If you’re curious about what an asteroid is made of or you just want to see one get smacked with a spaceship, the local scientific community has you covered.

Researchers from the University of Arizona and the Tucson-based Planetary Science Institute are playing significant roles in the recent wave of asteroid exploration, including Monday’s controlled collision with a harmless space rock known as Dimorphos.

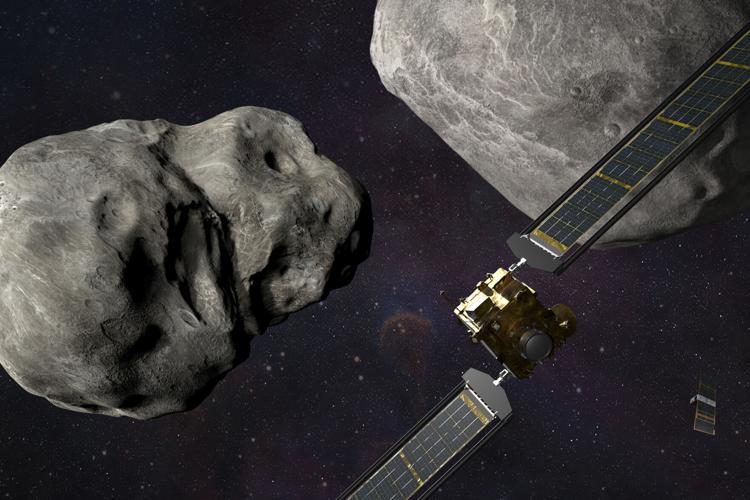

You may have seen footage of NASA’s Double Asteroid Redirection Test, or DART, hitting its target roughly 7 million miles from Earth. The fledgling planetary defense mission was designed to see if the 530-foot-wide asteroid could be redirected by a spacecraft roughly the size of a golf cart and the weight of a bull moose.

In a first for humanity, NASA smashed a vending machine-sized spacecraft into the football stadium-sized asteroid Dimorphos on Sept. 26.

“This is the first time that humans have tried to actually alter the path of an asteroid. This is the type of thing that blockbusters movies are made of!” said DART investigation team member Amanda Sickafoose.

Sickafoose is one of five scientists from the Planetary Science Institute who are working on DART. The others are Jian-Yang Li, Eric Palmer, Steven Schwartz and Jordan Steckloff, though Palmer is the only one from the global institute who lives in Arizona.

University of Arizona research scientist Melissa Brucker is on DART’s science investigation team. She also heads up the Spacewatch group at the UA’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, which was created more than 40 years ago to catalog and study small objects in the solar system.

Steward 0.9m telescope on Kitt Peak, Arizona.

“Working on this mission is very exciting,” Brucker said. “I’ve been working on near-Earth asteroid tracking for eight years, so being able to participate in the first planetary defense demonstration is a really great opportunity.”

She isn’t the university’s only link to Dimorphos.

The small asteroid orbits a much larger, half-mile-wide space rock now known as Didymos, which was discovered in 1996 by Spacewatch member Joseph Montani using a UA telescope on Kitt Peak.

The asteroid’s little moonlet, Dimorphos, was spotted and named seven years later.

Smash and grab

When they’re not knocking asteroids around, scientists with Tucson ties are busy trying to gather pieces of them to learn more about their origins and composition.

One of the best-known efforts, of course, is OSIRIS-REx, the UA-led mission that is scheduled to return to Earth just under a year from now to deliver the rocks and dust it collected from the asteroid Bennu in October 2020.

OSIRIS-REx has already involved dozens of UA scientists and students, and with about 25% of the Bennu samples destined to be studied here, the mission should continue to provide research opportunities in Tucson for decades to come.

UA planetary science professor Tom Zega is a co-investigator on OSIRIS-REx and the lead scientist for the mission’s Mineralogy and Petrology Group.

While he waits for his turn in the lab with pieces of Bennu, Zega has been studying samples from humankind’s first successful mission to collect material from a near-Earth asteroid.

On Dec. 6, 2020, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Hayabusa2 spacecraft returned a capsule to Earth containing rocks and dust from the asteroid Ryugu.

Zega said one of the Japanese mission scientists invited him to help analyze the samples, so he assembled a team that includes post-doctoral researcher Pierre-Marie Zanetta and Lunar and Planetary Laboratory alum Michelle Thompson, now a professor at Purdue University in Indiana.

They examined tiny bits of Ryugu using a transmission electron microscope in the UA’s Kuiper Materials Imaging and Characterization Facility.

Meanwhile, a trio of researchers from the Planetary Science Institute were carefully studying their own tiny portion of Hayabusa2’s precious payload at a lab at the University of Illinois.

Senior scientists Deborah Domingue, Faith Vilas and Amanda Hendrix didn’t have much to work with — just four pebbles, each no bigger than a popcorn kernel, and about 5 milligrams of fine-grain dirt and powder.

Domingue said it was awe-inspiring and a little nerve-wracking to be that close to something so tiny and so rare.

“Don’t sneeze!” she said with a laugh.

Sample sized

Analysis of the material suggests that Ryugu’s parent body formed about 2 million years after the birth of our solar system in an area much farther away from the sun than the asteroid’s present location.

The parent body eventually was broken apart by a large-scale impact and scattered inward to the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. Ryugu is believed to be made up of debris from that impact, which coalesced and moved into an orbit even closer to the sun that brings it near enough to the Earth to be considered dangerous.

“We’ve been able to trace this with some confidence,” said Domingue, who lives in Maryland but also serves as deputy director of the 50-year-old institute in Tucson. “It’s amazing what spectroscopy can tell you.”

The journal Science published their findings last week in a paper by lead author Tomoki Nakamura of Tohoku University in Japan.

For her part of the study, Domingue said she focused on the powdery grains, which were left over from earlier stress tests conducted on larger bits of the material.

She only had the asteroid samples for 10 days, and she had to pick them up herself from another researcher and then personally deliver them to the next scientist in line when she was finished.

“They were handed off to me at the Boston airport by a lab manager from Brown University,” she said.

The material was sealed inside tiny tubes that kept them from being exposed to Earth atmosphere and enclosed in a plastic carrying case about half the size of a lunchbox.

When she was done examining the stuff, she caught a flight from Illinois to Baltimore, where someone from the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory met her at the airport to take the samples off her hands.

“It was such an honor and a trust to be given any portion of this and to help analyze it. It’s really such a rare thing,” Domingue said.

The experience reminded her of when she was a kid, and she got to see a traveling exhibit featuring samples brought back from the moon by the Apollo astronauts.

“It’s like you’re touching a piece of outer space,” she said of her close encounter with traces of an asteroid. “I can’t go to outer space, so outer space came to me.”

For Star subscribers: Everyone has their own way of keeping cool during the hot summer months in Tucson. Scientist Chad Greene studies the ice sheets of Antarctica.

For Star subscribers: A study with a Tucson tie details a newly discovered asteroid impact crater beneath the bottom of the Atlantic Ocean.