Drive down many of the streets in the Cherry Avenue neighborhood on Tucson’s south side, and rock and gravel are the most common sights you’ll see in yards.

A couple of trees dot many yards, but smaller shrubs, grass and even cacti are rare. Commonly, the scene is barren in the neighborhood bounded by Park Avenue and Tucson Boulevard on the west and east and Irvington and Drexel roads on the north and south.

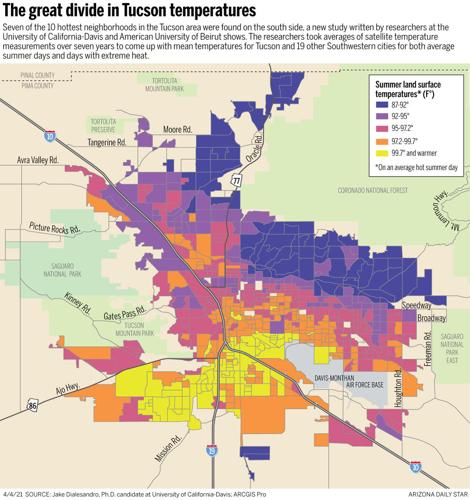

Such scenes, experts say, explain why a new study found most of Tucson’s hottest neighborhoods lie on the south side, stretching beyond city limits. There’s less shade from trees, and rock and gravel absorb heat, release it into the air and make the area hotter.

On an average summer day between 2013 and 2019, late-morning temperatures in the hottest south-side neighborhoods exceeded citywide averages by 7 to 8 degrees Fahrenheit, the study found. They topped temperatures in the Catalina Foothills and some northwest-side suburbs by up to 12 degrees Fahrenheit.

The Tucson findings were part of a regional study that used satellite-gathered data to compare temperatures in poorer and more Latino-based areas to those in wealthier and whiter ones. It covered Tucson and 19 other Southwestern cities, from Los Angeles, Sacramento and Palm Springs on the west and east to Houston and Dallas.

A lack of rain in late 2020 may mean a disappointing wildflower season. Let us fill in the gap with this compilation of wildflower videos from former Arizona Daily Star reporter Doug Kreutz.

In all cities studied, researchers found that on an average hot day, summertime temperatures were significantly hotter in poorer neighborhoods and those dominated by Latinos than those predominantly white and with higher incomes.

In the Tucson area, the study included 8,400 square miles. Researchers found River Road, which separates Tucson from the wealthier, higher elevation Catalina Foothills, “is almost like a curtain of heat,” said lead study author Jake Dialesandro, a Ph.D. candidate at the University of California-Davis.

“It seems like there is a barrier where the heat is divided — a dividing line,” Dialesandro said of River Road.

“The heat is not seeking out low-income neighborhoods or Latino individuals,” he said. “It just happens these areas have a lack of green space, basically just concrete barren desert.

“Let’s say you got to Casas Adobes or the Catalina Foothills, there’s a lot more vegetation present. That’s through irrigation.”

The city has a big exception: “Reid Park — there’s nothing but grass and trees,” Dialesandro said. “That’s a cool area.”

Income disparities

Geography also plays a big role in temperature disparities between south and north in the Tucson area. As the elevation climbs heading north, temperatures drop.

But the cooler areas also have much higher housing prices than the urban core — accentuating neighborhood temperature disparities.

“Residents of these areas with highest burden of heat have the least resources to mitigate the heat,” Dialesandro said.

“If you are a resident in the southern area of Tucson you need more electricity to cool your home to get comfortable temperatures. But you make the least amount of money.”

Often, such residents must choose between paying rent and paying utility bills to cool their home, but wealthier residents up north needn’t make that choice, he said.

Communities of color on “the front lines”

City of Tucson officials say they’re well aware of these disparities, although this study documents them in greater detail than past research.

They’re trying to help the city’s poorer neighborhoods, including those on the south side, with a program to promote “green infrastructure” using rainwater harvesting to grow vegetation. One reason is so people save money on water bills. The other is to conserve our drinking-water supplies.

Most notably, Mayor Regina Romero has pledged to get 1 million new trees planted by 2030. The effort will intensify this year, with particular attention to disadvantaged areas, after a slow start last year due in part to the COVID-19 pandemic, she said.

“Maybe two years ago or a little bit more, we started seeing the degrees of temperature within low-income communities in the urban core of Tucson were higher,” Romero said in an interview last week. “That’s why I think that with our world getting hotter, especially here in the Southwest, the front lines of that are communities of color, women, children and seniors, and those that work outside.”

Neighborhood leader documents differences

Beki Quintero of the south side’s Sunnyside Neighborhood says she can feel temperature differences when driving north.

“When I drive to Oro Valley and Marana, you can first see the dreary decay and then you can see the lush green grass and the beauty when you head further north,” said Quintero, a Tucson native, a 48-year Sunnyside resident and secretary-treasurer of the Sunnyside Neighborhood Association.

“When you go up there and see shade structures, trees and grass, you can feel the difference,” Quintero said.

She has documented temperature differences between barren and lush landscapes just in her neighborhood, at Fiesta Park near Alvord Street and Liberty Avenue.

Awhile back, she stuck a thermometer in the ground at the park’s Peace Garden, adorned with mesquite, lime, orange and Texas mountain laurel trees. It read 94 degrees.

She moved to a more barren area of the park. The thermometer registered 151 degrees, she said.

“You go to parks in other parts of town, they have structures for kids to play in and a lot of shade trees. Take Morris K. Udall Park” on the northeast side, Quintero said.

“They have a lot of trees and a splash pad. It’s green. It’s pretty,” she said. “At Mission Manor Park in Sunnyside, the trees are older. They’re dying, and they’re not being replaced.”

Heat island map

The new study used satellites that recorded temperatures on an “average hot day” on 48 days in each city. The temperature was recorded at 10:30 a.m. in Tucson, when the satellite consistently flew overhead, Dialesandro said.

To monitor extreme heat impacts, researchers compared temperatures on the warmest day they could find that was cloudless, when the satellite worked most effectively, he said.

They also compared temperatures across neighborhoods on an average summer night.

The study’s widest temperature disparities came in California, possibly because its affluent areas contain unusually lush vegetation, researchers concluded. The study was published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

Of the 20 cities, Tucson had the third biggest temperature disparity on average summer days. On extreme heat days and at night, the disparities in Tucson were among the lowest among cities.

The study’s research methods were sound and its conclusions appear valid, said Stephen Yool, a retired University of Arizona geography professor who has researched urban heat issues. With some caveats, the findings are statistically significant, said Yool.

While other studies have examined temperature disparities like these, including one in Phoenix, this is the first to look at them at a neighborhood scale, he said.

This study is “very important,” agreed Ladd Keith, assistant professor in the UA’s School of Architecture and Planning.

Its findings aren’t surprising, matching for Tucson what’s shown on a heat island map prepared last year by the regional Pima Association of Governments, said Keith, who worked on that map.

Rainwater harvesting: mixed success

To mitigate urban heat, the city has subsidized rainwater harvesting since 2012 by giving rebates up to $2,000 to homeowners to buy cisterns and other harvesting equipment. That was to encourage planting of trees and other vegetation without using potable water.

But by 2016, it was clear the vast majority of rebates went to wealthier families in the foothills and other unincorporated areas served by Tucson Water. So the city launched a loan program for poorer neighborhoods and a campaign to encourage them to seek rebates.

The most recent statistics, from fiscal year 2018-2019, show improvements.

The south side’s Ward 5, which finished last in rebates in 2016, had the third largest percentage by 2019 — but still small at 10%.

The biggest share of rebates, about 30%, was still going to unincorporated areas.

Small lots, less greenery

On a small scale, a south-side greening/water harvesting success story did occur at Star Academic High School in the Sunnyside School District. There, since 2018, volunteers from UA, the community and the high school have worked together to plant trees and dig basins to capture rainwater. The school principal himself was watering trees there on weekends.

Since then, the trees have grown and “they are a lot more mature,” said Adriana Zuniga-Teran, who co-authored a research paper on the harvesting project as an example of university-community engagement on “green infrastructure.”

But she and her research partner, UA professor Andrea Gerlak, found simultaneously that the city’s harvesting rebates weren’t reaching this community overall, Zuniga-Teran said.

“The big problem in these low-income areas is that you are exhausted from work” and don’t have time to maintain cisterns and other harvesting equipment, she said.

“Another piece of the puzzle is the density on the south side. In other parts of town, the lots are larger. If you have a small lot with a little yard, how much greenery can you put in?”

And if you’re renting, “you are really not interested in improving the property. The property owner is somewhere in California and they are not interested,” Zuniga-Teran said.

In the Cherry Avenue Neighborhood, Maureen Fisher, who co-chairs the area’s neighborhood association, said she dreads the summer heat and doesn’t go out much in the summer.

But she doesn’t see many people get water harvesting rebates and doesn’t expect much more harvesting in the future.

She installed a jury-rigged harvesting system at her home in 2014 for about $200, without getting rebates. She puts harvested rainwater on her oleander bushes, creosote bushes and desert willow and salt cedar trees.

“You’ve got to apply to Tucson Water and meet their specifications to get rebates, and you’ve gotta get it installed. I don’t know if people here have the money to do that,” Fisher said.

Plus, a lot of yards in the neighborhood are small, limiting their ability to accommodate many plants. Also, 70% of the residences in the area are rentals, again limiting people’s interest in long-term planting efforts, she said.

ambitious goal: a million trees

The mayor’s tree planting campaign will go beyond rebates.

The city has been collecting for many months now a “green infrastructure fee” on residents’ water bills to pay for more tree plantings and water harvesting efforts. It is starting a “mini-grant” program offering grants totaling $40,000 apiece in each city ward to pay for green infrastructure projects on a neighborhood scale.

Romero has hired an urban forestry manager and an environmental-sustainability adviser to guide tree planting.

Also, the city hopes to secure money from private companies to shoulder some tree planting costs, she said. Acknowledging the tree planting is behind schedule due to the pandemic, Romero said that down period gave the city time to ramp up the program and hire people to manage it.

Since officially launching the tree program a year ago, the city has planted 13,945 desert-adapted shade trees in 30 neighborhoods by itself and with groups such as the nonprofit Trees for Tucson.

Of those neighborhoods, 24 are considered “heat vulnerable,” based on the number of young children, elderly people and households with incomes below poverty level, said Fatima Luna, Romero’s sustainability adviser.

The city has obtained a grant from Coca-Cola for a major tree planting program in the Barrio Centro neighborhood, lying south of 22nd Street and bounded by Tucson Boulevard on the west and Country Club Road on the east. Before Christmas, “we will plant a grove of trees there” to serve as a cooling center, said Katie Gannon, director of Trees for Tucson.

The city is also working on a comprehensive plan for the tree-planting, including annual goals and identifying potential “community partnerships” to support the 2030 goal, Luna said.

“We have to plant 100,000 trees per year” to reach the 2030 goal, Romero said. “It’s an ambitious goal, but we’ve got to set those ambitious goals to be able to try and hit the target.”

“We’re trying to cool the Tucson valley”

In the Sunnyside Neighborhood, Trees for Tucson planted 200 trees from November through March in the homes of residents who wanted them. They included sweet acacia, palo verde, mesquite and red push pistache trees.

“They were just 5-gallon trees, but we will see a difference in five years,” neighborhood leader Quintero said. “‘Patience is a virtue’ is my motto.”

And over in the Cherry Avenue Neighborhood, the Tucson Parks and Recreation Department pledges to plant a lot more trees at an existing park and recreation center on the avenue just south of Irvington Road. The $765,000 to cover that and other upgrades at the park comes from the $225 million bond issue that city voters approved in November 2018.

At the same park, the Pima County Regional Flood Control District plans to dig three new water harvesting basins, to capture rainfall runoff and grow more trees and shrubs.

While a neighborhood survey of about 30 residents didn’t put more trees “super-high” on the priority list, “tree planting is a high priority for the city, the mayor and the council,” said Tom Fisher, a City Parks and Recreation Department project manager.

“We’re trying to cool the Tucson valley,” Fisher told a virtual meeting with neighborhood residents last Tuesday. “With all the asphalt, all the building, the more trees we can put out there, the greener it will be, the cooler it will be.”