The National Weather Service in Tucson has unveiled a flashy new way for people to keep tabs on the monsoon season: lightning.

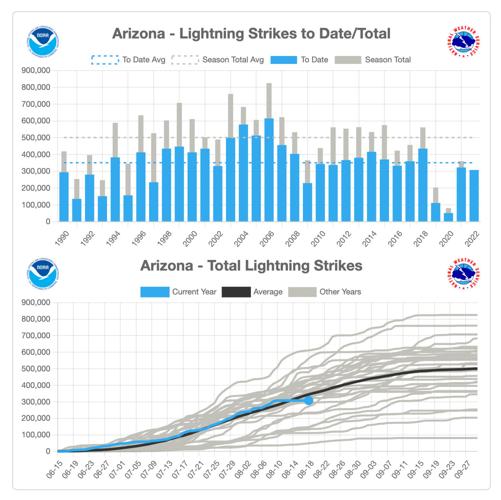

The service’s monsoon tracking website now includes a running total of lightning strikes recorded this season, along with historic data dating to 1990.

The numbers are available for the state as a whole, as well as for Tucson, Phoenix and each of Arizona’s 15 counties.

“It’s a way to capture a different element of the monsoon to see how it changes over time,” said meteorologist Kevin Strongman with the weather service in Tucson.

Tracking lightning is also a way to measure storm activity far beyond whatever rain happens to fall on the official gauge at Tucson International Airport.

“It captures a lot more,” Strongman said, and not just around populated areas, but in remote parts of the state where there aren’t any weather stations or observers.

The weather service gets its data from a Finland-based company called Vaisala, which has an office in Tucson and an advanced, worldwide network of sensors capable of recording nearly every flash of lightning across the globe.

Last year alone, Vaisala’s Global Lightning Detection Network — or GLD360 — picked up some 2.5 billion strikes worldwide, which works out to about 7 million a day on average.

Meteorologist Chris Vagasky is lightning applications manager at Vaisala’s office near Boulder, Colorado, where the company operates its National Lightning Detection Network.

He said lightning is an effective way to track the monsoon because there is a direct correlation between the two things.

“Most of the lightning that occurs in the Southwest occurs during the monsoon,” he explained. “To get a thunderstorm, you need to have moisture, instability and lift, and thunderstorms tend to produce more rain than other storms.”

In a flash

Thanks to the incredible amount of energy involved, lightning can be detected in a flash (not sorry).

Each massive electrical discharge heats the surrounding air to about 50,000 degrees — roughly five times hotter than the surface of the sun — and sends out electromagnetic waves that circle the globe at almost the speed of light.

The detection system senses the shape and direction of those waves and times their arrival to within nanoseconds, using that information to determine the precise location of a strike, how powerful it was and whether it struck the ground or went from cloud to cloud.

Vagasky said Vaisala’s network can detect a “lightning event” from more than 6,200 miles away.

With 120 sensors strategically placed around the country, the system is capable of capturing better than 99% of the roughly 25 million cloud-to-ground lightning strikes in the U.S. each year and pinpointing in seconds their location to within a football field.

The information is made available to a wide range of subscribers, from NASA to the PGA Tour.

Vagasky said the data is used for public safety, planning and investigative purposes by airlines and airports, weather services, fire departments, land management agencies, utilities, shipping companies, insurance carriers and even ski resorts, which depend on lightning data to know when it’s time to shut down lifts and get people off the slopes.

“Your airplane doesn’t move if there’s lightning in the area,” Vagasky said. “Rockets don’t launch out of Cape Canaveral if there’s lightning in the area.”

The detection data is provided in almost-real time. He said it takes about 11 seconds for a flash of lightning anywhere in the lower 48 to show up on the national network and about 35 seconds for a strike almost anywhere elsewhere to appear on the global network.

The company has cataloged several record-setting lightning events in recent years.

During a massive volcanic eruption in the South Pacific in January, Vaisala captured almost 600,000 lightning strikes above the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano in just three days. It was the most ever recorded after an eruption.

And in 2019, the company detected lightning farther north than ever before when it picked up a bolt just 30 miles from the North Pole.

Climate change is the likely culprit there, Vagasky said. The Arctic is warming far more rapidly than the rest of the globe, resulting in unprecedented storm activity in places where it has rarely if ever been seen.

“This is a new phenomenon, and it’s becoming more and more common,” he said.

Strikes down

Vaisala was founded in Finland in 1936, but the National Lightning Detection Network actually got its start in Tucson.

In 1976, three scientists from the University of Arizona — E. Philip Krider, Burt Pifer and Martin Uman — launched a research company called Lightning Location and Protection, which eventually became Global Atmospherics Inc. A decade later, they spearheaded the development of a national clearinghouse for lightning detection data.

That network was still based here in 2002, when Vaisala bought Global Atmospherics Inc. The national detection network has since been moved to the company’s office in Louisville, Colorado, between Boulder and Denver.

Through Thursday of the current monsoon season, Vaisala had detected just over 3,500 cloud-to-ground lightning strikes in the Tucson area and almost 28,000 strikes across Pima County.

That might sound like a lot, but it’s actually right in line with the overall picture for the monsoon so far in Tucson: below average.

Since the official start of the region’s rainy season on June 15, the National Weather Service has recorded just over 2 inches of rain at the airport, roughly an inch and a half less than the 30-year average for this time of year.

Lightning activity is off by a similar percentage, with 3,503 strikes recorded in Tucson through Thursday, down from the 20-year average of 5,411 by this point in the season.

Though it may not seem that way during particularly intense monsoon storms, Arizona ranks well below the national average when it comes to lightning activity.

According to Vaisala’s figures, the U.S. as a whole experiences 17.6 lightning strikes per square kilometer each year, while Arizona sees 9.3 strikes per square kilometer annually.

Greenlee County leads Arizona with 18.6 strikes per square kilometer per year, followed closely by the four other counties in the state’s southeastern corner, where monsoon activity tends to be heaviest.

Pima County ranks sixth in Arizona with 11.4 strikes per square kilometer.

The Southeastern U.S. sees more bolts than any other part of the country, led by Florida with close to 10 times more strikes by area than Arizona.

Seminole County near Orlando is the nation’s undisputed champ of lighting, with a whopping 161 strikes per square kilometer annually.

The world’s most active thunderstorm hot spots are concentrated in the warmest, wettest parts of the tropics.

No other country on Earth sees more lightning than Congo. The central African nation straddling the equator gets hit by an average of 62.5 lightning strikes per square kilometer per year, and parts of the country see double or even triple that amount.