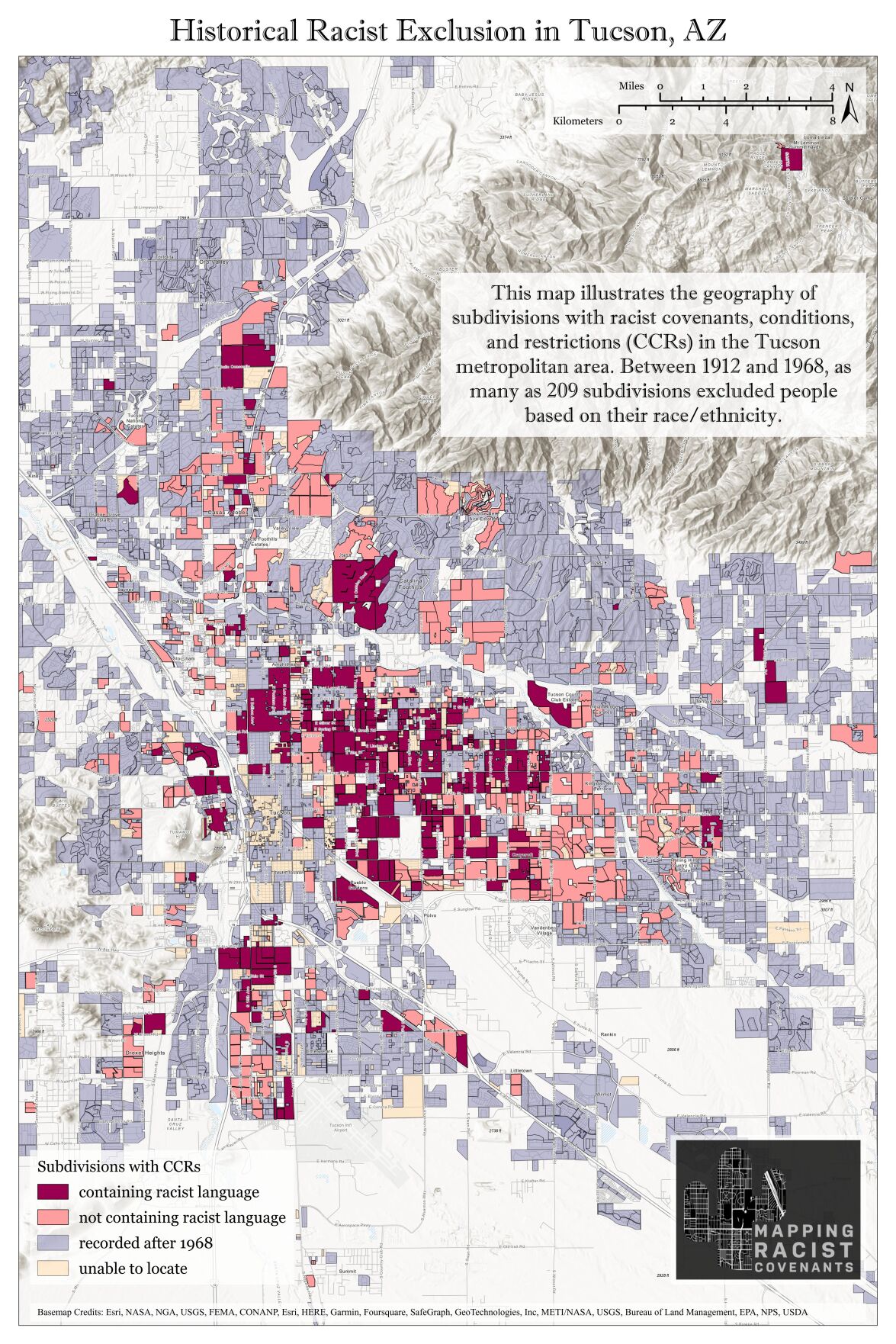

Such race-based housing restrictions were outlawed for good more than 50 years ago, but findings just released by researchers at the University of Arizona reveal how common and widespread the practice was.

The Mapping Racist Covenants Project spent the past 10 months tracking down and examining the covenants, conditions and restrictions — or CC&Rs — for more than 750 subdivisions in and around Tucson. More than one quarter of those neighborhoods had rules prohibiting nonwhite residents.

The results have been compiled in a new online map stained with a magenta patchwork of places founded on exclusion.

The race-restricted subdivisions stretch from the Tucson Mountains to Houghton Road and from North Oracle Road in present-day Oro Valley to Nogales Highway and Valencia Road. A magenta rectangle high in the Catalina Mountains marks the community of Summerhaven, where rules recorded in 1942 state that “property shall never be occupied by or sold to any member of the black race.”

A document distributed to developers by the Federal Housing Administration in the late 1930s shows sample property covenants, including a fill-in-the-blank restriction based on race.

“It’s been sobering,” said Jason Jurjevich, a UA professor and population geographer who led the research project. “I think what we’re seeing in Tucson mirrors a lot of what we’re seeing in other cities, in terms of the extent to which these were part of housing development.”

The project looked at local neighborhoods built between Arizona statehood in 1912 and the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968, which banned racist property covenants. Researchers tracked down the CC&Rs for 756 of the 1,338 subdivisions developed during that period, and found racist covenants in at least 209 of them.

In all but a few cases, those illegal and unenforceable restrictions remain on the books today, largely because of the complications involved in changing what amounts to a private contract among property owners.

Though meaningless under the law, the racist language still shows up in the stacks of documents homebuyers have to sign when they move into one of these neighborhoods. Imagine the emotional trauma of discovering something like that, especially for people of color, Jurjevich said.

“And this is being repeated and has been repeated for decades,” he said. “I think that’s something you can’t ignore.”

Across the map

Jurjevich estimates that the magenta colored portions of the map within the city limits are currently home to roughly 190,000 people, 35% of Tucson’s total population. “So one in three Tucsonans — more than one in three — live in a subdivision with a racist covenant,” he said.

Jurjevich is one of them.

Researcher Jason Jurjevich in the Environment and Natural Resources 2 Building, 1064 E Lowell St. on Wednesday.

He lives in Encanto Park, a subdivision of the Miramonte neighborhood near Broadway and Country Club Road that excluded people of “African or Asiatic descent” and anyone else “not of the White or Caucasian race” starting in 1947.

He and his husband, Charles Walker, who is Black, found out about the old covenant just as they were about to close on their house in 2021.

The new online map produced by the research team is interactive, so you can search any address to see if the surrounding neighborhood was once restricted by race.

Click on a subdivision, and a pop-up window gives you its name, the year its covenants were recorded and whether it had race-based exclusions. It also provides the wording of any discriminatory rules and a link to the original CC&Rs, digital copies of which are now stored in the UA’s electronic research repository.

Some of those founding documents bear the familiar names of prominent Tucson families — people who once held elected office; people with roads and buildings named after them.

A few of the documents include clauses giving the developer the authority to seize the property of anyone who fails to follow the racist covenants.

The map’s built-in filters allow you to sort by the various minority groups that were excluded or by the neighborhoods where discriminatory restrictions came with so-called “perpetuity clauses” to prevent them from expiring or being removed.

The overwhelming majority of Tucson subdivisions with racist CC&Rs, 81%, excluded people of color by enacting “white or Caucasian only” covenants.

But specific minority groups were also singled out. Researchers identified 20 different racial and ethnic terms used to block people from living in certain neighborhoods. The two groups targeted the most by far were Blacks, 69%, and Asian Americans, 68%.

Some 58% of subdivisions with racist CC&Rs also have perpetuity clauses that were aimed at keeping the discriminatory rules in place forever.

“This underscores to me that even if a subdivision or a neighborhood wanted to modify the language, most of them can’t,” Jurjevich said. “That’s my understanding of why there would need to be legislative action to allow subdivisions to change the language, even though it is illegal.”

You can also use the filters to highlight the handful of subdivisions — at least 17 by the research team’s count — that later canceled or removed their racist covenants, including two neighborhoods that got rid of the restrictions as far back as the late 1930s.

Under the layers tab in the upper righthand corner of the map, you can toggle through Census data that shows where people of color were living in 1960 and in 2020. Jurjevich called it a window into “the intersection between racist covenants and present-day and historical patterns of racial segregation in the city.”

“I think it’s important to tell the story, because it’s reflective of institutional forms of housing discrimination,” he said. “There are many ways in which this happened in the 20th century, and covenants are one of the least well understood forms.”

“Before I got involved in the project, I didn’t have an appreciation for how widespread racist covenants were not only in Tucson, but even across other cities,” he added. “There’s a colleague of mine in Milwaukee who mentioned a statistic that by 1930, half of all residential developments in the U.S. had racist covenants.”

Such discrimination was so commonplace at one time, it was often mentioned as an amenity in newspaper ads for new developments.

“See beautiful Catalina Foothills Estates” with its “large, well restricted building sites,” says one ad in the Arizona Daily Star from 1939. “Remember there is no dust in the foothills.”

Search history

UA Librarian Emerita Chris Kollen began researching discriminatory housing restrictions in Tucson in early 2021, after studying earlier mapping projects in Colorado, Minnesota, Washington state and Washington, D.C.

She and Jurjevich joined forces last year, and the Mapping Racist Covenants Project was officially launched in November.

The only way to track down the ugly old rules was to comb through all the neighborhood agreements they could find at the Pima County Recorder’s Office, Kollen said. “I didn’t have a sense of how difficult it would be.”

Kollen and Jurjevich were joined on the team by UA assistant professor and programmer Yoga Korgaonkar, graduate researcher Liz Wilshin and undergraduate researcher Claire Holloway. A group of about 10 volunteers helped them review, transcribe and verify all the information included on the website.

Christie Kollen laughs at Presta Coffee Roasters, S Avenida del Convento, August 17.

The work was funded with $60,000 provided by the University Libraries’ Digital Borderlands program through a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

A host of Tucson residents and institutions helped guide the mapping initiative, including the African American Museum of Southern Arizona, the Tucson Chinese Cultural Center, the Tucson Jewish Museum & Holocaust Center, the Southwest Fair Housing Council and the city of Tucson’s Housing and Community Development Department.

Staff members at the recorder’s office were also a huge help, Jurjevich said.

“There’s literally hundreds of hours involved in really telling this story,” he explained. “We were reviewing documents from the ‘20s, ‘30s and ‘40s that were difficult to read, were only available at the recorder’s office and were not digitized. We couldn’t just do a Ctrl-F and search for racist language. We actually had to read every document.”

And the work isn’t finished. So far, researchers have not been able to locate any CC&Rs for almost 600 of the subdivisions that were established between 1912 and 1968. They suspect there could be dozens or even hundreds more racist covenants still out there, waiting to be discovered.

“The words that I’m using to describe the numbers are ‘at least,’ because I think we’ll find more,” Jurjevich said. “What we’ve done is as much as we could do within the scope of the grant, but we didn’t catch everything.”

Relay race

The researchers unveiled their findings on Friday evening, during an event that featured a panel discussion on the legacy of housing discrimination and next steps for the community.

Delano Price was one of the panelists.

He was 8 years old when his family moved to Tucson from deeply segregated Gary, Indiana, in 1959.

They settled on Lester Street in Sugar Hill, one of a handful of predominantly Black neighborhoods in the community. Price went on to lead Tucson High to the state title in basketball during his senior year in 1969.

He said some of his white teammates back then used to speak fondly of his mother, who they knew from her work as a domestic servant at homes in their neighborhood. “It occurred to me that my mother could work there, but we couldn’t live there,” he said.

Still, Tucson was a far more diverse, multicultural place than Gary had been, at least outside the scattered, whites-only neighborhoods. “It was integration by circumstance,” Price said.

The career public school educator and coach now sits on the advisory board for the African American Museum of Southern Arizona, alongside his wife of 52 years, Jacquenese Barnes Price, a Tucson native and the first-ever Black member of the UA Pomline.

The couple also served as advisors to the Mapping Racist Covenants Project, a role Price said gave him the chance to swap first-hand accounts with Tucsonans from other minority groups impacted by institutional housing discrimination.

“It wasn’t so much that I learned new stuff. I learned new perspectives,” he said. “I learned so much from the experiences that each of us was able to share.”

Price hopes the mapping project will shine new light on the inequities from our not-so-distant past and spur action to finally stamp out the hateful language that’s still on the books in many of our neighborhoods.

It’s natural to be shocked and disgusted by what the researchers uncovered, he said, “but then you get over that and get to work. Become educated, learn as much as you can and pass it on. Think of it as a relay race, and you can’t drop the baton.”

Save or delete?

So what should be done with the racist rules that remain on the books in neighborhoods across Tucson? It depends on who you ask.

Marco Liu and his wife, Lydia Garcia Liu, live in the once-restricted Catalina Vista subdivision, southeast of Campbell Avenue and Grant Road.

About 10 years ago, when he was serving on the neighborhood board, someone suggested amending their 83-year-old CC&Rs to get rid of the covenant that excluded anyone of “African or Asiatic descent” or “not of the White or Caucasian race.”

Liu said board members eventually abandoned the idea because of the complicated amendment process involved, but not before they had a passionate debate about how — or even if — the offensive language should be erased.

He came down on the side of keeping it. Or, if it had to go, he wanted it to be struck through in a way that would still be legible, as a reminder of the community’s unsavory beginnings.

“To just change the rule and pretend like it never existed rubbed me the wrong way,” said Liu, who also participated in Friday’s panel discussion put on by the Mapping Racist Covenants Project.

Liu is the proud son of a Mexican mother and Chinese father who had to get married in Lordsburg, New Mexico, because interracial marriage was still illegal in Arizona at the time. He said he never experienced racism like his parents did, but he is keenly aware that there was a time, not that long ago in the grand scheme of things, when he would not have been allowed to live in the neighborhood he now calls home.

He feels strongly that discriminatory language like that should not be erased strictly for “appearance’s sake.”

After all, ashamed isn’t the only way to feel about our ugly past, the Tucson native said. “It’s actually something to be proud of in terms of how we overcame it.”