When researchers shook the scientific world last year with a discovery in New Mexico that seemed to rewrite the story of humans in the Americas, they said they expected their findings to be challenged.

Those challenges have arrived.

Two new papers published within a few weeks of each other seek to cast doubt on whether fossilized human footprints unearthed at White Sands National Park are really as old as they appear to be.

In 2021, a team of 14 scientists, including two from the University of Arizona, announced proof that the footprints had been left as much as 23,000 years ago, making them by far the oldest definitive sign of human activity anywhere in the Western Hemisphere.

The new papers take aim at those findings by questioning the use of ancient ditch grass seeds embedded above and below the footprints to establish the approximate age of the tracks.

In one of the papers, scientists from Kansas State University, Oregon State University, the University of Nevada, Reno, and the Nevada-based Desert Research Institute argue that radiocarbon dating of the seeds could have been skewed by ancient groundwater deposits that would have made them seem thousands of years older than they actually are, a phenomenon known as the hard-water effect.

The second paper by a South Dakota-based scientist with the UA’s Desert Laboratory on Tumamoc Hill and researchers from New Mexico and Texas also cites the hard-water effect and argues that the ditch grass samples collected from around the footprints are unreliable because they could have been blown there from a deeper part of the lake that once covered the valley.

‘That’s science’

“That’s science,” said Kathleen Springer with a shrug.

Springer is a research geologist with the U.S. Geological Survey and a co-author of the 2021 study.

She said the White Sands team anticipated questions about the hard-water effect and sought to “preemptively address them” in the study.

“We worked really hard to make this ironclad,” she said.

But they knew there would be criticism regardless — and that the dating analysis would be the likely target — because that’s what happens “any time something is this big and this groundbreaking,” said fellow USGS research geologist Jeff Pigati.

Fossilized human footprints at what is now White Sands National Park in New Mexico. According to a new study, the tracks were left in the mud of an ancient lake as much as 23,000 years ago.

He and the rest of the White Sands team are now gathering additional evidence they hope will cement their earlier claims.

The age of the footprints could reshape what we know about the so-called “peopling of the Americas” by North Asian hunter-gatherers, widely believed to have crossed a land bridge between Siberia and Alaska during the last ice age.

According to some experts, the Clovis people were the first to arrive no more than about 13,000 years ago.

If confirmed, the discovery in New Mexico would push that arrival back by 10,000 years at least, to a time just after the Last Glacial Maximum, when a mile-high mountain of ice blocked migration into North America about 25,000 years ago.

“It really does throw a lot of what we think we know into question,” said David Rhode, a paleoecologist at the Desert Research Institute who co-authored one of the new papers. “That’s why it’s important to really nail down this age, and why we’re suggesting that we need better evidence.”

Results pending

One of the first to challenge last year’s startling study was a Tucson-based giant in the world of geology and archaeology: UA Regents Professor Emeritus C. Vance Haynes.

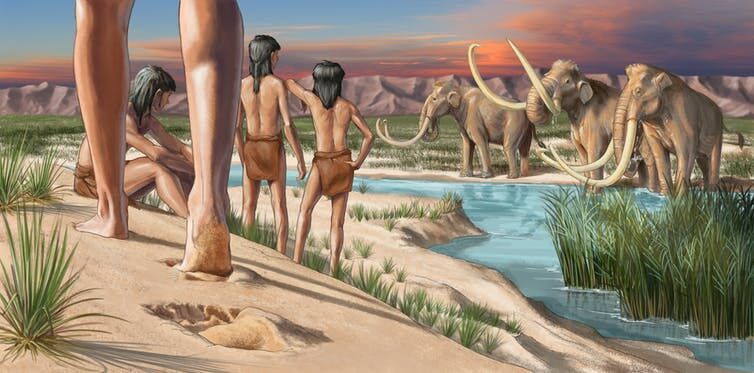

Humans share the shore with mammoths in an illustration of what White Sands, New Mexico, might have looked like about 23,000 years ago.

In an article published in March, the 94-year-old Haynes, a longtime proponent of the “Clovis-first” theory, questioned the age of both the fossilized footprints and the ditch grass seeds, as well as how the seeds came to be embedded around the tracks in the first place.

Springer said she considers Haynes a mentor and a friend, but she and Pigati joined with six other scientists to write a detailed response to Haynes’ critique in the same issue of the journal PaleoAmerica.

Meanwhile, their work continues at the White Sands site, where park resource manager David Bustos and others have identified thousands of human footprints scattered among the tracks of now-extinct ice age animals.

Springer said their trench there is now more than nine feet deep and 100 feet long. They have collected enough material from the same geological horizon as the prehistoric footprints to perform two additional kinds of age analysis.

One technique involves the radiocarbon dating of ancient pollen grains that were meticulously sifted from sediment at the site.

Pigati said the sediment had to be sent to labs in three states to isolate enough “pure pollen” for testing. Six samples, each containing about 75,000 pollen grains, are now undergoing radiocarbon analysis.

Researchers hope to receive the results in the coming days and submit a new paper on their findings for journal review by early next year.

“We’re on pins and needles,” Springer said. “We’re hoping this will be a case-closed scenario.”

Then it will be up to other researchers to figure out the larger implications of the White Sands discovery and what it says about the first human migration into North America.

“That’s on them,” Springer said with a laugh.

Added Pigati: “The archaeologists can argue about that.”

The bronze bells are still in use, so conservators cleaned and coated them to keep them ringing.