Astronomers have spotted what could be the largest comet on record, and the discovery has a strong Tucson connection.

The newly named Comet Bernardinelli-Bernstein is roughly 1.8 billion miles away and inbound toward the sun. Based on its brightness, experts believe it could be as much as 125 miles across — wider than the distance between Tucson and Phoenix.

It was found by University of Pennsylvania astronomers Pedro Bernardinelli and Gary Bernstein using a telescope operated by the National Science Foundation’s NOIRLab, an astronomical research institution headquartered in Tucson since 1959.

“It’s bigger than anything else anyone else has found, at least in terms of comets,” said Tod Lauer, a Tucson-based NOIRLab astronomer who was not involved in the discovery. “It’s one of those fun things — an object that came out of the blue.”

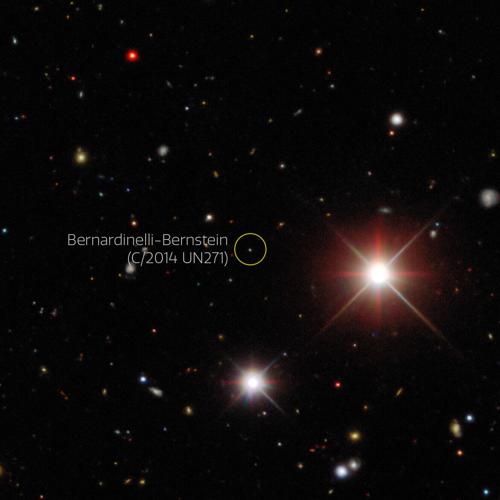

The comet appears as a point of light in ultra-high-definition images captured by the Dark Energy Camera mounted on the Víctor M. Blanco 4-meter Telescope at Cerro Tololo Inter-American Observatory in Chile.

The 570-megapixel camera was specially built for the international Dark Energy Survey, which has photographed almost one-eighth of the entire sky and cataloged hundreds of millions of galaxies as part of an effort to understand the shape of the expanding universe.

NOIRLab operates the telescope in Chile and the observatory on Kitt Peak, among other sites. It also curates the images collected for the Dark Energy Survey, a program the lab played a key role in starting.

Bernardinelli and Bernstein found the comet by using a supercomputer and some sophisticated identification and tracking algorithms to comb through 80,000 of those deep-space images in search of celestial bodies much closer to home: so-called Trans-Neptunian Objects that circle the sun beyond the orbit of the solar system’s most distant planets.

The comet shows up in images taken between 2014 and 2018, though there is no sign of a coma or tail normally associated with such icy bodies as they heat up on approach to the sun.

Since its discovery was announced June 19, astronomers have captured fresh images that do show a telltale cloud of gas and dust around the object.

“We have the privilege of having discovered perhaps the largest comet ever seen — or at least larger than any well-studied one — and caught it early enough for people to watch it evolve as it approaches and warms up,” Bernstein said in a written statement. “It has not visited the solar system in more than 3 million years.”

The comet’s current journey toward the sun began some 3.7 trillion miles away, in the distant Oort Cloud of icy relics cast off during the formation of the solar system.

This could be the largest Oort Cloud object ever discovered — roughly 20 times bigger than the asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago — so it’s a good thing it won’t be coming anywhere near Earth. Instead, it is expected to continue its approach until 2031, then swing back away from the sun before it reaches the orbit of Saturn.

Lauer said that should give us plenty of time to study it, perhaps shedding light on other Oort Cloud objects normally too far away to be seen.

It also serves as a valuable cautionary tale, since astronomers suspect that there may be many more undiscovered comets of this size lurking far beyond Pluto and the Kuiper Belt.

“There’s a little bit of scariness to it — something that big coming out of nowhere,” Lauer said.

Just don’t expect Comet Bernardinelli-Bernstein to light up the sky here on Earth.

“You won’t be able to see it with your eye or a pair of binoculars,” Lauer said. “You’ll still need a powerful telescope.”