For well over a century, the Corbett Irrigation Ditch carried water from Tanque Verde Creek to the old Fort Lowell neighborhood, where it nourished farmland and helped to sustain a thick forest of native velvet mesquite trees.

Now a group of residents, historians and conservationists have launched a campaign to restore the trees and fill the ditch with water again for the first time since it mysteriously ran dry roughly a decade ago.

“We came together as a group last year to really get this moving,” said Colleen Sackheim, a Fort Lowell Historic District Advisory Board member whose neighborhood roots go back almost 50 years. “We’re in the information-gathering stages.”

Based on the research so far, the irrigation ditch appears to date to the 1860s, making it about five years older than the actual fort at Fort Lowell. The mesquite grove goes back a lot further than that.

The stand of trees represents one of the last surviving remnants of a vast mesquite bosque that once covered the lowlands all along the Rillito River, but time may be running out for the forest.

“It’s currently dying,” said Harold Thomas, associate director of Watershed Management Group, a local conservation nonprofit. “It’s been dying for the past five years or so.”

From the west side of Craycroft Road, just south of the Gregory School, the damage is plain to see. The banks of the empty irrigation canal are lined with the skeletons of dead mesquites, some with trunks several feet across.

“The water’s just not making it to that ditch,” Thomas said. “We would like to see the ditch flowing again to support the velvet mesquites there.”

The restoration effort is being led by residents of the Old Fort Lowell Neighborhood with help from Watershed Management Group and the Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation.

Their first order of business: “Figure out what stopped the water from flowing,” Thomas said. “Before this can go anywhere, we need to figure out what’s happening.”

Barry Spicer and Colleen Sackheim, residents of the Old Fort Lowell Neighborhood, stand in the Corbett Irrigation Ditch, which mysteriously ran dry about a decade ago. The ditch appears to date to the 1860s, making it older than the fort itself.

An acequia oasis

Taking their cues perhaps from ancient Hohokam irrigators, 19th-century farmers and ranchers along the Rillito built a tangle of flumes and canals to tap into a nearby quirk of geology. Beneath Tanque Verde Wash lies an impermeable layer of rock that stretches from just upstream of the confluence with Pantano Wash to the mouth of Sabino Canyon. Groundwater, replenished by rain and snow in the Catalinas, perches on this underground shelf, close enough to the surface to be siphoned and channeled downhill to waiting fields.

“That was the headwaters of about 30 different irrigation ditches in the 1890s up into the mid-1910s,” said Barry Spicer, who has spent most of his life in the Old Fort Lowell Neighborhood.

Those gravity-fed canals, known as acequias in Spanish, provided reliable water for eight to 10 months of the year, though the diversions were prone to washouts during seasonal floods on the Tanque Verde, Pantano and Rillito.

The Corbett Irrigation Ditch was named for the Franklin Corbett family, which ran a small dairy near Swan Road. Locals also sometimes referred to it as the Douglas Ditch, after the L. W. Douglas family and its Pantano Farms and polo field near Fort Lowell and Swan.

The canal and the trees surrounding it have been a fixture in Spicer’s life.

His parents, both anthropologists, moved into the Fort Lowell neighborhood in 1946. As kids, he and his siblings used to play along the ditch in the shade of the mesquites.

One night, Spicer said, he went down into the trees and laid down on his back to cure himself of his childhood fear of the dark. Then when he was 15, the future wildlife biologist conducted his first scientific study on the birds of the bosque, before the area was developed.

“One of the things that I personally think we tend to forget, even when we're talking about history, is natural history. Those mesquite bosques and those mesquite woodlands, all of those biological communities, were here long before human beings were,” Spicer said. “The environmental history is as strong, as important, as significant as the cultural history.”

Saving trees

that remain

Historical records suggest the Corbett Irrigation Ditch once stretched for more than two miles, irrigating fields along the Rillito’s southern floodplain. The water collected in an artificial pond at Hill Farm before continuing west to present-day Swan Road to join other irrigation canals.

Spicer said he used to splash in the pond with the Hill children when he was a kid, but it was filled in about 40 years ago as cropland was converted to homes. Parts of the old irrigation ditch have since been channeled into underground pipes by developers.

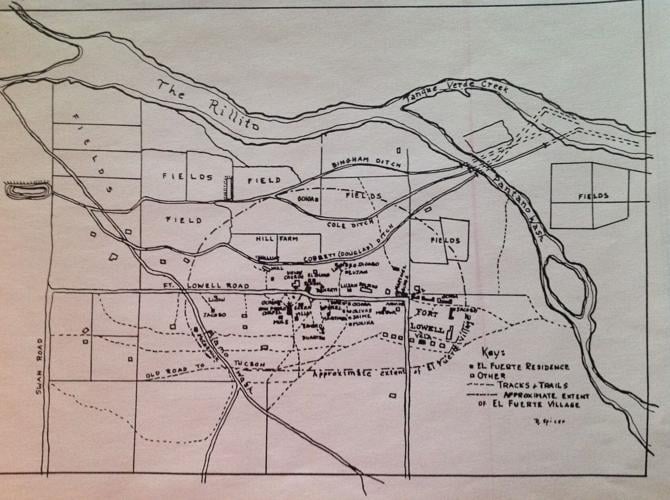

A hand-drawn map by long-time Fort Lowell neighborhood resident and historian Rosamond Spicer shows the approximate location of the Corbett Irrigation Ditch and other historic canals that supplied farms on the south side of the Rillito River.

Not everywhere, though. The Placita Del Mesquite subdivision northwest of Craycroft and Fort Lowell Road was built around the ditch, with many of its homes backing up to its banks.

“I believe when these homes were built, it was not expected that it would stop flowing," said Carol Maywood, a retired physician turned neighborhood historian. "I think the belief was that it would continue to flow and give a lot of these homes a lovely little stream.”

Maywood said the water was still running when she moved into her home on Placita Del Mesquite in 2001, but the ditch seemed to run dry for good about a decade ago. That’s when the homeowners stepped up.

“The residents have been very careful to preserve the trees … and the banks of the ditch to keep it in its original condition if possible,” Maywood said.

As a result, some portions of the canal there remain lush and green, with towering mesquites like the ones that once dominated the whole area.

Meanwhile, nearby, a few new trees have sprung up to replace ones that have been lost.

Watershed Management Group recently partnered with residents along the ditch and staff members at the Gregory School to plant about three dozen locally sourced velvet mesquite saplings where the forest used to be. Property owners are watering those plants for now, but eventually the trees could be irrigated with harvested rainwater or flows from the ditch.

“I really appreciate the people who are working to try and make this happen,” Maywood said.

Seeking answers

At the moment, the restoration group is searching for a technician who can inspect the old irrigation system, determine why it stopped working and figure out how —or maybe if — it can be fixed.

Thomas thinks the works may have been clogged by debris or inadvertently severed by construction along Pantano Wash, possibly for the Chuck Huckelberry Loop.

Extended drought or groundwater pumping closer to the head of the ditch might also be to blame.

Spicer said they hope to be able to get the water flowing again, even sporadically, to help the mesquite forest, but a lot of unanswered questions remain, including how they will pay for any work that needs to be done.

“We would like to see it (happen) as soon as possible, but there are so many variables," Spicer said. "We don’t know enough yet to make a plan with dates. We don't even know all the questions that we need to answer.”

Time may be running out for native velvet mesquites once sustained by the Corbett Irrigation Ditch, which carried water from Tanque Verde Creek to the Old Fort Lowell Neighborhood. The first order of business: "Figure out what stopped the water from flowing," says Harold Thomas, associate director of Watershed Management Group.

If the flow cannot be restored, Thomas said other work could be done to channel seasonal storm runoff to the area to support the bosque.

He said the county officials he has spoken to so far seem supportive of the restoration effort, so long as it is done with care. The last thing the county — or anyone else — wants to do is put water back in the ditch that could end up flooding someone’s property in the area, Thomas said. “There are some homes in there that probably weren’t there before.”

Spicer said they also want to avoid creating pools of water that could become a breeding ground for mosquitoes.

The restoration project meshes nicely with Watershed Management Group’s overall mission of protecting desert ecosystems. The nonprofit promotes urban rainwater harvesting and “green street” projects aimed at conserving water, beautifying neighborhoods and improving the environment.

Within the next 50 years, Thomas and company hope to bring back perennial flows to the Santa Cruz, Lower Sabino Creek, Tanque Verde Wash, and even the Rillito in partnership with other community and governmental organizations.

Historic waters

The Corbett Ditch and the trees surrounding it perfectly encapsulate the often-deep connection between historic resources and natural ones, especially in a desert community like Tucson, says Demion Clinco, the CEO of the Tucson Historic Preservation Foundation.

Taken together, Clinco said, the ditch and the trees help tell the foundational story of “our relationship with water.”

“Historic preservation isn’t about a single building. It’s about our whole built environment,” he said.

Though the ditch is not currently listed on any historical register, Clinco thinks it certainly qualifies. It’s not some ornamental feature, it’s a tangible link to our agricultural heritage. “It’s a historic piece of infrastructure that brought water to the surface,” he said.

Clinco has a personal stake in the project.

“I grew up in that neighborhood, and I remember going to that ditch as a kid. You couldn’t swim in it, but you would go to it,” he said. “It really was a forest, and you really got a sense (from it) of the giant mesquite forest that once ran through the center of the Tucson valley.”

Clinco said restoring a piece of that forest and the water that once sustained it fits in perfectly with Mayor Regina Romero’s pledge to plant 1 million trees in Tucson by 2030 and the longer-term goal by Watershed Management Group and others to get water back into the Rillito someday.

“You have to start somewhere,” he said. “Why not start with this little acequia and see what happens?”