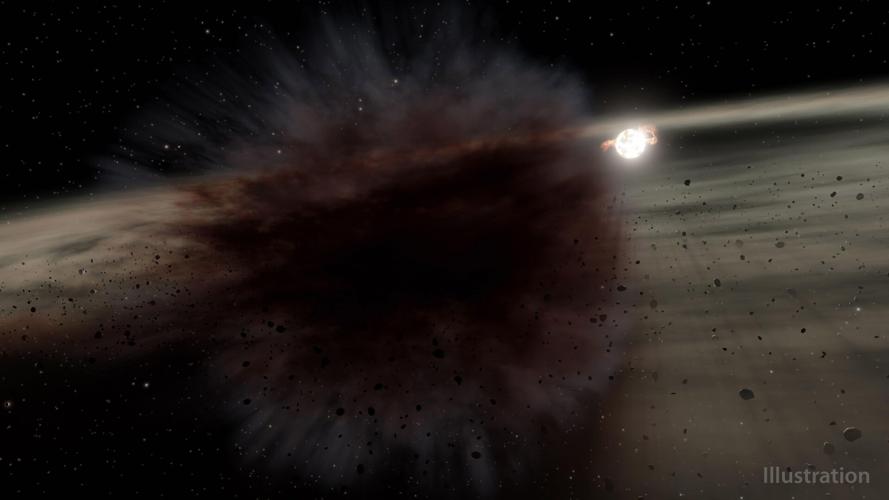

Astronomers from the University of Arizona have spotted the telltale signs of a massive crash between planet-sized objects orbiting a nearby star.

Their discovery marks the first time the debris cloud from such a collision has been observed — and measured — as it passed in front of its young host star.

The team led by Kate Su, a research professor in the UA Steward Observatory, used NASA’s now-retired Spitzer Space Telescope to collect more than 100 infrared images of the star, called HD 166191, between 2015 and 2019.

They chose the youthful star — just 10 million years old compared to our own 4.6 billion-year-old sun — in hopes of observing the early stages of planetary formation, when gas and dust collects and collides and eventually coalesces into planets and other rocky bodies.

“This star is very young. It’s like an infant, really,” Su said. “By looking at dusty debris disks around young stars, we can essentially look back in time and see the processes that may have shaped our own solar system.”

The astronomers noticed an abrupt change in HD 166191 in mid-2018.

In infrared images collected by Spitzer, the system 330 light-years from Earth grew suddenly brighter, suggesting an increase in dust and debris best detected in longer infrared wavelengths just beyond what human eyes can see.

The space telescope also captured signs of a debris cloud blocking the star, an observation confirmed by a ground-based survey telescope that saw HD 166191 dim slightly as the massive cloud of dust passed in front of it.

“For the first time, we captured both the infrared glow of the dust and the haziness that dust introduces when the cloud passes in front of the star,” said Everett Schlawin, assistant research professor at Steward Observatory.

“There is no substitute for being an eyewitness to an event,” added George Rieke, a Regents professor of astronomy at UA. “All the (previous) cases reported to date from Spitzer have been unresolved, with only theoretical hypotheses about what the actual event and debris cloud might have looked like.”

Su joked that she can’t pinpoint the hour or the day, but the evidence points to a massive smashup of planetary bodies sometime in early 2018.

Later observations by Spitzer show the resulting, star-sized dust cloud almost doubling in size through 2019 and into January of 2020, when NASA shut down the aging telescope for good.

“Our last observation is the day before they turned Spitzer off,” Su said. “It’s very sad.”

The astronomers used the data they collected before and after the collision to estimate the size of the cloud shortly after impact, the size of the objects involved and the speed at which the cloud dispersed.

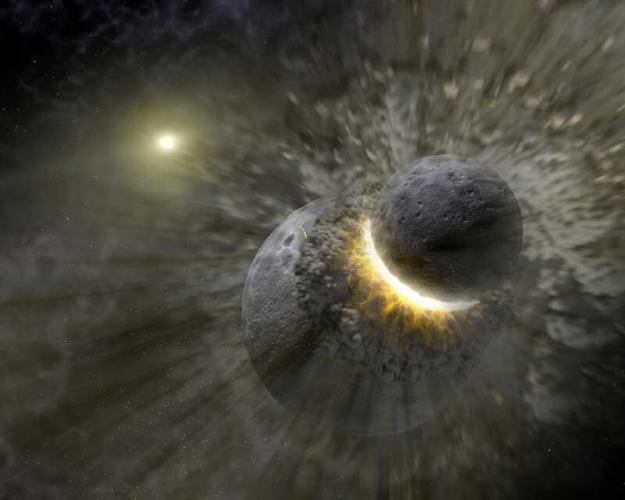

The main objects that crashed into each other were at least the size of Vesta, a rock 330 miles wide in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. And that’s at a minimum, Su said. “In reality they had to be bigger.”

The impact created enough heat and energy to vaporize some material, while setting off a chain reaction of other collisions in and around the resulting debris field.

Astronomer Phil Plait wasn’t involved in the discovery, but he described it in his popular science blog “Bad Astronomy.”

“Hundreds of light-years away two planetary objects slammed into each other at a speed likely to be tens of thousands of kilometers per hour, and the resulting catastrophic explosion of material expelled 100 quadrillion tons of dust. At least,” Plait wrote. “Whole planets colliding. I still have to remind myself that things like that are real.”

Similar cataclysms are thought to have led to the formation of the Earth and moon and other objects in our solar system.

Su and company published their findings on March 10 in the Astrophysical Journal. Co-authors on the study are Schlawin, Rieke, Grant Kennedy from the University of Warwick and Alan Jackson from Arizona State University.

As far as Su is concerned, their discovery could not have happened without the sort of “time-series observation” made possible by the unexpected endurance of the Spitzer Space Telescope.

She said she was hired at the UA 20 years ago to support the Spitzer mission, which launched in 2003 and was expected to last no more than five years. The telescope’s extra dozen years of life allowed her and fellow astronomers to target HD 166191 and routinely return to it to notice any changes.

Su hopes to check in on the young star and its disk of planet-making debris at least a few more times using NASA’s newest gadget, the James Webb Space Telescope, which launched on Christmas Day and is now having its powerful mirror aligned by scientists back on Earth.

As luck would have it, Rieke and his wife, UA Regents astronomy professor Marcia Rieke, helped design Webb’s two main infrared cameras. As a result, UA researchers have been allotted 13% of the new space telescope’s total observing time, the most of any astronomy center in the world.

A test image from NASA's Webb Space Telescope shows a spiky star, but the real stars of the show were thousands of ancient galaxies photo-bombing in the background. NASA's photo release isn't about what in the picture, but just that the new $10 billion telescope is working perfectly, even better than officials expected. This photo is a test image to make sure the system is working and it is. Scientists say 18 different hexagonal mirrors had to fit just right in place. And they did. And all this is happening 1 million miles away from Earth.