After Tiana Reks lost her apartment seven years ago, she lived in her car. After a car crash took away her home and transportation, Reks lived wherever she could lay her head at night.

Now, Reks lives in a makeshift shelter composed of plastic tarps and plywood between a fence and a tree-lined avenue. If Tucson hadn’t declared the area she lives in along a row of about six tents a tier 2 encampment, “I have no idea what I would do,” she said.

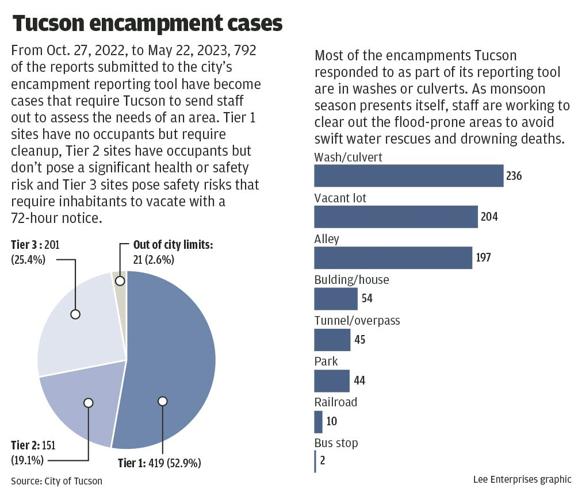

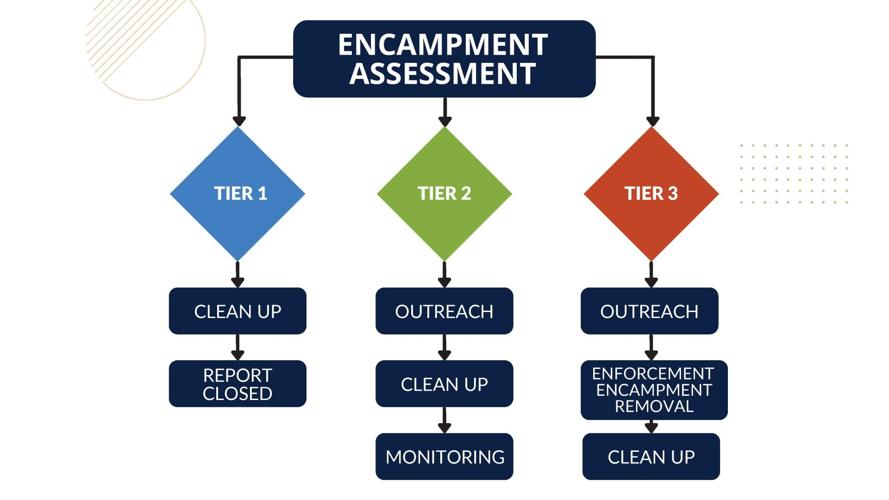

Last October, the city launched its homeless encampment reporting tool where residents can fill out an online form reporting the locations of dwellings the unsheltered population has created throughout Tucson. The city processes the report, sends outreach workers to the locations and assigns them a tiered level based on their impacts on inhabitants, the community and the environment.

Tier 1 locations are previously inhabited areas that require clean-up, while tier 2 sites have residents that are able to govern themselves and aren’t disruptive to the community. Tier 3 camps pose health and safety risks and perpetrate violence and crime toward the surrounding community and camp inhabitants, the city says. City workers provide these encampments outreach efforts for temporary shelter and wraparound social services before giving them a 72-hour notice to vacate.

Watch now: Tucson is responding to homeless encampments the community reports based on the level of danger they pose to the community. Video by Nicole Ludden/Arizona Daily Star.

Reks said she was “terrified” of being displaced from her camp, “until I found out about the whole tier thing and how we managed to get ourselves to be tier 2.”

The city brings Reks and the few other inhabitants in her encampment trash bags to keep the area clean, and she tries to let others know the camp is at capacity to keep it from growing.

“Cops will come by on their bikes and just kind of like ride through. But we don’t get told we have to leave anymore,” she said. “I’m kind of at ease at the moment, I’m not really worried about that happening. But I mean, who knows?”

Tucson’s encampment reporting tool has received 6,014 reports since it launched on Oct. 27. Of those, only 792 have become cases for in-person evaluation as of May 22, according to the city. About 54% of reports are duplicates reporting the same place and 34% are not encampments, but rather loiterers or unsheltered people temporarily seeking respite.

The tool has been key to achieving a better understanding of the transit patterns of the city’s homeless population and has allowed city workers to create a dashboard of data points for encampments and track subsequent outreach efforts. More than 15 city departments have a role in the encampment protocol.

Enhancing outreach efforts

The system has dramatically improved engagement efforts that previously operated through arbitrary emailed reports with no cohesive system to track follow-up efforts or the current status of a camp, said Justin Hamilton, a homeless encampment outreach specialist.

The tool helps the community’s businesses and neighborhoods feel like they have an active role in addressing the issue. Groups like the Tucson Crime Free Coalition have spoken out about how homelessness comes with crime and violence that threatens other’s safety and bottom lines.

But it also helps those living in encampments gain access to resources by putting outreach efforts into the hands of social workers and homelessness specialists instead of law enforcement, Hamilton said.

“It’s a fine line, because we work for the people of the city, and we work for the homeless and the unsheltered community. It’s a fine balance between trying to make everybody happy and doing what’s right,” he said. “I feel that (outreach workers) being the first eyes on, it’s better than enforcement being the first eyes on. At least now you have outreach where you’re going there to make the first initial assessment with some kind of humility right off the bat.”

Justin Hamilton, an encampment outreach specialist, right, talks about the cleanup of an alley in midtown Tucson, as Elle Millyard, encampment coordinator, listens on June 28.

Tucson’s outreach workers assign social workers to homeless individuals at encampments and get them on lists to receive housing vouchers. Workers administer a survey that assesses a person’s vulnerability and helps prioritize who receives housing assistance first. When someone’s name comes up on the list to receive a housing voucher, it’s easier to track them down through the new dashboard, Hamilton said.

The new protocol has also freed up police resources as officers play less of a role in the outreach process and public safety communications staff don’t receive as many calls reporting encampments. “We’re getting five to 10 times as much done now,” said Sgt. Jack Julsing, of the Tucson Police Department’s Homeless Outreach Team.

“The key was that we didn’t want just one department handling this, we didn’t want it to be just a 911 call where officers go there,” Julsing said. “Their tool belt isn’t as big as the entire city’s tool belt. So this whole system includes all the tool belts from all the different departments that can help.”

‘A traumatic scene’

But while some areas are allowed to remain in place, about 200 “high-problem” encampments have been disbanded under the new system, according to city data.

That includes the long-standing encampment anchored in the wash between the edge of Estevan Park near downtown Tucson and the Union Pacific railroad tracks. In the early morning hours of April 27, police cleared out the dozens of inhabitants living in tents and makeshift shelters at the camp.

The camp is uniquely positioned next to the warehouse of the Splinter Collective, a community center that provides aid to the surrounding unsheltered population. Natalie Brewster Nguyen, who co-owns the Splinter Collective center, said the encampment removal was “a deeply traumatic scene” where inhabitants were rushed out of their tents and not allowed to take all of their property with them.

“I felt like I was in the middle of a refugee camp disaster,” she said. “People were screaming and crying and fighting … People were just there with what little belongings they had left in a plastic bag or whatever they could carry. It was crazy.”

While the camp was ruled a tier 3 for violent crime and posing dangers to inhabitants and the community, Multi-Agency Resource Coordinator Amaris Vasquez said the encampment’s removal was triggered by a request from Union Pacific to clear out the area so they can start construction work on the fence neighboring the encampment. She said Union Pacific owns the land the encampment covered.

Vasquez, who coordinates homeless resources between the city and Pima County, said city workers went out to the camp many days before posting the 72-hour notice to vacate, offering residents temporary shelter opportunities and social services. She said the Environmental Services Department stores personal items collected after clean-ups at its warehouse for 30 days for people to collect.

Julsing said the camp was the setting of several violent crimes and sexual assaults, “And that’s something, as a police department, we have to address.” He said the police initiated the clean-up early in the morning to avoid higher temperatures later in the day and to allow time to clean the vast area the camp covered.

But Brewster Nguyen said the paper notices posted throughout the encampment before its removal were misconstrued as an opportunity to clean up before getting kicked out.

“People had been really, really busting their butts to try to make the camp clean under the impression that then they would not be forced to leave,” she said.

The misconception could also be rooted in previous signage posted in encampments warning of an incoming clean-up effort, Julsing said, when “no cleanup ever happened.”

“Individuals in these camps are thinking that notice doesn’t mean anything, they’re not going to do anything. But now with this efficient model that we have … when we post it, it is going to get cleaned up. And I think people are still getting used to that,” he said.

The lack of low-barrier shelter

It’s not the first time the city’s tried to clear out the Estevan Park encampment. The camp was also removed in September, according to Brewster Nguyen, who said things went a lot differently. The city clearly communicated with her they would bring vans to transport people to No-Tel, a city-run motel site used to shelter homeless people until they can find more permanent housing options.

Currently, Tucson has about 140 beds and 100 rooms across three hotels it’s purchased or temporarily leased to house the unsheltered. Unlike many of the area’s homeless shelters, there are no significant barriers to entry. People can go into the shelter with their partners and pets and aren’t required to detox from drugs.

The model is part of the city’s Housing First program, which operates by quickly moving people into housing and providing additional support services as needed. But the rooms are often at capacity and are triaged to prioritize housing for families and the elderly.

When Estevan Park’s residents had to leave in April, the city’s low-barrier housing options weren’t available. Instead, “They were offering people basically detox or Gospel Rescue Mission. And people didn’t want to do that,” Brewster Nguyen said. “Pretty much every single person said that they would happily go to the hotel if we could put them up there. Zero people were willing to go to a shelter.”

The Gospel Rescue Mission homeless shelter often has beds available, but the shelter requires residents to be sober and separates male and female partners.

The city’s housing first efforts through its low-barrier hotels have been relatively successful, according to Housing First Director Brandi Champion. Since the program began in October 2021, 678 people received shelter services and 275 were housed through the city’s non-congregate shelters as of May.

But capacity is scarce, and even if more people were to accept shelter with conditions, it wouldn’t be enough.

“We do not have enough low-barrier shelter in the community, or regular shelter for that matter,” Champion said. “If we filled every shelter bed today, we would still have homeless people on the street.”

The Tucson Pima Collaboration to End Homelessness’ point-in-time count that provides a snapshot of those experiencing homelessness on a single night grew 60% in 2023 from 2018, representing an increase of 829 people over five years.

On the night of Jan. 23, volunteers counted 2,209 people residing in a shelter, transitional housing, or living without shelter in Pima County, and 77% of homeless people were unsheltered on the night of the 2023 count.

When those displaced from tier 3 encampments aren’t allowed to return to their known residence and refuse short-term shelter, they tend to disperse and set up camp at other nearby locations.

Brewster Nguyen said the Estevan Park residents have moved to other washes and at other locations along the railroad tracks, including in a nearby underground tunnel.

“You don’t just sweep people, and then they disappear,” she said. “They’re gonna go somewhere, and they’re gonna go somewhere with way less resources than they had yesterday.”

Julsing acknowledged that this cycle is “a big issue,” but said, “We are not at functional zero, we don’t have enough affordable housing for our entire unhoused population. So that’s why when we go out, we make sure we bombard them with outreach. We may not get to you into housing this week, or this month, or even this year. But we have to get you on that list.”

More tier 3 clear-outs are set to come as encampment response workers set focus on “seasonal areas of interest.”

Of the tier 3 locations the encampment team has responded to, about 30% are located in washes and cement culverts, a number that’s expected to grow as the sweltering Tucson summer heat drives people to the cooler, often shaded locations. City staff is stepping up efforts to map encampments at risk of flooding during monsoon season. If individuals refuse to move from the washes after two outreach attempts, TPD will post a notice for the inhabitants to leave in line with the tier 3 process.

“We are going to be kind of probably a little bit more stringent because it’s a safety issue,” Julsing said. “We’ve had a lot of deaths from the unsheltered. That’s a scary thing.”

Possible solutions

Champion and other experts like Dan Ranieri — the president and CEO of social services provider La Frontera with 30 years of experience working on housing issues — say other solutions are needed, such as tiny home villages and other congregate living alternatives to standard shelters.

The model of several congregated mini-homes with wraparound services like substance abuse treatment, medical care and behavioral health support has been tested in other cities like Austin, Texas.

Ranieri said Tucson could use a similar community to shelter the homeless population that’s a “significant size” and “strategically located,” which can be difficult to accommodate with current zoning codes.

Champion said the city is consistently discussing other solutions, including tiny home communities, “in the background.”

“We’re having meetings with the people that build the buildings — the metal, congregate shelter buildings — and we’re talking about what that would look like,” she said.

But being able to leave tier 2 encampments in places like the one where Reks lives is a big step, Champion noted, as the city is “trying to keep those tier twos clean, and see how that goes.”

Reks said she would accept a hotel room from the city if offered, but she lives with a partner and dog and worries about “what would come after that.”

“People want us to get out. You know, there are so many homeless people, they need to leave or whatever. Right now, from what I understand, the homeless situation is bad,” she said, echoing the dire sentiment underlying the homelessness crisis: “Sure, there are resources, but there are only so many. And even if every shelter got filled, there wouldn’t be enough.”