Steve Minarik was the last of the three Minarik siblings to be diagnosed with early onset familial Alzheimer’s disease.

He was 43 years old. His children were 10 and 12.

“Even though both of us were expecting it, it did not make the news any less devastating,” his wife, Sheryl Stephens Minarik, said. “Driving home from that appointment was gut-wrenching and tear-filled.”

Steve was diagnosed on Feb. 2, 2009. He died on July 27, 2015.

Jogging shorts with cowboy boots

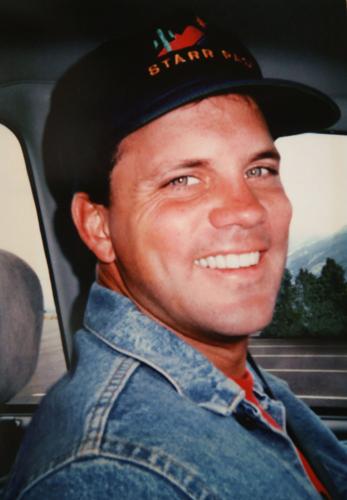

Born in 1965, Steve was an avid baseball player who loved golf, big-band music and his family. He was popular, social and good looking, with the same striking blue eyes as his father and two sisters. He played trumpet in the Santa Rita High School band, and especially loved the 1812 Overture.

Steve met his future wife Sheryl at the University of Arizona when both were earning their bachelor’s degrees in education and were student teachers at Amphitheater High School. Before they dated, Sheryl invited Steve to happy hour and asked him to wear his cowboy boots with his Levi’s 501 jeans and polo shirt because he looked so good in them. But when Steve turned up at the bar, he was wearing a crisp white shirt with tiny jogging shorts, tube socks and his cowboy boots.

“I’ve got my boots on!” he exclaimed as he walked in.

Her friends thought it was hilarious, but Sheryl wanted to crawl under the bar. Ultimately, watching him with his nieces and nephews won her over.

When he arrived at his sister Cheryl and brother-in-law Mark’s house, the kids would run out the door yelling, “Unca Steve! Unca Steve!” Steve crouched down and opened his arms wide.

Then, and for the rest of his life, his biggest love was his family. “That was it for him,” Sheryl said. “Family made him very content.”

When she and Steve were just starting out together, Sheryl knew there was “something in his family” but no one said much about the disease that had killed Steve’s father, grandmother and great-grandmother. It turned out to be early-onset familial Alzheimer’s disease. Everyone in Steve’s gene pool has a 50-50 chance of inheriting the mutation that causes it — and virtually everyone with the mutation gets the disease.

“I really didn’t pay much attention to the Alzheimer’s. People did ask, and they’d ask if I was worried, but what was I going to do?” Sheryl said. “I loved him, I wanted to marry him, and it seemed a remote possibility that he’d ever get sick.”

The couple married in 1993 and they taught school and lived in Tucson for several years — Steve at Flowing Wells High School and Sheryl at Tortolita Junior High School. Then Sheryl took eight years off when the couple had their sons, born in 1996 and 1998.

“Steve worked his tail off, literally,” Sheryl said. “He was never afraid to work hard and told me to just resign and that he would find more work. At the time, I cut our income exactly in half and I think we were both making about $28,000. But Steve was undaunted and believed that my staying home was important.”

When Sheryl eulogized her husband last year, she recalled how Steve worked lunch duty because he got paid and received free lunch, sponsored an after-school chess club, taught night courses and coached, all while working toward his master’s degree in educational leadership from Northern Arizona University. He graduated in 1997 with a perfect 4.0 grade-point average.

“Not once during the eight years that I was home with the kids did Steve ever question me about what I did all day, where I was spending money, why the house wasn’t cleaner,” Sheryl said. “I can honestly say that he always came straight home from work with a positive attitude, even though he may have been apprehensive about what he might find.”

In 2005 the family moved to South Korea, where both Sheryl and Steve taught for two years. He taught computer skills and at one time had both of his own children in his class.

Letter of reprimand brings a fit of panic

At first, the signs were subtle. Steve was forever misplacing his wallet.

But one day in 2007, after the family had moved to Prescott Valley and set about finding a house to buy, Sheryl mentioned a brown house they’d seen and Steve became quiet. Then he started to cry.

“I don’t know what house you are talking about,” he said. “What are we going to do if I have Alzheimer’s disease?”

Sheryl started crying, too.

“I’ll take care of you,” she said.

Steve’s first job in Prescott Valley was teaching high school economics, a subject he’d never taught before. He was working all the time and seemed overwhelmed. Sheryl was relieved when he got a job teaching social studies for the 2008-09 school year, because he loved history. Maybe things would get better. But on Labor Day weekend at the beginning of school, he suddenly began weeping.

“I thought I was going to throw up,” Sheryl said. “Steve was really depressed, lost a lot of weight and really just stopped communicating with us. Thankfully, the kids don’t remember that.”

Sheryl and Steve’s mother, Mary Kay, clung to the best-case scenario: depression. Steve went on an antidepressant and, for a while, it helped. Throughout that semester, Sheryl went to school with her husband every Sunday to help him get organized.

“I was trying to pretend everything was all right with my kids,” she said. “I would ask him, ‘How is school?’ He would always say, ‘It’s OK.’”

But over Christmas break Sheryl discovered a letter of reprimand in Steve’s backpack that said if he didn’t improve in 90 days, his contract would not be renewed.

Sheryl panicked. She called Mary Kay and they made an appointment with University of Arizona neurologist Dr. Geoffrey L. Ahern, who had also treated Steve’s sister Beth.

After some cognitive testing and a blood test, Ahern delivered the bad news. The next day was Steve’s last day of teaching.

At dismal end, he’s unable to swallow

For several years, Steve seemed to be on a plateau. The family got a golden retriever named Boomer and Steve walked the dog five or six times per day.

“Boomer kept Steve content and busy for quite a long time,” Sheryl said.

Their dad’s decline was difficult for the boys. At least once Steve had a bowel movement and missed the toilet. One of the boys cleaned it up before Sheryl got home.

Steve declined to a point where Sheryl no longer felt safe leaving him alone. First he went into adult day care, and the following year, a few months after his sister Beth died of Alzheimer’s, the family felt he needed something full time.

On Sept. 1, 2014, he moved into Pacifica in Tucson, where Beth had lived for several years.

There, he would ask, ‘Why am I here?’” and he would holler and cry. He progressed to where he couldn’t feed himself. One night he destroyed his room at Pacifica, and pulled the toilet out of the floor.

Eventually, Steve couldn’t walk or swallow. Like she had done with Beth, his mother rented a hospital bed and put it in her guest bedroom. Steve lived another week.

Immanuel Presbyterian Church was packed for Steve’s funeral.

“He faced each day as positively as he could and participated in life as fully as he could: driving until he could not, going to all sporting events until he could not, taking care of our dog until he could not, enjoying vacations until he could not, and finally living until he could not,” his wife told mourners. “What greater example of courage is there?”

When Steve died, the family asked for donations to early-onset familial Alzheimer’s research at the Banner Alzheimer’s Institute in Phoenix. Like they had done with Beth, they donated Steve’s brain for an Arizona-based Alzheimer’s research study funded by the National Institute of Aging.

When Steve died, his surviving sister, Cheryl, said she was relieved her brother was no longer suffering. Around that same time, Cheryl’s own Alzheimer’s symptoms began to progress.