If Chicago had mild winters and mountains topped with telescopes, the Planetary Science Institute might not exist today.

The Tucson-based organization was founded in 1972 by a small group of scientists who split off from the Illinois Institute of Technology Research Institute to start their own firm.

Most of them had studied at the University of Arizona, so they knew this was the perfect place for what they had in mind — and not just because the sun shines more than 350 days a year.

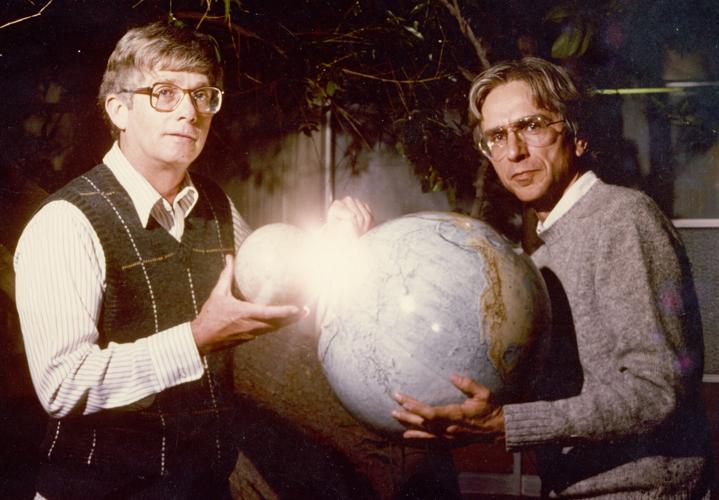

“As graduate students, we all had this thought that it would be neat to have an institute in Tucson that we could work at after we graduated,” recalled founder Bill Hartmann, now a senior scientist emeritus at PSI. “There are observatories on all sides of us and all these great (science) libraries. This is a great space city, a great place for astronomical research.”

The Planetary Science Institute will celebrate its 50th anniversary on Feb. 2 as one of the largest firms of its kind in the world.

That original team of four enterprising young researchers has grown to include some 115 scientists and 48 other employees, who manage hundreds of contracts with government agencies, universities and private sector firms in the U.S. and around the world.

The institute reported more than $15 million in revenue during fiscal year 2021. Roughly 95% of that funding came from NASA.

“Today, we are involved in basically all of the NASA solar system exploration missions, in addition to missions by other countries like Japan and (the European Space Agency),” said PSI director and CEO Mark Sykes, an accomplished planetary scientist in his own right.

“Likewise, the scientists who have joined us over the years have added to our depth of experience in almost every past NASA planetary mission, as well as more foreign missions, including China.”

The employee directory on the institute’s website includes asterisks next to the staff members who have asteroids named in their honor by the International Astronomical Union. There are now more than 40 asterisks in the directory, including ones for Sykes, Hartmann and fellow PSI founder and senior scientist Don Davis.

“We always wanted to be a fairly small, pretty tight-knit group of planetary scientists with overlapping interests,” Davis said. “That collaboration has been very fruitful for many, many, many years.”

And while they have failed spectacularly at keeping themselves small, Davis said they have always managed to keep science at the center of everything they do.

Ready for launch

PSI isn’t the only thing the Old Pueblo swiped from the Windy City.

In 1960, the UA lured pioneering astronomer Gerard Kuiper away from the University of Chicago to launch what would become the world famous Lunar and Planetary Laboratory.

Davis said bringing in Kuiper was “a great coup” for the UA and, eventually, PSI.

Two of Kuiper’s former students, Hartmann and Alan Binder, wound up working at the Illinois Institute of Technology’s research office in Tucson, before leaving to form their own local firm.

“It’s funny, because when I graduated (from the UA) with my Ph.D. in ‘66, there was no Planetary Science Department yet,” Hartmann said. “That hadn’t been invented, so my degree was in astronomy, and (Don’s) was in physics.”

After Davis graduated, he landed a job with a government contractor at NASA’s Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston during the Apollo program.

His team developed the computer codes used to guide the astronauts back from the moon, including some emergency return-flight contingency plans that helped save the crew of Apollo 13.

For their efforts, Davis and the rest of the Mission Operations Team were awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1970.

Shortly after that, he, too, went to work in the Tucson office of the Illinois-based institute where PSI was born.

It was an exciting time for the budding field of planetary science.

“The kinds of contracts we were getting were advising NASA on things, because they were desperate for information on space research,” Hartmann said.

“We were doing advanced mission planning for programs to follow on Apollo,” Davis added. “Boy, the world, the universe, the solar system was our baby at that time. We were going wild and having a great time doing it.”

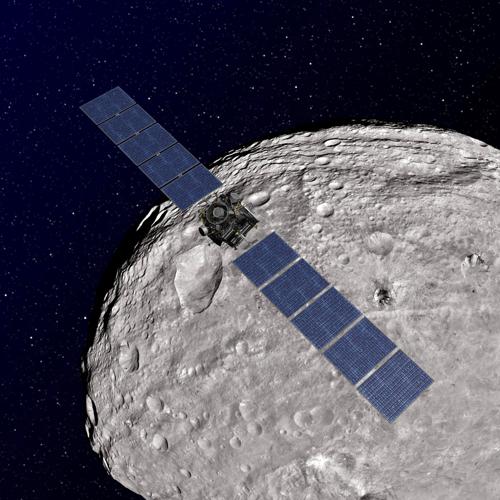

An artist's conception of NASA's Dawn spacecraft orbiting the giant asteroid Vesta. Tucson's Planetary Science Institute has a number of scientists working on the Dawn mission.

Early days

Once they decided to strike out on their own, they had to do so gradually. For legal reasons, they couldn’t all leave the Illinois institute at once.

Hartmann was the first one out.

For the first few weeks, the office number for their new venture rang in Hartmann’s living room. His wife, Gayle, had to rush to answer it before it woke their young daughter, Amy, from her afternoon nap.

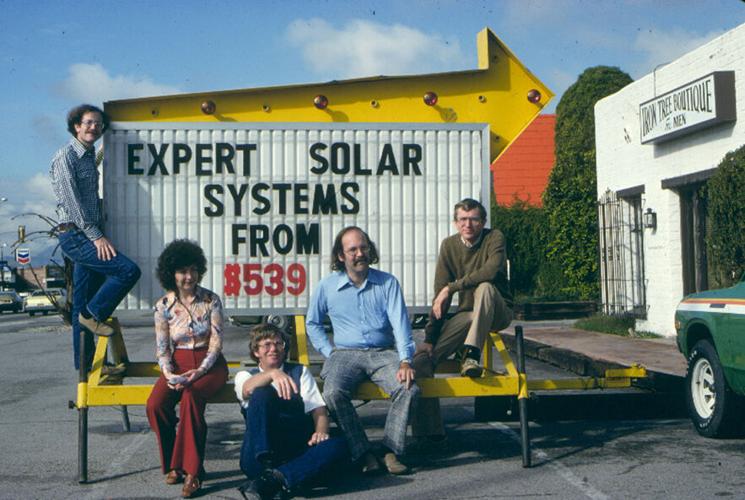

To help them get started, the Planetary Science Institute teamed up with what Davis described as a “small, dynamic new company” out of California called Scientific Applications International, better known today as giant government contractor SAIC.

The partnership provided them with the bridge funding they needed to get PSI off the ground, but there was one major downside: SAI was a for-profit corporation heavily involved in Defense Department activities.

“People who did not know us would castigate us as being ‘Planets for Profit,’” Davis said.

One of PSI’s first contracts was one Hartmann brought over with him from the Illinois institute: processing some of the first images of Mars captured by NASA’s Mariner 9 spacecraft.

Hartmann served on the mission’s imaging team, where he worked alongside Carl Sagan.

The newly assembled team at PSI also quickly went to work on a series of collaborative projects investigating the origin of the solar system.

That led Hartmann and Davis to write what turned out to be a famous paper, first presented in 1974, suggesting the moon was formed from the debris of a collision between the Earth and a giant primordial interplanetary body.

Davis said their idea “didn’t catch on really at all” at first, but since 1984 it has been widely recognized as the leading lunar origin theory.

Other early work by PSI has produced breakthroughs on the composition of asteroids and comets, the formation of planets and the use of impact craters to determine the age of planetary surfaces.

Another split

Through it all, the institute got along well with its parent company, which seemed to enjoy the prestige of being associated with PSI’s high-profile, NASA-adjacent scientific work.

But Davis said things began to change in the late 1980s, as SAIC grew and its defense work expanded.

“We could see that we would probably just be squished in this huge company in a few more years,” he said.

So in 1995, they broke away from SAIC and partnered with the fledgling San Juan Capistrano Research Institute, a California nonprofit launched by a former Jet Propulsion Laboratory researcher that Hartmann knew from his Mariner 9 days.

“We did that so we could be part of a true nonprofit,” Davis explained. “We were no longer Planets for Profit.”

But the transition proved painful at times. In the late 1990s, one of PSI’s founding scientists left for another job, and rumors began to swirl about the institute’s future.

Davis said he heard that officials at the UA even set aside some office space one year in anticipation of the scientists they expected to snatch up once PSI folded.

“They were just waiting for this to implode, but we hung in there,” he said. “We managed to get a few grants to keep body and soul together.”

By 2000, the Planetary Science Institute had all but absorbed its counterpart in San Juan Capistrano to become its own, independent nonprofit.

Sykes joined the institute in 2003 and took over as director in 2004, the same year PSI moved to its current location on Fort Lowell Road west of Campbell Avenue.

They had 19 researchers on staff by then, and they have continued to grow ever since, gradually taking over most of the commercial plaza they now call home.

“Scientists have joined us from universities, NASA centers and other government labs, and the private sector,” Sykes said.

The institute opened a second office in suburban Denver in 2016, though most of PSI’s scientific staff works remotely from 30 states and 10 countries.

Davis said their early experiences as part of larger organizations with offices scattered around the country taught them how to function in a distributed way.

“Once we became an independent nonprofit, that culture stayed with us,” he said. “That model has enabled us to grow substantially, because most of the scientists aren’t here.”

As Hartmann put it, quoting PSI’s longtime motto: “We were conceived by scientists, for scientists. We designed ourselves to work the way scientists work, which is radically different from the kind of corporate structure where you clock in at nine o’clock and out at five o’clock.”

“We basically say, do your best work the way you’d like to do it,” Davis added, “and as long as you’re getting grants, you can stay here.”

Next mission

Geophysicist Megan Russell joined PSI last March, after earning her master’s degree from the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

Geophysicist Megan Russell from British Columbia works out of the Colorado office of the Tucson-based Planetary Science Institute.

For her graduate research, she took a fresh look at old data collected by NASA’s Magellan spacecraft in the early 1990s and used it to show that Venus could be more volcanically active than previously thought.

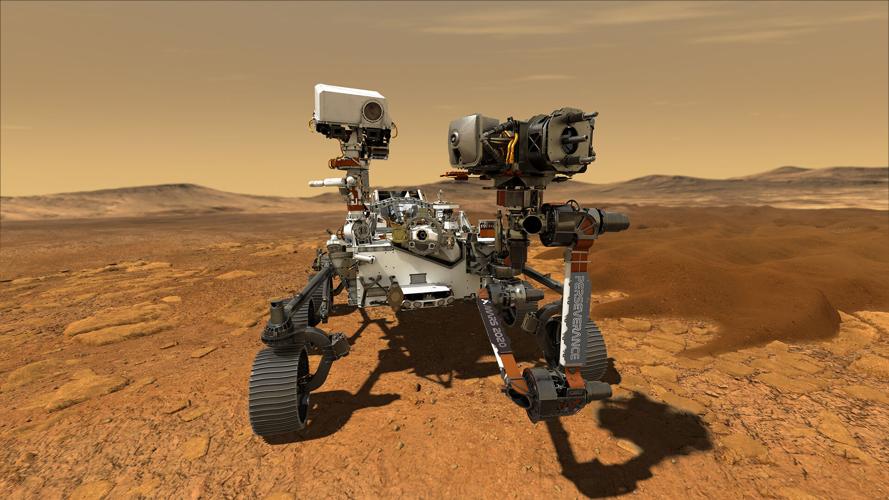

Now the Canadian research associate is focused on Mars.

From PSI’s Colorado office, Russell is analyzing radar images from the red planet as a member of the science team for the shallow radar instrument on NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter.

She said the institute and many of the researchers who work there are well known in the scientific community.

So far, it’s been a perfect fit for her, providing the chance to collaborate with a diverse group of fellow scientists and the freedom and flexibility to pursue her own projects.

“I was really interested in doing something outside of academia but still involved in research and mission operations,” she said.

Next up is a possible return trip to her old stomping grounds.

Russell is part of two instrument development proposals for a future robotic spacecraft bound for Venus. She expects to find out later this year if she — and PSI — will be selected to join the mission.

“To go back to Venus?” Russell said. “That would be so great.”