Offensive relics are being wiped off the map by the Biden administration in Arizona and elsewhere.

The U.S. Interior Department announced Thursday that 650 geographic features across the county have been relabeled to remove the derogatory and misogynistic word “squaw” from their names.

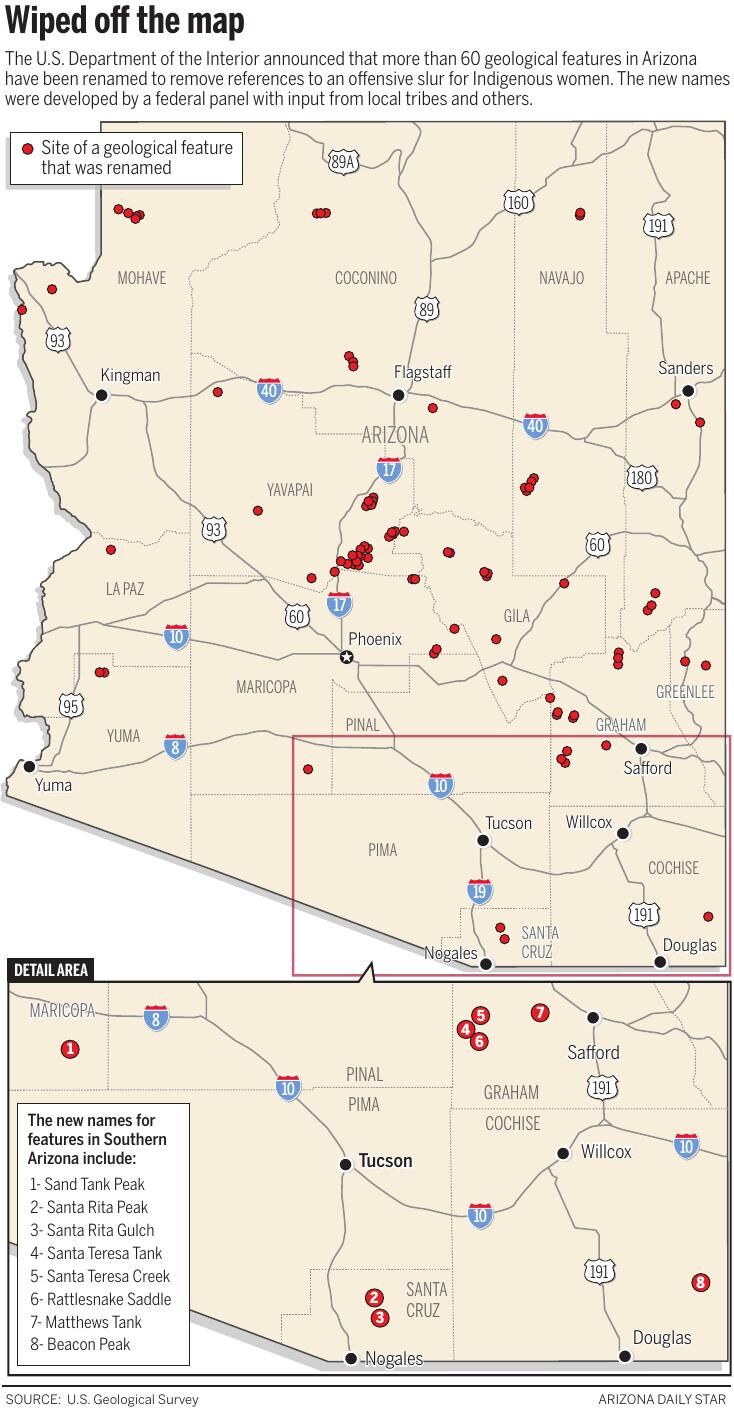

As a result, 66 canyons, creeks, peaks, springs, valleys and other sites in Arizona now have new names.

“Words matter, particularly in our work to make our nation’s public lands and waters accessible and welcoming to people of all backgrounds,” said Interior Secretary Deb Haaland in February, when the department released a list of candidate names for the various sites. “Consideration of these replacements is a big step forward in our efforts to remove derogatory terms whose expiration dates are long overdue.”

The new names were developed by a 13-member panel from eight federal agencies, in consultation with tribal representatives, local officials and others.

It will take time for the changes to show up on maps and signs, but they became official with a recent vote by the U.S. Board on Geographic Names, an executive branch office established in 1890 to track and regulate what things are called.

Arizona had the third highest number of features that needed to be renamed, behind only California with 80 and Idaho with 71.

No names were changed in Pima County. The closest sites to Tucson include a peak and a gulch at the southern end of the Santa Rita Mountains in Santa Cruz County; a creek, a reservoir and a saddle in the Galiuro Mountains in Graham County; and a peak at the edge of Sonoran Desert National Monument in Maricopa County west of Casa Grande.

A 1909 photo of the Salero Mine on the southwest slope of the Santa Rita Mountains, not far from a 5,761-foot summit that just had its offensive old name changed to Santa Rita Peak.

The 5,761-foot peak in the southern Santa Ritas, east of Tumacacori, will henceforth be known as Santa Rita Peak, and the watershed on its eastern slope will be known as Santa Rita Gulch.

The Galiuro Mountains are now home to Santa Teresa Creek, Santa Teresa Tank and Rattlesnake Saddle.

The aforementioned mountain west of Casa Grande was changed to Sand Tank Peak.

A complete list of the new names — along with an interactive map — is available online through the U.S. Geological Survey, which works in partnership with the Board on Geographic Names.

The nationwide renaming process began in November, when Haaland issued an order officially declaring “squaw” a derogatory term and directing the removal of the term “from federal usage.”

Secretarial Order 3404 cites similar efforts in the 1960s and 1970s targeting pejorative terms for Black people and Japanese people.

Arizona-born Interior Secretary Stewart Udall ordered the removal of the racial slur for Blacks in 1962, noting that “unquestionably a great many people now consider it derogatory or worse.”

The same is true of the word at the center of the current action.

“The time has come to recognize that the term ‘squaw’ is no less derogatory than others which have been identified and should also be erased from the National landscape and forever replaced,” Haaland wrote in Order 3403.

The Interior Department did not spell out the offending word in Thursday’s news release announcing the name changes, referring to it instead as “sq___.”

According to Interior officials, the term has “historically been used as an offensive ethnic, racial and sexist slur, particularly for Indigenous women.”

To oversee the task of identifying and renaming offending sites across the country, Haaland established a Derogatory Geographic Names Task Force led by the Geological Survey and made up of representatives from the bureaus of Indian Affairs, Land Management, and Safety and Environmental Enforcement; the National Park Service; the U.S. Forest Service; the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and the Office of Diversity, Inclusion and Civil Rights.

Almost 70 tribes participated in the process, which produced more than 1,000 name-change recommendations.

Before this comprehensive effort to stamp out the word, local groups and individuals had to petition the federal naming board themselves to remove it from features in their areas.

Over the past 20 years, the Board on Geographic Names has received some 261 piecemeal proposals to change the names of places because of the slur.

In 2008, the board approved a petition to rename a prominent Phoenix mountain Piestewa Peak, after Army Spc. Lori Piestewa, the first American Indian woman to die in combat while serving in the U.S. military.

In 2021, an Arizona group convinced the board to strip a particularly distasteful name from a pair of rock formations south of I-8 near Gila Bend, naming them instead after Isanaklesh, a female Apache deity whose name means Mother Earth.

And, also last year, the owners of the historic Squaw Valley ski resort, which hosted the 1960 Winter Olympics on the California side of Lake Tahoe, announced they were dropping their “racist and sexist slur” of a name.

The resort is now known as Palisades Tahoe — a change that did not require the blessing of the federal naming board, which does not concern itself with so-called “administrative” features such as schools, churches, cemeteries, hospitals, airports and ski resorts.

With her order last year, Haaland was hoping to significantly speed up and expand the name changing process nationwide.

The nation’s 54th Interior secretary is a member of the Pueblo of Laguna tribe and traces her roots in New Mexico back 35 generations. She is the first Native American to lead the Interior Department or serve as a cabinet secretary.

“I feel a deep obligation to use my platform to ensure that our public lands and waters are accessible and welcoming. That starts with removing racist and derogatory names that have graced federal locations for far too long,” Haaland said Thursday in a written statement. “Together, we are showing why representation matters and charting a path for an inclusive America.”