On Thursday afternoon, 13 high schoolers gathered at the front of their science classroom for a polling exercise to gauge their beliefs when it comes to drugs and substance use.

Facilitator Monica Contreras read the statement, “Teens use more drugs than adults,” and the students filtered towards the center and right side of the room, indicating their partial or full agreement with the statement.

The lone participant on the “disagree” side was their principal, Kim Babeu, who came to Envision High School at the end of 2020 after spending years on the faculty of Toltecalli, a charter school on Tucson’s south side.

For the next statement — “People who use drugs are bad” — the entire group migrated over to Babeu’s side of the room, standing firmly in staunch disagreement with the sentiment.

The first several questions of the poll reflected a variable mix of agreement, disagreement or students who fell somewhere in the middle, but the statement about drug users being bad was the only question in the lot of 10 that generated 100% agreement among participants.

When Contreras read the next statement, “Drug addiction is a disease,” a lone student who had previously told his classmates about a family member’s struggle with addiction and mental health issues walked firmly across the room to the “agree” side, head held high as he turned to face the rest of the group. Babeu was already walking toward him, and most of the other students followed suit.

The poll came in the middle of a discussion about substance use, as part of Chicanos Por La Causa’s Nahui Ollin Wellness program, which is taught weekly at schools across Pima County.

Catering to the youth experience

The program aims to empower students with the tools to build a foundation of healthy behaviors, a sense of purpose and improved decision-making habits.

Nahui Ollin is strengths-based, meaning it emphasizes people’s positive traits and self-determination. The program explores culture, identity, character, relationships with family and peers, communication, health, community engagement, leadership and social justice.

The curriculum includes education about mental health, domestic and dating violence, healthy relationships, teen pregnancy and substance use.

Educators say it incorporates Indigenous ancestral knowledge to convey universal values — such as respect, confidence and pride — that exist across cultures.

The program has been taught in Pima County schools for the past 25 years, serving more than 600 students a year. The program is taught annually in Tucson and Sunnyside school districts, and Nahui Ollin was the driving force behind the creation of CPLC’s tuition-free charter high schools, including Tucson’s Toltecalli and Envision, said CPLC of Southern Arizona President Lydia Aranda.

The program recently came into the public eye when the Pima County Board of Supervisors voted to reallocate nearly $40,000 of funding intended for the Arizona Bowl to CPLC and Nahui Ollin. The decision was the result of inflammatory statements and tweets made by the founder of the bowl’s title sponsor, Barstool Sports’ Dave Portnoy.

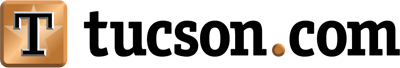

Classes are taught by Contreras and Jesus “Chucho” Ruiz, youth prevention and cultural specialists with CPLC. They travel across Pima County visiting participating schools to teach the curriculum, but schools also work independently to deliver the program in various classes and after-school groups.

Nahui Ollin focuses its lessons to underserved youths and youths of color, bringing in culturally responsive practices to connect with kids. The program, which has an emphasis toward LatinX, Chicano and Indigenous youths, was the vision of former CPLC Executive Vice President Lorraine Lee.

To make sure it was meeting the needs of its participants, CPLC partnered with a research and development firm in Phoenix to conduct surveys and draft reports based on the findings.

It also sought out grants to expand the program, and began working with larger school districts, before eventually starting its own community-based schools. Toltecalli opened in 2003, moving to its new location a few years later, and Envision was started in 2017. The schools and Nahui Ollin integrate social and emotional skills into the curriculum.

With guest speakers, educational workshops, wellness fairs at Envision and Toletecalli, a spring conference and an annual retreat, Nahui Ollin has expanded exponentially, Ruiz said.

“Part of what allows us to continue to do the work we do is our program is really centering the youth voice and youth experiences and learning from them,” Ruiz said. “Really facilitating a space about what wellness means from a holistic perspective. For us it’s not what are you going to be when you grow up, it’s how are you going to be?”

One of the main purposes, Ruiz said, is that often, adults aren’t really listening to young people. Nahui Ollin wellness program works hard to do the opposite.

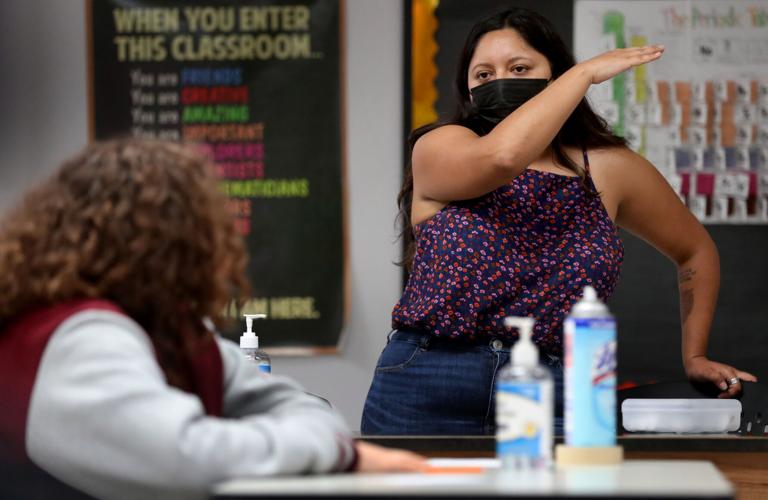

Monica Contreras with the Nahui Ollin Youth Wellness Program talks with high schoolers about substance abuse. "You deserve comprehensive drug education," she tells students. "There's so much left out when the conversation is 'Just say no.'"

Comprehensive drug education

During Thursday’s class, Ruiz thanked everyone who spoke up for sharing and those who didn’t speak for listening. He validated their statements and responded with phrases like, “What I heard you saying was ...”

After a few icebreaker questions at the start of the class, Contreras and Ruiz moved into the meat of the lesson, getting to the two focal questions of the day: What is a drug and what’s the first thing that comes to mind when you hear the word?

The students wrote their answers quietly on notecards before Ruiz asked if anyone wanted to share.

“It’s a type of medicine, but to me it’s also a thing that can ruin lives,” one student said, before talking about his own family’s experience with a loved one who needed medication for mental health issues but also used heroin. He talked about the impact to his mother’s life and his own, and what his family learned as a result.

“When people share, it’s a gift,” Ruiz said, before thanking the student.

Ruiz also reminded the class that consideration of other people’s situations and experiences is critically important. Things can look different when you take into account factors like race, socioeconomic status or disability, he said.

“The more aware, the more woke you are, the more you have an advantage in making healthy choices,” Ruiz told the group.

Contreras talked about the education she received growing up through drug-prevention programs like D.A.R.E., saying the tactics weren’t very effective.

“You deserve comprehensive drug education,” Contreras said. “You all are worthy and deserving of information more encompassing, real and genuine. There’s so much left out when the conversation is ‘Just say no.’”

‘We’re in this together’

Babeu, the Envision High School principal, said it’s important to not only talk the talk, but also walk the walk when working with kids and teens. She shared right along with the students during Thursday’s class, talking about her family’s and her own experiences.

Envision and other CPLC schools have taken the “walk the walk” mentality outside of Nahui Ollin, which addresses social justice in its curriculum.

CPLC’s schools have dismantled punitive measures of discipline and all staffers are trained in restorative justice, which emphasizes accountability and making amends rather than punishment.

Students participate in restorative circles, in which there is equal sharing and listening by a person harmed and the person who did harm. Students also help decide their own discipline, and, because there are no longer suspensions, do not miss out on opportunities to learn.

Ruiz teaches Nahui Ollin weekly at the CPLC schools as well as Sunnyside and Desert View high schools. In order to reach other schools that want to participate, Ruiz identifies faculty members to partner with and attends classes as a guest speaker on various topics.

With many community partners, the program also provides referrals and introduces students to local resources.

“I think one of the great things that describes the experience they create for young people is it’s about connecting and being intentional with yourself so each and every person can go forward and make better decisions,” Aranda said of her colleagues’ efforts.

It’s part of an approach called “La Cultura Cura,” which recognizes that a person’s, family’s or community’s cultural values play a huge role in their development and well-being.

Providing for the whole child

Nahui Ollin has made a difference for teachers and counselors in the Sunnyside Unified School District, said Elizabeth Allen, who leads the district’s Project AWARE program. AWARE, which stands for Advancing Wellness and Resiliency in Education, offers mental health support and education to Sunnyside students, families and staffers.

One of AWARE’s goals is to destigmatize mental health, which aligns with Nahui Ollin’s teachings. AWARE also aims to connect families with resources.

“For our high schoolers, one of the things we realized was making sure we had extra supports for them,” Allen said. “Typically high school students are the ones that take on more responsibility at home, especially if there’s a younger sibling.”

That’s where Nahui Ollin has come into play, and for years it’s been integrated into the curriculum in some classes, as well as offered in after-school and lunchtime groups for students.

Even with the recent focus on mental health as a result of the pandemic, there’s still destigmatization work to be done, especially within certain cultures. Mental health issues are still very stigmatized for Sunnyside’s Native American population and LGBTQ+ issues are difficult for Hispanic men to navigate in some households, Allen said.

Nahui Ollin functions primarily as a club at Desert View and Sunnyside highs, but it’s also taught in health, social studies and other classes on a weekly basis.

Allen said the district’s challenge is finding when to run the classes so they reach the most students, but they also have to evaluate how much regular curriculum will be given up in those classes as a result.

With district leaders and teachers prioritizing the support of students’ mental, social and emotional success alongside their academic success, Nahui Ollin provides the holistic approach Sunnyside was looking for as a way to help its high school students, Allen said.

“We need to be able to provide as much as possible for the whole child,” she said.