Scientists from the University of Arizona and around the world just unveiled the largest map of the universe ever created, though it probably won’t help you much on your next road trip.

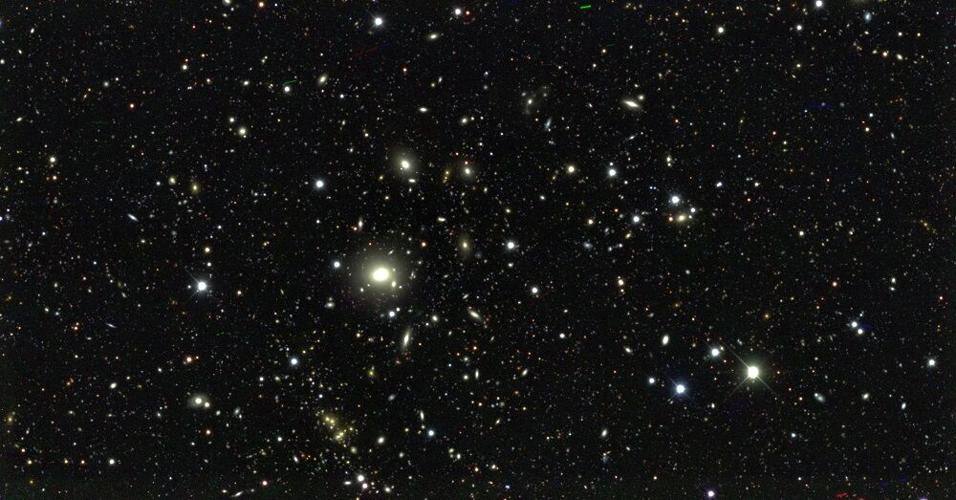

The map by the international Dark Energy Survey spans more than 7 billion light-years and takes in 226 million galaxies.

It was compiled by some 400 scientists from 25 institutions in seven countries using three years’ worth of images captured from a mountaintop telescope in Chile by one of the world’s most powerful digital cameras.

The results provide the most precise measurements yet of the universe’s composition and growth, helping scientists better understand the distribution of matter since the Big Bang roughly 14 billion years ago.

“It’s exciting to quantify how our universe has evolved over time,” said Elisabeth Krause, a UA assistant professor of astronomy and physics, in a written statement. “Basically, we are looking at the spatial distribution of galaxies at different ages of the universe, and we track how this distribution has changed over time.

“It’s like watching the universe grow up, starting from when it was only one-third of its age today,” said Krause, who provides scientific leadership for the Dark Energy Survey.

Researchers published their findings Thursday as part of a series of 29 scientific papers. Their results are based on photographs of the night sky taken through a 4-meter telescope by the specially designed Dark Energy Camera, which captures images at 570 megapixels.

By comparison, the camera on the newest Apple iPhone has a resolution of 12 megapixels.

Video by Fermilab via YouTube

Over the past six years, the Dark Energy Survey and its 4-ton, $35 million camera have covered almost one-eighth of the entire sky and cataloged hundreds of millions of objects.

The results released Thursday draw on data from the first three years of the survey to create the largest and most precise maps yet of the distribution of galaxies in the universe in relatively recent times.

Since the Dark Energy Survey studies nearby galaxies, as well as those billions of light-years away, its maps provide both a snapshot of the universe’s current large-scale structure and a look back at how that structure has evolved over the course of the past 7 billion years.

Ordinary matter makes up only about 5% of the universe. The other 95% of, well, everything is composed of dark matter and dark energy, two mysterious and invisible phenomena that cosmologists believe play a role in binding galaxies together and accelerating the expansion of the universe.

Krause heads up the survey’s science committee with Scott Dodelson, chair of the physics and astronomy department at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

UA faculty, students and postdoctoral researchers in the Arizona Cosmology Lab have conducted scientific analysis for the survey.

“This is a fantastic dataset to work on,” said Xiao Fang, a postdoctoral researcher at UA’s Steward Observatory and a lead author of one of the latest Dark Energy Survey papers. “For junior researchers like me, it is the ideal opportunity to develop and implement new ideas and to test some of the most famous theories in cosmological physics.”