Smith “Smitty” Minarik had a signature honk of his car horn — three blasts to say “I love you.”

Born in 1937 in Tucson, Smitty was a softie — the opposite of his tough-guy father. Frank Minarik, a local civic leader and real estate broker, was West Coast campaign manager during his college roommate Estes Kafauver‘s bid for the Democratic presidential nomination in 1952.

A photo in the Arizona Daily Star archives shows Frank, then chairman of the Pima County Democratic Party, riding in a car with presidential candidate John F. Kennedy in Tucson in April 1960.

After Frank married Clarabel Smith and moved to Tucson in 1925, the couple purchased 30 acres at Pima and Wilmot and built a home. Clarabel died at age 46 and Frank, strong and opinionated, raised his three children — Smitty, Mary and Clara Joe — on his own.

Smitty was 9 when his mother died, and he grew up not knowing exactly why. He thought maybe her mental problems stemmed from hardening of the arteries, or perhaps diabetes.

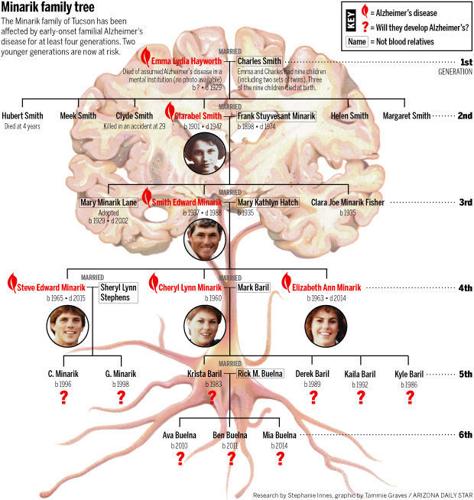

The family knows little family history before Clarabel, though one of Smitty’s sisters recently discovered that Clarabel’s mother, Emma Lydia Hayworth Smith, died in a mental institution, too. The family now believes both Emma and Clarabel had the devastating early-onset familial Alzheimer’s that is part of the Minarik family bloodline.

After graduating from Tucson High in 1955, Smitty went to Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas, where he met Mary Kathlyn Hatch. The two married in 1959 in Breckenridge, Texas, two weeks before Mary Kay, as she was known, turned 20. Smitty, 22 at the time, had just graduated with a major in government and history. As was common in those days, Mary Kay left school when they married.

“We knew when we married that there was something in the family that happened to women around menopause,” said Mary Kay. “But we had no clue there was Alzheimer’s in the family. We didn’t talk about Clarabel. It was sort of a taboo subject.”

Everybody knew what three dots meant

After completing a commission in the U.S. Army Reserves, Smitty settled with Mary Kay on Tucson’s east side. He began teaching high school, ultimately landing at Palo Verde High School as a social studies teacher.

With his sport coat, Smitty wore wide ties made by his aunt Markie in New Jersey. They were loud — a bright pink and chartreuse Hawaiian print, a blue one with Superman on it. He liked to make his students laugh.

And he liked to show his family love. When Mary Kay or the kids would rip a paper towel from the dispenser they’d occasionally find, “I love you” written by Smitty. He frequently wrote those same three words in the snow outside the Minarik family cabin on Mount Lemmon. Sometimes he’d leave a note with just three dots on it — and they all what knew it meant. “I love you.”

“Smitty was soft, loving, and he played with the kids,” Mary Kay said. “I was always the disciplinarian.”

The family wasn’t watching for signs of Alzheimer’s in Smitty because they had no reason to think he was at risk. Back then, they didn’t have a name for what had afflicted Clarabel — and they believed it only went after women. One of Smitty’s sisters was adopted, so they didn’t worry about her. There was some concern about his biological sister, Clara Joe, but it turned out she did not inherit the genetic mutation.

Frank died in 1974 when Smitty was 37. A few years later, Smitty started asking Mary Kay questions she’d already answered, such as where they were going to dinner. He’d ask the same question two or three times within an hour.

It’s difficult to pinpoint exactly when Smitty’s symptoms began because early stages of Alzheimer’s often look like absentmindedness. The disease tends to start depositing plaques and tangles in the temporal lobe, which deals with memory and language.

With Smitty, the symptoms looked like a prolonged depression.

Bills go unpaid and the mind drifts

Not knowing what was wrong, Smitty and Mary Kay went to a Marriage Encounter weekend through their church. It was a disaster. The leader asked them to write letters to one another; Smitty could not stay on topic.

Then Mary Kay found out that Smitty had not been recording grades all year. The family’s finances were in shambles — property and income taxes had gone unpaid, and Smitty had been taking bills from the mailbox but not paying them. Palo Verde High School put him on medical leave.

By 1980, doctors had a diagnosis.

“I’d never heard of it,” Mary Kay said. “Alzheimer’s. It was a new word to me.”

Alzheimer’s disease was named in 1910 for a German psychiatrist named Dr. Aloysius “Alois” Alzheimer, who first noticed the disease in a patient in 1906. The patient had profound memory loss and when she died, Alzheimer noticed her brain was shrunken and had unusual deposits in and around the nerve cells. Those deposits would later be identified as beta amyloid.

But when Smitty was diagnosed, not many people were talking about Alzheimer’s.

He asked Mary Kay whether he was going to die.

“I said, ‘Yes, but not any time soon,’” Mary Kay recalled. “We acted like nothing was wrong. We just told him he had depression problems. He never made a fuss.”

Unable to work, Smitty began to run, going miles and miles near his home. He continued to get up early every morning — at 5 or 5:30 — as he’d done his whole life. He’d get the newspaper and coffee and, weather permitting, enjoy them outside. He continued to drive, though Mary Kay monitored him and never let him go far.

Occasionally his disease would cause problems, like when solicitors would knock on the front door asking for donations. Smitty invariably gave away more than the family could afford. His two younger children were still in high school and Steve was sometimes embarrassed by his father. Unsure of what he’d do or say, his son didn’t really want him at his baseball games.

Smitty makes a U-turn and disappears

In 1982, Smitty beamed as he walked his eldest daughter, Cheryl, down the aisle of Christ Presbyterian Church at her marriage to Mark Baril.

“He was very, very happy that day,” Mark remembers.

When they did yardwork together, Smitty would tell Mark that “a lazy man works himself to death,” meaning it’s better to do all the work, no matter how difficult, than to take shortcuts. Shortcuts will catch up to you.

He never seemed to have a down day, and he enjoyed the little things, like eating apples — every last bit of them.

“If you didn’t eat your core, he’d frown on you,” Mark said.

Then one day in 1983, Smitty went missing.

He had gone with Mary Kay to pick up her car at the mechanic’s and they drove home separately, with Smitty following his wife.

“He made a U-turn and disappeared,” Mary Kay said. “We had half the church looking for him.”

Eventually Mary Kay got a call from a police officer. He’d found Smitty driving about 5 mph on a dirt road near the airport, crying. A friend drove Mary Kay to where he was waiting with the police.

“I’m so sorry,” he told his wife.

He never drove again.

Didn’t know where he was but “having a ball”

As Alzheimer’s progresses, the plaques and tangles in the brain tend to build up in areas associated with thinking and cognition, including the parietal lobe, which handles information about space, place and movement.

Damage to this lobe can cause people to feel lost even when they are in places that were once familiar.

As a result, people with Alzheimer’s disease often react poorly to change and like to stay in the same place.

That was not true for Smitty, who traveled throughout most of his illness.

“Smitty always wanted to be where I was. I was his anchor,” Mary Kay said.

Three years before he died, they went to Europe for a month with two other couples.

“He didn’t know where he was but he was happy as a clam. He was having a ball,” Mary Kay said. “Everyone knew you had to watch for him.”

The year before he died, the couple went on a raft trip down the Grand Canyon with friends. Then a few months later, Mary Kay tried taking him on a road trip through California with her parents. He pounded on the windows as though he was being kidnapped.

Mary Kay turned the car around.

Smitty’s downward slide had begun and it quickly picked up momentum. He shortened his runs, eventually to just the corner and back. Then he quit.

“He was afraid to get lost, I think,” Mary Kay said.

Their granddaughter Krista Baril Buelna was born in 1983 and remembers Smitty sitting on the floor with her as she played with a new Barbie house she got for Christmas. She mostly remembers her grandmother taking care of him, and how Mary Kay would buy her a Kit Kat every time they went to the medical supply store.

Mary Kay changed Smitty’s diapers, cut his food and never left him by himself. At the end, Smitty began having seizures and was increasingly confused. He also had uncharacteristic bouts of anger.

When he pulled a fire extinguisher off the wall and threw it while at an adult day program, he was asked not to return. Walking became difficult and when he fell, Mary Kay was unable to pull him back up on her own.

Mary Kay found a neighborhood group home, and that’s where Smitty spent the last six weeks of his life.

Alzheimer’s disease leaves people so debilitated that they are increasingly susceptible to infections and illness. So it’s not technically the Alzheimer’s that kills them, but really, Mary Kay says, it is.

Smitty died of pneumonia on Oct. 19, 1988, at age 51.

Mary Kay donated his brain to the University of California at San Diego. Researchers there confirmed the Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

As the hearse pulled away from the cemetery after his burial, Mary Kay asked the driver to honk the horn three times.