When the OSIRIS-REx spacecraft delivers its precious asteroid samples to Earth on Sept. 24, two University of Arizona researchers will be among the first to examine the scientific treasure trove.

Professor Thomas Zega and assistant professor Pierre Haenecour from the UA’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory are part of NASA’s “quick-look team,” a small group of researchers assigned to conduct the first science on what the spacecraft collected from the asteroid Bennu.

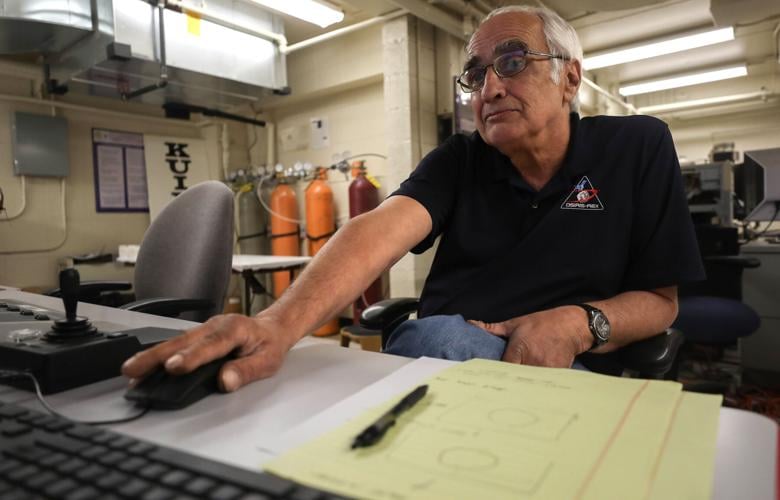

“I get goosebumps just thinking about how I will be among the first people in the world to actually see the sample — not just see it, but analyze it in detail,” said Zega, who arrived at the UA in 2011, the same year NASA approved the university’s now-$1 billion asteroid sampling mission. “We will know ahead of even the science team what’s in the sample.”

But they won’t have much free time to marvel at what they are seeing. The team will be on a tight, three-day schedule to collect the first images and measurements that NASA plans to release to the public soon after.

Haenecour said they are tasked with conducting “the really initial characterization of what the sample looks like and what it is composed of.”

The University of Arizona-led OSIRIS-REx asteroid sampling mission gets a trailer fit for a Hollywood blockbuster, courtesy of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center.

“It’s really exciting to be among the first to put it under a microscope and get the first image to see what it actually looks like,” he said. “We expect to be surprised.”

They won’t have a lot of material to work with, either.

Haenecour said they expect to get roughly 100 milligrams of asteroid particles that stuck to the outside of the spacecraft’s sampling device when it touched down on Bennu on Oct. 20, 2020. That’s about 2% of a teaspoon.

“They’re going to just wipe some dust that was basically outside of the actual sample canister, put it in a vial and give it to us,” he said. “Then we have three days to do our suite of measurements to provide the initial characterization while they’re opening the canister.”

Rush job

Luckily, Zega said, “we’ve gotten really good at what you might call micro-sampling.”

Even a single speck of dust measuring just 20 microns across — roughly one-quarter the thickness of a human hair — can now be delicately carved into hundreds of slices for individual study, Haenecour said.

“So the short answer is that there is a lot we can do with very, very small particles,” he said. “For us, having 100 milligrams of something is decades worth of work. We can work on this forever.”

The quick-look team also includes Lindsay Keller from NASA’s Johnson Space Center; Tim McCoy, curator of meteorites for the Smithsonian; Ashley King from the Natural History Museum in London; and UA alum Michelle Thompson, now a professor at Purdue University in Indiana.

A handful of lab scientists and technicians at Johnson round out the team, Zega said.

Team members have been practicing their quick-look procedures since last year. They expect to receive their tiny bit of Bennu within two days of the capsule’s return to Earth.

Usually, scientific work is detailed, deliberate and “you take your time doing it,” Zega said, but the quick-look process feels more like “shift work.”

“We literally only have three days,” he said. “I’d be lying if I didn’t say that there is pressure involved in doing this kind of measurement, but the group that we’ve assembled is really good, very highly trained and capable scientists, and we’re all confident in our abilities to get the job done.”

The work will be done at the space center in Houston, where a new curation facility has been built specifically to handle the Bennu samples and the spacecraft hardware used to collect them.

The facility is managed by NASA’s Astromaterials Research and Exploration Science Division, which oversees the world’s most extensive collection of extraterrestrial materials, including moon rocks, solar wind particles, meteorites and comet samples.

Big plans

OSIRIS-REx is now speeding back to Earth with an estimated payload of about half a pound of pebbles and dust from the asteroid.

As the spacecraft swings past the planet, it will jettison its sample-return capsule to reenter the atmosphere and land by parachute somewhere in the Utah Test and Training Range, west of Salt Lake City, at just before 8 a.m. Tucson time on Sept. 24.

A recovery team will collect the capsule from the range and secure it for transport the following day on a military flight to Houston, where the sample canister will be opened for the first time.

Once its contents have been painstakingly processed and curated, one quarter of the material from Bennu will be turned over for study by members of the mission’s science team around the world, including a number of researchers at the UA.

The remaining three-quarters of the haul from NASA’s first asteroid sampling mission will be set aside by the space agency for additional research by other scientists now and in the future. At least some of that work will almost certainly happen in Tucson.

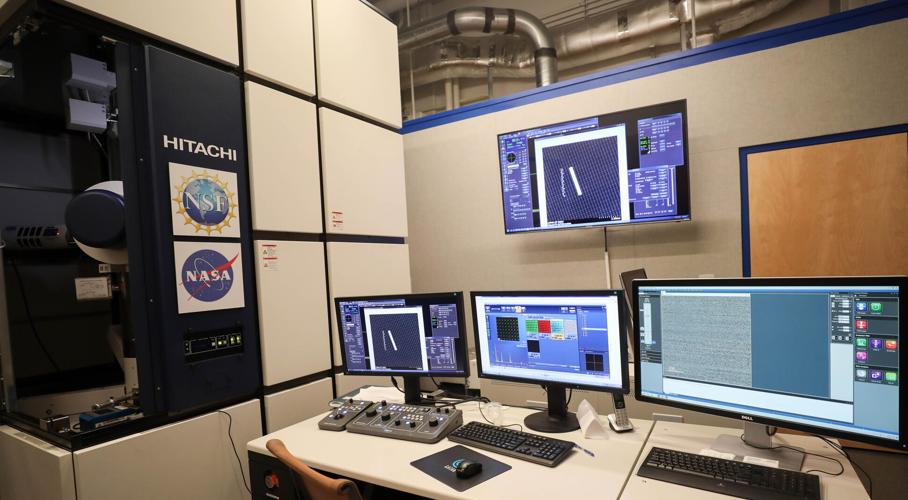

Zega also serves as director of the university’s Kuiper Materials Imaging and Characterization Facility, a collection of state-of-the-art labs he helped assemble over the past decade or so in the basement of the Kuiper Space Sciences Building.

On Wednesday, he led a media tour of the facility and its battery of electron microscopes, spectrographs and other advanced instruments, including one that uses an ion beam to cut those impossibly small slices from individual dust particles for further analysis.

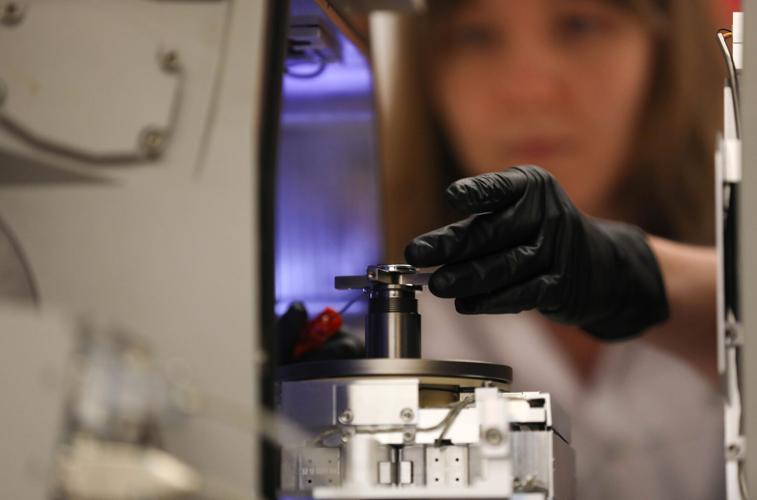

In one of the labs, a researcher was working with a lunar sample that was brought back during one of the Apollo missions, before she was born. The same sort of thing is expected to happen with the rocks and dust collected by OSIRIS-REx, which could fuel scientific work for generations to come.

“The kinds of instruments we have today, they didn’t have in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, and the kinds of instruments that we’re going to have 30 or 40 years into the future we don’t obviously have now,” Zega said. “Capabilities are always improving, and the kind of science that we can do in the future will be very different from the science that we can do today.”

NASA paid for the construction of the Kuiper Building in 1966, and in December, the space agency awarded the university a four-year, nearly $3 million grant to support OSIRIS-REx sample science and other work in the labs there.

Haenecour said the UA’s set-up at the Kuiper Building is on par with the new curation facility at Johnson Space Center.

“We’re basically one of the only universities in the U.S. with such a coordinated facility. We have all the instruments on site, so we can carry out all the measurements that we need to do with labs next to each other in the same building,” he said.

Tiny specks

Zoe Zeszut, manager of the lab in the Gerard P. Kuiper Space Sciences Building at the University of Arizona, opens the chamber to add a sample.

The “last piece of the puzzle,” as Zega described it, is scheduled for delivery to the UA on Thursday: a piece of scientific equipment called a NanoSIMS (short for nanoscale secondary ion mass spectrometry, of course).

Arriving just in time to analyze material from Bennu, the device can map the composition of elements and isotopes in a sample down about one-billionth of a meter.

Ultimately, scientists hope to learn about the origins of the solar system and life itself by examining clues preserved within the asteroid’s pristine, 4.5-billion-year-old rocks.

Zega already has big plans for the first sample he gets into his lab at the UA.

“I want to slice and dice it, and I want to look at it in this instrument here,” he said, motioning to the transmission electron microscope behind him. “We think because (Bennu) is a carbonaceous asteroid of a certain type, it’s probably full of organic compounds and minerals that formed through reaction with water. That’s among one of the first things I hope to see.”

Haenecour said he, too, will be scanning for “very, very small organics” in the asteroid samples, as well as microscopic grains of stardust that are measured in nanometers and predate the solar system. A lot of the stuff he is looking for is roughly the same size as an individual flu virus cell, he said.

The UA should get a head start on such research.

Once Haenecour and Zega wrap up their work with the quick-look team in Houston, the two scientists plan to return to Tucson with a few of the asteroid particles that were used for the initial characterization.

Those will be the first pieces of Bennu to be brought back for further study at the university where the OSIRIS-REx mission was born.

Haenecour said the priceless grains of dust will be sealed away in little airtight vials, so he will probably just stash them in his carry-on bag.

It should make for a memorable flight, he said. “That’s going to be very stressful and very exciting at the same time.”