As shutterbugs know all too well, light is the key ingredient of any photograph.

But where can you find the illumination you need when your camera is almost 3 billion miles from home and pointed at the dark side of the solar system’s most distant planet?

A research team led by Tucson-based astronomer Tod Lauer found a clever solution to that problem hidden away in images captured by NASA’s New Horizons spacecraft.

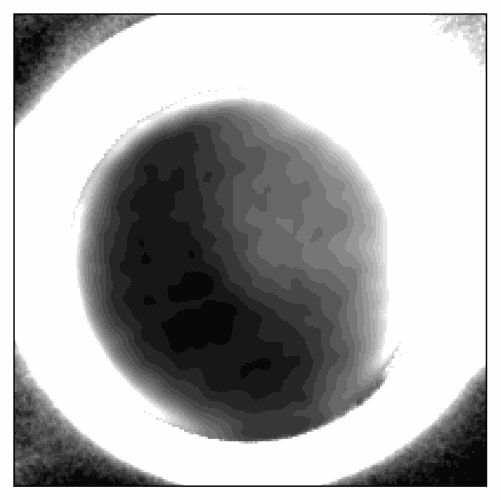

Lauer and company used faint sunlight reflecting off of Charon, Pluto’s largest moon, to tease landscape details from an otherwise unlit portion of the dwarf planet’s southern hemisphere.

Lauer said it was a little like trying to see in the desert under the light of a crescent, first-quarter moon.

“That’s not a lot of light to work with,” he said.

The resulting image and their scientific interpretation of it was published Oct. 20 in The Planetary Science Journal.

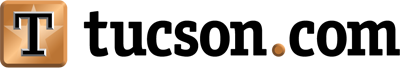

The picture was pieced together using 360 parting shots of Pluto taken by New Horizons as it streaked away from the icy planet in 2015.

The images were badly overexposed because the planet was backlit by the sun, creating a halo of glare through Pluto’s atmosphere that was a thousand times brighter than light from Charon, Lauer said.

Study co-author and New Horizons co-investigator John Spencer, from the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, compared the effort to “trying to read a street sign through a dirty windshield when driving toward the setting sun, without a sun visor.”

Lauer works for the National Optical Infrared Astronomy Research Lab, a National Science Foundation research institution headquartered in Tucson since 1959. His NOIRLab work usually focuses on extra-galactic and deep space astronomy, but he loves a good image processing puzzle.

Lauer said he “took a crack” at the dark-side images when New Horizons first beamed them back to Earth in 2016, but a number of technical problems stood in his way.

He revisited the data in 2019, using some specially designed algorithms over several months to refine the images, filter out the sun’s glare and reconstruct what was missing.

“I liken it to cooking an artichoke,” Lauer said. “There’s a lot of work involved for not very much food.”

He acknowledged that the finished picture probably “looks like a fuzzy mess to non-astronomers,” but it has revealed some tantalizing details on Pluto that wouldn’t otherwise be visible for decades.

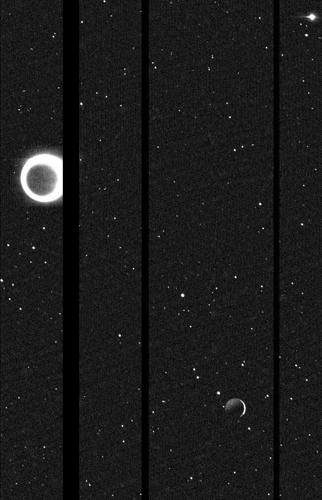

Among them is a bright area that researchers believe could be frozen nitrogen or methane, similar perhaps to the now-famous heart-shaped plain known as Tombaugh Regio that dominates the northern hemisphere. That feature is named for Clyde Tombaugh, the astronomer who discovered Pluto in 1930 from Lowell Observatory in Flagstaff.

The new image also offers clues about slow seasonal changes to the surface of the planet.

For example, the area around the south pole appears to be covered in material that is far darker than what New Horizons found in the northern hemisphere. Researchers suspect the color difference could be the residual effect of the planet’s “southern summer,” which ended about 15 years before the spacecraft arrived.

Lauer said the southern hemisphere is now entering the dark of winter and won’t see the sun again for about 60 Earth years. (Technically, the dwarf planet doesn't have a permanent dark side, just really long, dark winters.)

Without a follow-on mission by another spacecraft, researchers will have to wait until sunlight returns to that part of Pluto, decades from now, to verify the accuracy of the new photo plucked from the dark.

“Was I right after all this image processing?” Lauer said. “They can check my work in 2080 or so.”