Even though Tucson gets most of its water from the Colorado River, its top water official says the city can withstand the deepest cut it’s likely to get from that supply in the foreseeable future.

This assurance comes after researchers recently warned the Colorado River Basin could face severe future cuts in water supplies due to climate change and other pressures.

The “worst plausible scenario” of a cut the city could face is 50% of its total Colorado River allocation from the Central Arizona Project canal system, said former Tucson Water Director Tim Thomure. He still oversees the utility as interim assistant city manager.

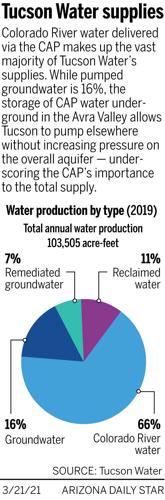

Much of the water that could be cut is currently not used to serve customers, he said. The city stores more than one-third of its CAP supply in large basins for future use. From there, the water sinks into the ground to replenish, or recharge, the aquifer.

While Tucson may have to pump more groundwater in the future because of CAP cuts, Thomure said the aquifer typically has been naturally replenished by enough rainfall and runoff to compensate for the most likely worst-case shortfalls in CAP deliveries.

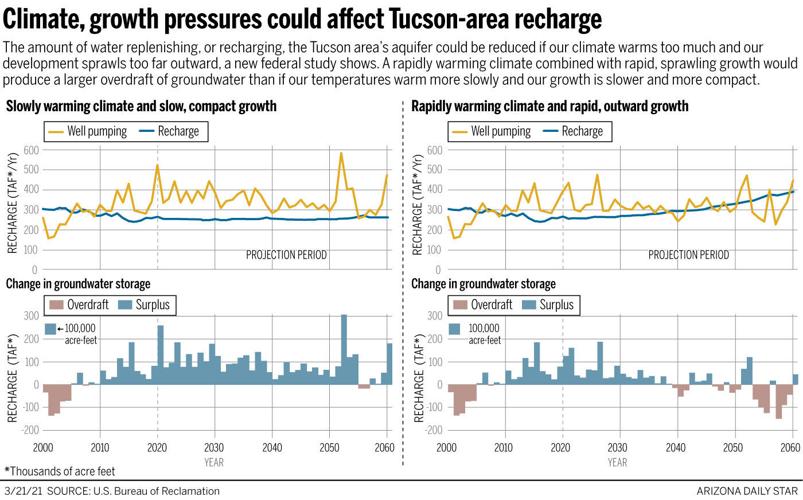

But a big unknown clouding Tucson’s future water picture is how climate change might interfere with natural recharge of the aquifer by reducing rainfall and increasing evaporation.

A new federal study warns that continued heating of the planet could reduce natural recharge, noted Kathy Jacobs, a top University of Arizona climate scientist.

That calls into question the city’s estimates of how much recharge we’ll get in the future. Jacobs’ point is "well taken,” Thomure said.

“Resilient position” even with a 50% cut

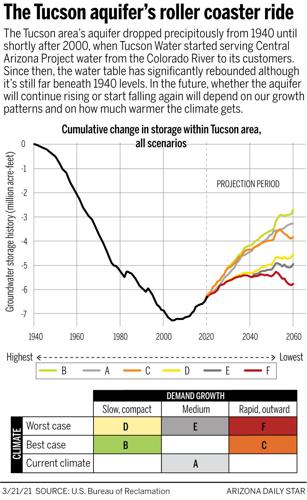

The longstanding concern about possible cuts to the CAP is that a return to heavy pumping would reverse a trend of significantly rising aquifer levels under the city since the CAP went online here in 2001.

Since that year, Tucson Water’s groundwater pumping has decreased dramatically.

Tucson’s annual CAP allocation is 144,191 acre-feet — enough to serve about 575,000 households for a year.

However, the biggest share of CAP water that the city would lose is now being used to recharge the aquifer through the basins in Avra Valley west of Tucson and on Pima Mine Road south of Tucson.

That’s why a 50% reduction in CAP wouldn’t require enough groundwater pumping to cause significant problems with the aquifer, such as subsidence, Thomure said. Subsidence is the collapse of the ground surface as water is withdrawn from underneath.

The Central Arizona Project is a 336-mile canal in Arizona that supplies Colorado River water for the Phoenix and Tucson area, agriculture and several Native-American tribes. Construction began in 1973 and was substantially complete by 1994. This portion is located near Sandario Road and Mile Wide Road west of Tucson on March 17, 2021. Video by: Mamta Popat / Arizona Daily Star

The natural replenishment of the aquifer in Tucson Water’s service area would compensate for the pumping the utility would do, Thomure said. “We can be in a really, still resilient position with up to a 50% cut,” he said.

“The worst case scenario is that we’re pumping 25,000 acre feet a year,” half the water that naturally recharges the aquifer in the service area, Thomure said.

Jacobs, a former Tucson office director for the Arizona Department of Water Resources, said she agrees with Thomure’s forecast of how much CAP water the city would lose in the worst case.

She also agrees with other experts who say Tucson Water has done a good job in managing its water resources, in part by recharging much of its CAP supply.

Tucson Water has access to a significant amount of groundwater today, due to its extensive wellfields inside the city and landholdings and wellfields in the Avra Valley, she said.

In fact, Tucson has access to the “largest allocation of groundwater for any utility in the state,” and the largest CAP water allocation of any Arizona utility, she said.

Together, the CAP and groundwater allow Tucson Water to be designated as having an assured, 100-year water supply — a state requirement for it to serve new development.

Federal study shows potential pitfalls

But the new study done by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation concluded there’s likely to be less water in our aquifer if Tucson-area temperatures rise fast enough and development spreads out far enough.

That calls into question whether the numbers Tucson Water uses for natural recharge will be borne out by future climate conditions, said Jacobs, who is director of the UA’s Center for Climate Change Adaptation, Science and Solutions.

Responding to Jacobs, Thomure agreed future projections indicate the region’s climate will get hotter and possibly drier.

But it’s “notoriously difficult” to predict how climate change will affect Southern Arizona’s monsoon, he said, and it’s a major source of rainfall and recharge here.

“Regardless, the conservative assumption is that future natural recharge rates may decrease, or at least become more variable,” he said. “Therefore, our working assumption of 50,000 acre-feet per year of natural groundwater recharge in our supply wellfields could indeed decrease over time.”

Uncertainty about recharge isn’t an immediate crisis — it’s a long-term issue, Jacobs said.

If the water table does start falling again, subsidence could occur and pumping must be planned to minimize it, she said.

“They may need to be more creative in the way they manage their wellfields,” she said . “If your objective is minimizing subsidence, you want to properly manage your withdrawals in areas of subsidence risk.”

“The issue is that when you are in a developed area with a lot of infrastructure, subsidence of any magnitude can cause damage,” Jacobs said. “Even small changes in the land surface can break water and sewer pipelines, roadways and flood control structures.”

River entering uncharted territory

Thomure’s comments come as the river enters a new era of unknowns, led by warnings coming from a recent study by Utah State University about the Colorado River Basin.

That study warned that if river flows drop 6.5% for every 1.8 degree Fahrenheit temperature increase, as some researchers project, “aggressive commitments to water conservation” will be needed in the Lower and Upper Colorado River Basin states.

Such conservation would provide a minimal level of water storage security in the region’s two big reservoirs, Lake Powell and Lake Mead, the study said.

For the three Lower Basin states, including Arizona, cutbacks of up to 40% of their Colorado River supplies may be necessary to keep reservoirs from falling too low, it said.

That dire conclusion assumes the river’s flows keep declining as they’ve done since 2000, due in part to climate change.

If river flows maintain their current, reduced levels, cutbacks will still be needed, but they wouldn’t be as severe as if the flows keep dropping, the study said.

Politically, the river is also entering uncharted territory. The seven river basin states including Arizona are preparing to renegotiate guidelines for managing the system’s reservoirs that expire in 2026, 19 years after they were approved.

The states also agreed in 2019 to a separate drought contingency plan to try to stabilize water levels at Lakes Mead and Powell by agreeing to reduce their take from the river as the lakes fall below certain levels. That pact also expires in 2026 and will have to be revisited and most likely revised.

Thomure called the Utah State study “well done.” It achieves its stated goal, “to put out some provocative ideas and with the express intent of having people think more broadly and more creatively as we go into next negotiations on the river,” he said.

“They make a lot of assumptions and some of their conclusions are drawn from stacking worst-case scenarios on top of each other. That’s not a flaw, but it’s something that needs to be understood,” Thomure said.

“It’s not an unreasonable study but it’s also not making any specific prediction about the future. It’s providing a range of possible outcomes.”

How the worst case would play out

For now, Tucson stands to skate through the cuts approved in the 2019 drought plan.

At most, it would lose only 11% of its total CAP supply under that plan, and only when Lake Mead drops to or below 1,025 feet, about 60 feet lower than today’s level.

But negotiations over revising the 2007 guidelines and the 2019 drought plan could lead to agreements for larger cuts if the river’s future stays gloomy.

Thomure’s view of the worst-case scenario for Tucson is based on the possibility of the entire CAP — which also serves Phoenix, farms and tribes — losing 67% of its total supply in the future.

That’s more than the 2019 drought plan envisions. That plan would cut CAP at most by nearly half its total supply — 720,000 acre-feet — after seven years if Lake Mead dropped low enough.

If CAP were cut 67%, municipal and tribal CAP users would probably lose about 472,000 acre-feet total, Thomure said. That’s enough to serve more than 1.5 million households for a year.

Based on Tucson’s proportional share of the entire CAP supply, the city would lose about 47% of its allocation, said Thomure.

He chose to up the worst-case cut to 50% to simplify calculations for planning purposes.

With a 50% cut, Tucson would have a little less than 75,000 acre-feet of CAP left.

But since the utility uses around 110,000 acre-feet annually — its total 2019 deliveries were 103,000 — and it gets another 10,000 acre-feet annually in reclaimed water, that means it would face a gap of no more than 25,000 acre-feet to be made up by pumping, Thomure said.

He said natural recharge will allow the utility to “physically and sustainably pump twice this much groundwater indefinitely.”

The 50,000 acre-feet recharge level was first mentioned in a 2004 city of Tucson 100-year water plan. “For planning purposes, it is conservatively estimated that Tucson Water can withdraw 50,000 acre-feet of ground water each year without causing significant water-level declines within its projected service area,” the plan said. That calculation was supported by a groundwater model created and used by the Arizona Department of Water Resources, Thomure said.

An Even deeper cut is called survivable

Even a 75% cut in CAP deliveries could be handled without substantial pumping increases, Thomure said.

Tucson Water then would have a little more than 40,000 acre-feet left, or only enough to serve 160,000 households for a year. It would have to pump around 60,000 acre-feet, more than its available natural recharge.

But to compensate for that, Tucson Water would be able to tap into treated sewage effluent it has started recharging into the aquifer for its Santa Cruz River Heritage Project, begun in 2019, and its Southeast Houghton Area Recharge Project, started last year.

These calculations will be updated for a new “One Water 2100” city plan, scheduled for completion in 18 to 24 months, Thomure said.

That plan will also contain a detailed assessment of the risks to the city’s water supply from climate change — the first such detailed analysis the utility has done, he said.

Beyond the natural recharge it gets annually, the city legally has the rights to pump a total of 3.3 million acre-feet of naturally replenished groundwater already in the aquifer.

That’s enough to serve the city’s customers for more than 200 years, Tucson Water says.

However, Thomure said the utility doesn’t want to pump that much groundwater because of the risks of subsidence and poorer water quality as the aquifer declines.

The city also has the rights to pump more than 800,000 additional acre-feet of recharged CAP water that Tucson Water and the Arizona Water Banking Authority have placed in the ground here.

While Thomure said a 75% cut in CAP is not a plausible scenario, if it did happen, the city could still manage its water supply sustainably and indefinitely, he said.

“This scenario is ‘beyond worst case,’ yet the community is still OK,” he said.

But the city is revisiting its assumption of recharge availability as it prepares its One Water 2100 plan, Thomure added. It continuously monitors and adjusts groundwater operations in response to a variety of factors including water levels and water quality.

“That is why our robust and continued investment in our groundwater infrastructure is critical, even though groundwater is no longer our primary supply source,” Thomure said.

Photos: Water fills the desert at these spots around Tucson

Lakeside Park, Tucson

Updated

A father fishes with his two sons at Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, 8201 E. Stella Rd., in Tucson, Ariz. on Nov. 17, 2020. Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, an urban lake on the southeast side of town, is a popular spot for walking and fishing. The lake is stocked with catfish, trout, bass and sunfish.

Lakeside Park, Tucson

Updated

A duck runs on water at Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, 8201 E. Stella Rd., in Tucson, Ariz. on Nov. 17, 2020. Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, an urban lake on the southeast side of town, is a popular spot for walking and fishing.

Lakeside Park, Tucson

Updated

While fishing with family members, Jose Saenz places a caught rainbow trout in a basket at Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, 8201 E. Stella Rd., in Tucson, Ariz. on Nov. 17, 2020. Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, an urban lake on the southeast side of town, is a popular spot for walking and fishing. The lake is stocked with catfish, trout, bass and sunfish.

Lakeside Park, Tucson

Updated

A fisherman waits for a fish to bite their lure at Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, 8201 E. Stella Rd., in Tucson, Ariz. on Nov. 17, 2020. Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, an urban lake on the southeast side of town, is a popular spot for walking and fishing.

Lakeside Park, Tucson

Updated

The reflection of Chuck Ford Lake shows in avid fisherman Richard Espinoza's sunglasses while Espinoza fishes for trout at Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, 8201 E. Stella Rd., in Tucson, Ariz. on Nov. 17, 2020. Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, an urban lake on the southeast side of town, is a popular spot for walking and fishing. The lake is stocked with catfish, trout, bass and sunfish.

Lakeside Park, Tucson

Updated

A person walks around the lake at Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, 8201 E. Stella Rd., in Tucson, Ariz. on Nov. 17, 2020. Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, an urban lake on the southeast side of town, is a popular spot for walking and fishing.

Lakeside Park, Tucson

Updated

While fishing with her family, Aziza Ramirez waits for a fish to bite her lure at Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, 8201 E. Stella Rd., in Tucson, Ariz. on Nov. 17, 2020. Chuck Ford Lakeside Park, an urban lake on the southeast side of town, is a popular spot for walking and fishing.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

Several resident ducks ply the waters of the main pond as sun sets at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020. The park is one of the most popular bird watching sites in the county.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

Park goers stop for photos of a pack of javalina roaming the park just before sunset at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

A pack of javalina rush for the trees after getting spooked while nosing around the lawn for food at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

The sun goes down and the bats come out over the main pond at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

The island in the main pond has been renovated and the bridge completely replaced at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

A park patron and his dog stroll along the paths on the shores of the main pond at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

Some of the wetland vegetation is beginning to reassert a hold after months of work to restore and renovate the main pond at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

Bernie Kanavage and Toby take a break from their evening walk on the bank of the main pond at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020. The main pond was recently restored, a major renovation that shut the park down for months in late 2019.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

A pair of park goers get close-ups from an obliging duck along the shores of the main pond at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020.

Agua Caliente Park, Tucson

Updated

Sun set over the main pond at Agua Caliente Park, Tucson, Ariz., November 17, 2020.

Santa Cruz River, Tucson

Updated

Water flows in the Santa Cruz River south of downtown Tucson, Ariz. on November 16, 2020. The addition of reclaimed water to the Santa Cruz River has hastened the return of wildlife.

Santa Cruz River, Tucson

Updated

A cyclist rides along The Loop as water flows in the Santa Cruz River near the Crossroads at Silverbell District Park, in Marana, Ariz. on November 18, 2020.

Santa Cruz River, Tucson

Updated

A heron sits by the water in the Santa Cruz River near the Crossroads at Silverbell District Park, in Marana, Ariz. on November 18, 2020.

Santa Cruz River, Tucson

Updated

Water flows in the Santa Cruz River south of downtown Tucson, Ariz. on November 16, 2020.

Santa Cruz River, Tucson

Updated

Water flows in the Santa Cruz River near the Crossroads at Silverbell District Park, in Marana, Ariz. on November 18, 2020.

Santa Cruz River, Tucson

Updated

Water flows in the Santa Cruz River south of downtown Tucson, Ariz. on November 16, 2020.

Santa Cruz River, Tucson

Updated

A Vermillion flycatcher rests on a branch along the Santa Cruz River south of downtown Tucson, Ariz. on November 16, 2020.

Santa Cruz River, Tucson

Updated

A bird rests on a branch of a tree along the Santa Cruz River near the Crossroads at Silverbell District Park, in Marana, Ariz. on November 18, 2020.

Santa Cruz River, Tucson

Updated

Water flows in the Santa Cruz River near the Crossroads at Silverbell District Park, in Marana, Ariz. on November 18, 2020.

Sweetwater Wetlands, Tucson

Updated

Water flows near the entrance at the Sweetwater Wetlands, 2511 W. Sweetwater Drive, in Tucson, Ariz. on November 17, 2020.

Sweetwater Wetlands, Tucson

Updated

Ducks swim in one of the bodies of water at the Sweetwater Wetlands, 2511 W. Sweetwater Drive, in Tucson, Ariz. on November 17, 2020.

Sweetwater Wetlands, Tucson

Updated

Libby Sullivan, left, and Sue Bridgemon walk along one of the trails at the Sweetwater Wetlands, 2511 W. Sweetwater Drive, in Tucson, Ariz. on November 17, 2020.

Sweetwater Wetlands, Tucson

Updated

Libby Sullivan, left, and Sue Bridgemon do some birdwatching at the Sweetwater Wetlands, 2511 W. Sweetwater Drive, in Tucson, Ariz. on November 17, 2020.

Sweetwater Wetlands, Tucson

Updated

A duck flight at Sweetwater Wetlands, 2511 W. Sweetwater Drive, in Tucson, Ariz. on November 17, 2020.

Sweetwater Wetlands, Tucson

Updated

Cattails grow near a body of water at the Sweetwater Wetlands, 2511 W. Sweetwater Drive, in Tucson, Ariz. on November 17, 2020.

Sweetwater Wetlands, Tucson

Updated

Ren Sullivan watches a group of ducks at the Sweetwater Wetlands, 2511 W. Sweetwater Drive, in Tucson, Ariz. on November 17, 2020.

Sweetwater Wetlands, Tucson

Updated

Sunlight breaks through the trees at the Sweetwater Wetlands, 2511 W. Sweetwater Drive, in Tucson, Ariz. on November 17, 2020.

Reid Park, Tucson

Updated

James DeDitius points at ducks as he sits with caregiver Mary Figueroa on a bench next to a lake at Reid Park, on March 17, 2020.

Reid Park, Tucson

Updated

The city's new 4.5 million gallon lake and storage basin at Randolph (now Reid) Park, Tucson, in December, 1959.

Silverbell Lake, Tucson

Updated

The Arizona Game and Fish Department brought in 14,300 pounds of catfish from Arkansas to restock 21 lakes in the Core Community Fishing Program in Tucson and Phoenix. These catfish were dumped into Silverbell Lake on April 03, 2015.

Silverbell Lake, Tucson

Updated

Jim Skay fishes at Silverbell Lake, on March 13, 2020.

Silverbell Lake, Tucson

Updated

In this 2016 photo, Nathaniel Ortega, left, grins while his grandfather Michael Ortega helps remove a fish from his line during a fishing clinic at Silverbell Lake, located in Christopher Columbus Park at 4600 N. Silverbell Rd. in Tucson, Ariz. Nathaniel's catch was the first catfish of the day.

Sahuarita Lake

Updated

A person walks along Sahuarita Lake on March 5, 2020.

Sahuarita Lake

Updated

Ted Moreno reels in a line while fishing at Lake Sahuarita, on March 5, 2020. Moreno, who lives in Tucson generally goes between Lake Sahuarita and Kennedy Lake to fish for trout during the fall and winter months.

Sahuarita Lake

Updated

Sahuarita Lake in the town of Sahuarita south of Tucson is popular with anglers, walkers, cyclists and others and its waters range from dazzling blue to aquamarine depending on the light.

Sahuarita Lake

Updated

In this 2001 photo, Dan Hampshire works on the top designs of a 34-foot monument tower at the entrance to Rancho Sahuarita, an 8,000 home project on 2,500 acres that includes a yet-to-be-filled 10-acre lake (in background).

Sahuarita Lake

Updated

In this 2013 photo, a couple walk around Sahuarita Lake Park, 15466 S. Rancho Sahuarita Blvd.