Citing its own serious financial troubles, the Arizona Historical Society board voted Friday to end its operating agreements for the Fort Lowell Historical Museum and the Downtown History Museum.

The two facilities have been closed since April 1 due to the pandemic. If they hope to reopen, they will need someone else to run them.

“This is not an easy vote,” said board president Linda Whitaker after the near-unanimous decision, “but we have to look at the data and react accordingly.”

The board also voted to end the society’s 10-year-old agreement with Arizona State Parks and Trails to operate the Riordan Mansion State Historic Park in Flagstaff. Nearly all of the public comment at Friday’s meeting concerned the early-20th-century mansion.

The decision came after society board treasurer James Snitzer delivered what he described as a “doom and gloom” financial update on the organization.

Without improved revenue and major operational changes, he said, the society’s overall budget could shrink to “a shutdown level” within two years, forcing it to close the eight museums and historic sites it owns around the state.

Friday’s action was “small potatoes” compared to what lies ahead, Snitzer said. “We’ve got some bigger fish to fry as a board later on.”

Arizona’s oldest historical agency has operated the Downtown History Museum for the past 20 years under an agreement with Wells Fargo, which owns the bank building where the exhibits on Tucson’s past are housed at 140 N. Stone Ave.

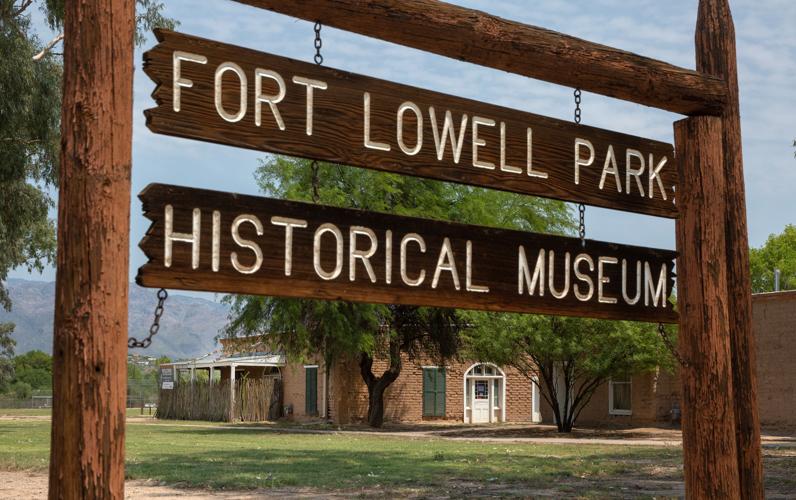

The Fort Lowell Museum was developed by Pima County in 1963 to mark the site of the military post that operated there in the late 19th century. The city acquired the museum in 1984, and the Historical Society has operated the facility since 1987.

Under the agreements, the society provides direct financial support, marketing and administrative services to the two Tucson museums, neither of which charge admission.

Most of the artifacts inside the two museums are owned by the Historical Society. Once the operating agreements end, the society will have to take custody of those items, though they could be made available for loan or exhibit in the future if new operators are found.

The Fort Lowell Historical Museum marks the site of the military post that operated there in the late 19th century. The Arizona Historical Society had run the facility since 1987.

Assistant City Manager Albert Elias said Tucson officials are exploring some options and talking to potential partners in hopes of keeping the Fort Lowell Museum open. “We do think that’s important and worth doing,” he said.

City Councilman Paul Cunningham envisions reopening the museum as part of a larger restoration project that would include other parts of the old fort and nearby historic properties.

It could be a year before anything happens, he said, “but we’re not going to allow the property to go dormant for very long.”

Frank Flasch, vice president of the Old Fort Lowell Neighborhood Association, hopes something can be worked out.

“We’re very disappointed that the Historical Society is pulling out. The museum has meant a lot to the neighborhood,” Flasch said. “We’re looking for different ways we can keep it going.”

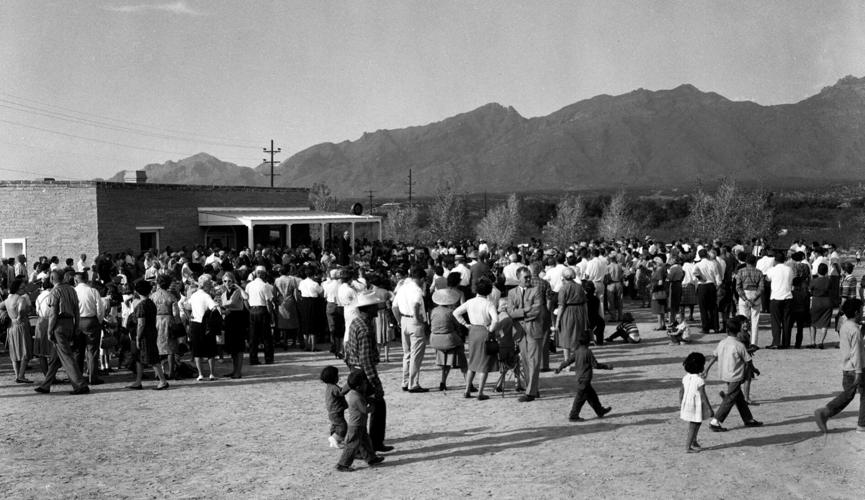

Visitors crowded around the reproduction of the new commanding officer’s quarters during a dedication of the Fort Lowell Historical Museum on Nov. 11, 1963.

The future of the Downtown History Museum is far less certain.

James Burns, executive director of the Historical Society, said he got word just before Friday’s meeting that Wells Fargo intends to vacate the entire bank building where the small collection is housed.

Historical Society board members were originally set to vote on canceling their operating agreements in Tucson and Flagstaff in August, but the decision was delayed after local groups complained about being blindsided by the move.

Board president Whitaker said no one should have been caught off guard. Though the pandemic has made things worse for everyone, the society has been talking about ending these agreements for several years now.

“I don’t think we were taken seriously,” she said. “We can’t afford not to act. As a board, we are compelled to do something about this.”