An internal financial document obtained by the Arizona Daily Star shows that the University of Arizona spent about $125 million more than it made this past fiscal year.

The document, which includes a breakdown of every unit within the UA, has financial information from fiscal years 2019 through 2023.

According to UA spokeswoman Pam Scott, the report’s “primary purpose is to show whether units are spending more or less than the resources provided, whether they are maintaining or using reserves, and if they are using reserves, how rapidly and consistently they are using them.”

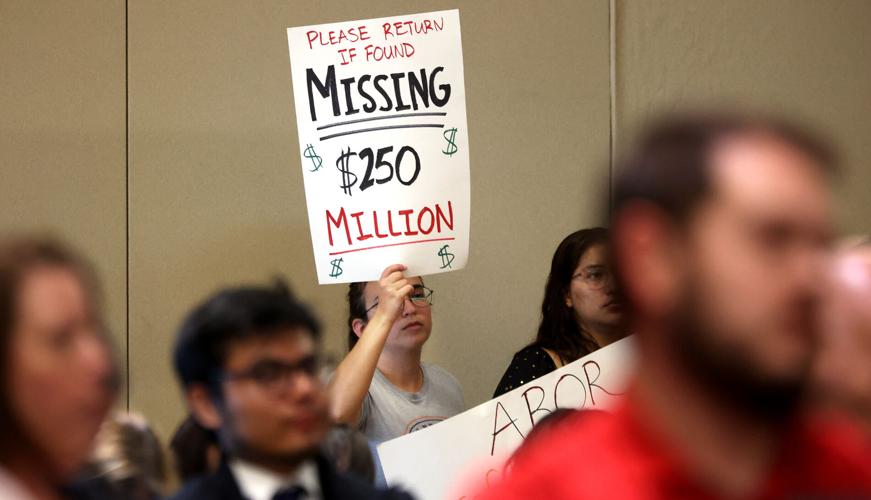

The business affairs office oversaw overspending of a combined $14 million. That unit, which is led by the university’s Senior Vice President for Business Affairs and Chief Financial Officer Lisa Rulney, was the one responsible for the $240 million miscalculation of projected cash reserves that has led the university into its current financial crisis.

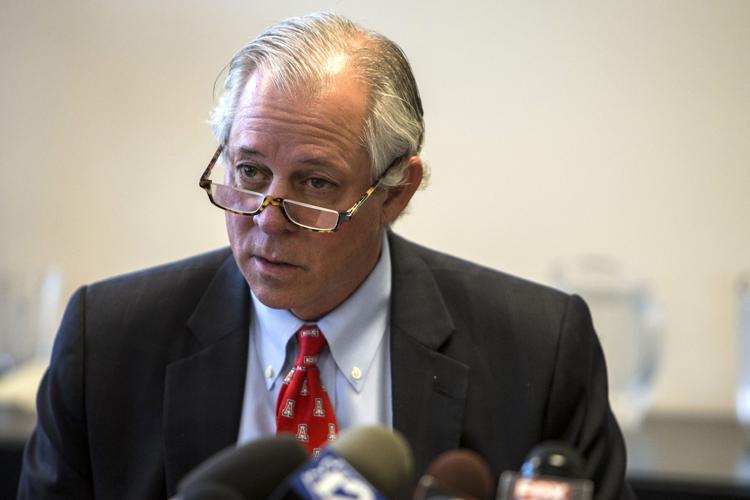

University President Robert C. Robbins’ own executive office of the president overspent by $1.655 million this past year.

UA President Robert C. Robbins' executive office of the president overspent by $1.655 million this past fiscal year, according to an internal financial document obtained by the Arizona Daily Star.

All of the colleges within the university overspent by a combined $43 million, though faculty members have spoken out and blamed extreme taxing by central administration and the UA spending more on athletics and strategic initiatives instead of funding the colleges as it normally does.

“Academic mission revenues have funded nearly $87M of unrecovered internal loans to the athletics department over the last five years,” Leila Hudson, president of the UA Faculty Senate, wrote in a message to all faculty members on Dec. 1. “In 2023 alone, according to President Robbins, our academic work subsidized $31M of unrepayable ‘loans’ to athletics.”

- Colleges are the university's academic, research, and service providers.

- Support units are the central administrative units supporting the overall university. They include support activities such as human resources, facilities management, and information technology.

- Auxiliary units are largely self-supporting units that generate revenues as additional services are provided to students or the community, such as the bookstore, student union, housing, and athletics.

- Institutional units hold costs supporting the entire university, like utilities and insurance but are also used to record revenues and allocate resources distributed throughout the university.

Hudson’s statement is backed up by a note in the financial document that states revenue listed for the athletics department included “internal loans of $86.6 million.”

Previously, Robbins stated that the university loaned $55 million to the athletics department during the COVID-19 pandemic, though this internal document suggests the figure is closer to $90 million. Robbins confirmed the number is $86.6 million in Monday’s Faculty Senate meeting.

In that faculty meeting, Robbins said that there will be layoffs in the athletics department this year. Additionally, he said season ticket prices for football and basketball will rise by 25%, while general ticket costs across the board are also expected to increase.

“Athletics, they are cutting, they are firing people, they are laying off 100%,” he said. “They are laying off people in order to increase revenue.”

Rulney

Robbins acknowledged that “several colleges” have a lot of administrators with fewer students and told faculty that budget cuts will disproportionately impact administration in an effort to promote equity.

The number of administrators hired since 2018 has increased by 26.8%, while the number of tenure and tenure-track faculty has decreased by 5.7%, according to a document shared at the faculty meeting by Russell Witte, a professor of medical engineering.

Robbins did not confirm if there would be layoffs in other units, saying that will likely be a decision based on each college or administrative unit.

“I think it’s going to be to each of the unit managers to decide about how to manage their budget,” he said. “I don’t foresee a, you know, 5% layoff of all employees.”

Understanding the data

Because the spreadsheet was only meant to be shared internally, some of the numbers are inflated, or double counted, according to those familiar with the document.

Grants, contracts and philanthropic gifts are not a part of the spreadsheet, and because it includes transfers between internal units within the university, some of the transactions are essentially counted twice. This means that, in the document, the total budget of the university is about $3.5 billion, when in reality it is about a billion dollars less than that.

“These movements of funds are recorded as both ‘revenues’ and ‘expenditures’ in this report, thus inflating real revenues that one would find in external reporting, such as those presented in our Annual Comprehensive Financial Reports,” UA spokeswoman Scott said.

The biggest deficit on the spreadsheet, from the business affairs general section, is $31.8 million. The business affairs general unit, according to those familiar with the document, represents a budget clearing unit that distributes revenues, such as tuition and state appropriations, across units and covers institution-wide costs. The business affairs general unit does not hold any employees.

“This division holds reserves, which help support the entire institution’s reported balances,” Scott said of the business affairs general unit. “Those reserves have been invested primarily through strategic plan initiatives and other priorities of the president and executive leadership.”

Breakdown of colleges’ spending

There are 16 colleges categorized under “main campus” in the spreadsheet. Of those, 11 spent more money than they made in fiscal year 2023.

The James E Rogers College of Law has consistently operated in a deficit each year since 2019, according to the document. In 2019, the college entered a deficit of $510,587 after spending $932,657 more than it took in.

In 2020 the Rogers College of Law’s gap between expenditures and revenue was $2.04 million, in 2021 $445,436, in 2022 $3.46 million and in 2023 it hit its highest of $5.38 million.

Currently, according to the document, the college is in a deficit of $11.8 million.

A graduating class of the UA James E. Rogers College of Law. The College of Law has consistently operated in a deficit each year since 2019, according to the internal financial document. UA President Robert C. Robbins told the Star the law school has been "given permission to operate in a deficit."

Interestingly enough, Rulney said in Monday’s Faculty Senate meeting that “we don’t approve plans unless the budget is breaking or positive,” adding that her office doesn’t let colleges “plan to spend into deficit.”

Robbins told the Arizona Daily Star that the law school has been “given permission to operate in a deficit,” though he did not elaborate on what the circumstances or reason of that approval were.

The Forbes Building, home to the UA College of Agriculture, Life and Environmental Sciences. The college spent $19.5 million more than it made in 2023. Leaders within the college claim spending was at the direction of UA Chief Financial Officer Lisa Rulney. Rulney counters that her office doesn't let colleges "plan to spend into deficit."

The College of Agriculture, Life and Environmental Sciences spent $19.5 million more than it made in 2023. As previously reported by the Arizona Daily Star, leaders within the college claim the spending was at the direction of Rulney, the university’s chief financial officer. The college still has $10.85 million cash on hand because it turned a profit in 2019, 2020 and 2021.

The College of Architecture Planning and Architecture Design spent $1.14 million more than it made in 2023. It ended 2023 with $4.46 million in its fund balance.

Despite previously spending more than it took in in 2019, 2020 and 2022, the Eller College of Management turned a profit in 2023. The college made $1.27 million this year and ended the fiscal year $3.34 million in its fund balance.

The College of Education spent $3.8 million more than it took in this year. It’s avoiding a deficit by ending the year with a fund balance of $304,476.

The College of Fine Arts also recorded spending more than it earned, which it hadn’t done in 2019, 2020, 2021 or 2022. For the first time in the dataset, the college spent more, $1.94 million, than it made. It finished the year with a fund balance of $9 million. .

Similarly, the Graduate College reported its first overspending in the dataset, as well. Despite turning a profit in 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022, the college spent $629,708 more than it made in 2023. Its fund balance currently sits at $4.09 million.

The College of Humanities made $1.5 million more than it spent in 2023. It ended the fiscal year with a fund balance of $19 million.

The W.A. Franke Honors College also turned a profit this year. It made $402,729 more than it spent in 2023. The college currently has $402,749 in its fund.

The iSchool once again spent more this year, by $1.3 million, than it brought in. Currently, it is in a deficit of $699,305.

The James C Wyant College of Optical Science made $2.79 million more than it spent this year. It has an end fund balance of $14.5 million.

The College of Social and Behavioral Science reported its second time spending more than it made in two years. The college spent $8.39 million more than it made in 2023. It ended the year with a fund balance of $20.9 million.

For the third time since 2019, the College of Science spent more, $8.39 million, than it took in this year. Its fund balance stands at $2.5 million.

The College of Applied Science and Technology, like most of the other colleges, spent more than it took in this year. This time, it spent $1.3 million more than it earned. Its end fund balance is currently $6.59 million.

An audience member holds up a sign about the University of Arizona’s $240 million miscalculation in projected cash reserves at a recent Arizona Board of Regents meeting.

The College of Veterinary Medicine turned a profit once again. The only loss it reported was in 2020, when it entered a brief deficit. This year, the college made $4.57 million more than it spent. The college reported that its fund balance is $11.9 million.

The health sciences colleges have done relatively well. This year the colleges combined, which include the Arizona health science centers and divisions, the College of Medicine in Phoenix, the College of Medicine in Tucson, the College of Nursing, the College of Public Health and the R. Ken Coit College of Pharmacy, spent more than they made by just $549,761.

During the years of 2019, 2020, 2021 and 2022 the health sciences colleges combined made more than they spent, making this year an outlier in the data.

The colleges within the group that spent more than they took in are the College of Medicine in Phoenix which spent $1.1 million more than it took in, the College of Public Health, which spent $2.36 million more than it took in and the Coit College of Pharmacy which spent $3.13 million more than it took in.

How did this happen?

According to Hudson and other faculty members who spoke to the Star, the colleges struggled financially because the university stopped reinvesting as much as it usually did.

The UA recently switched from a budgeting tool called Responsibility Centered Management, also known as RCM, to Activity Informed Budgeting, shortened to AIB. Though many in faculty leadership acknowledged there were flaws in RCM, AIB is much worse, they said.

Under AIB, the university taxes revenue from the colleges into a central account. Senior leadership has control over that account and can choose to spend those taxed dollars on anything, including reinvestment into the colleges or special, more expensive projects.

Critics of the model say the UA has irresponsibly spent from the central reserve of taxed money without properly reinvesting in the academic units.

“The big problem with these budgeting systems is that there’s no internal regulations on central administration’s spending,” said Gary Rhoades, an education professor who serves as the chair of the general faculty financial recalibration committee.

Additionally, colleges earn certain dollar amounts for teaching students and having students major in their departments. Under both RCM and AIB, colleges make about the same money per student once that student graduates. The big difference between RCM and AIB is in year-to-year totals.

Though it evens out by the end, colleges are currently in an initial shock period, losing out on 25% of revenue they expected to get under RCM. Only when a student graduates do colleges get the big payout they need. So, currently, and until about four to five years from now when colleges will continually earn that big payout from graduating majors, they’re in big trouble.

This is, of course, heavily impacted by the university’s current financial crisis. A fiscally healthy university might be able to use more of the revenue taxed from colleges to reinvest in those colleges and help ease the transition from RCM to AIB.

The UA, however, has implemented a 2% budget cut and is expected to announce more money-saving maneuvers in a report Robbins must make to the Arizona Board of Regents by Dec. 15. Because of these circumstances, the university is less likely to reinvest significant swaths of money into the colleges, meaning many are trying to prepare for a financially bumpy few years.

Another negative of AIB, critics argue, is that colleges which teach heavy loads of “service courses,” or general education requirements, are making much less money than under RCM. This means that most colleges that teach lots of these “service courses” won’t recover from the switch until they change their course options. Popular classes that fall under this category include Introduction to Chemistry and Communications 101.

Central administration has committed to providing initial monetary support to colleges to help ease into the new system but will reduce that support by a whopping 5% each year. This means that the vast majority of colleges must grow by 5% each year in order to be financially stable.

That’s a tough ask.

Hudson said the AIB budgeting model “withholds effectively the last mile” of funding that many colleges rely on. It’s causing colleges and departments to hire mainly adjunct professors instead of tenure and tenure-track positions.

In fact, many faculty members including Hudson and Rhoades say part of the reason the UA is in a financial crisis is from the implementation of AIB in 2022.

Rhoades compared faculty members to “worker bees” in his description of the budgeting model.

“We’re producing more, we have more students, we’re teaching more classes, and we get more grants, but we get less money,” he said. “That money we get less of goes to the center and then they overspend it.”

Breakdown of admin, staff spending

The human resources division spent about $796,000 more than it took in this year and ended the year with a fund balance of just over $4 million.

The new division of Black Advancement and Engagement spent about $53,000 more than it took in, ending the year in a small deficit of $53,172. The division of Hispanic Serving Institution, which is also relatively new, spent about the same amount more than it took in, ending the year with a fund balance of $179,000. The diversity and inclusion unit spent $183,648 more than it took in this year and ended with a fund balance of $2.143 million.

The total provost support units ended up making about $5.3 million more than they spent this year, ending the year with a fund balance of $72.8 million. The units within the provost support division that were profitable include the Undergraduate Education unit, the Student Success Retention Innovation unit, Arizona Online and Distance, Arizona Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension. Those within the provost support division that spent more than they made were the Academic Affairs division, Academic Administration, the Vice Provost Academic Affairs division, Campus Life Administration, the Dean of Students office, the Disability Resource Center, enrollment services and libraries. In total, provost support units ended the year with a fund balance of $72.8 million.

The Office of Campus Safety spent a combined $149,000 more than they made this year. The Risk Management and Safety Division spent $71,145 more than it made, while the university’s police department spent $77,800 more than it made.

The Office of the General Counsel spent $51,000 more than it made this year, with an end fund balance of just under $900,000.

The business affairs support units in total spent $7.5 million more than they made this year, ending with a fund balance of $34.7 million. The units within the division that were profitable this year were the Business Affairs Shared Services office, the Financial Services office, the new Finance Strategy and Solutions unit, the Internal Audit unit and something called “planning and operations Phoenix.” Those that spent more than they made were the Division of Sustainability, the Planning Design and Construction unit, Facilities Management, the Business Affairs division, and the division of Budget and Planning.

Research Support made a total of $1.1 million more than it spent this year, ending the year with a fund balance of $39.7 million. Profitable units in the division include Tech Launch Arizona, Tech Parks Division (which overcame a deficit this year) and RII Research Infrastructure. Those units that spent more than they made were the RII Museums Division and RII Centers and Institutes.

The Alumni and Development division spent just under $100,000 more than it made, ending with a fund balance of just over $7 million. The Marketing and Communications division spent $733,000 more than it made this year, ending the year with a fund balance of $3.2 million.

The division of Native American Advancement made $617,000 this year, with an end fund balance of just over $1 million. Over three years, the division has grown from an end fund balance of $73,000 to $1 million.

Within the “Secretary” units, the University Compliance Division made $336,00 more than it spent, the Division of Secretary of the University made $588,000 more than it spent, and the University Information Tech Services Division spent just under $5.5 million more than it made. The units ended the year with a combined end fund balance of $16.2 million.

The general Academic Affairs unit turned a profit of $2.3 million, ending the year with $26.2 million in its fund balance, while the Institutional Research division made about $500,000 and ended the year with $8.3 million in its fund balance.

The provost’s auxiliary units spent a total of $2.6 million more than they made this year. Campus Health and Wellness, Housing and Residential Life, and Campus Recreation all contributed to that spending, while Arts Presenting and Engagement made about $1.6 more than it spent this year. The provost’s auxiliary units ended with a combined $37.5 million in fund balance.

Finally, the business affairs units spent a total of $6.3 million more than they earned this year. Student Unions and the UA Association Students Bookstore both spent more than they made, while Arizona Public Media and Parking and Transportation turned a profit. The group is ending out the year with a fund balance of $8 million.

“We thought the future was gonna be brighter as a member of the Big 12. … I think this is a very exciting deal for us.” — Arizona president Robert Robbins; Video by Justin Spears/Arizona Daily Star