Asteroid hunters from the University of Arizona set another record in 2020, despite a pair of earthly threats to their early-warning telescopes high in the Catalina Mountains.

The NASA-funded Catalina Sky Survey identified 1,548 new near-Earth objects last year, the most productive year in the decades-old search for dangerous space rocks in our immediate cosmic neighborhood.

To reach the new mark, survey members had to overcome a weeklong coronavirus shutdown in the spring. Then came the massive Bighorn Fire, which chased them off the mountain for three weeks and nearly burned down their telescopes.

“It was a good year discovery-wise,” said Eric Christensen, who directs the survey through the UA’s Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. “It’s going to be tough to beat.”

They’re off to a great start in 2021. Since Jan. 1, observers have found 242 more previously unknown space rocks within about 120 million miles of Earth.

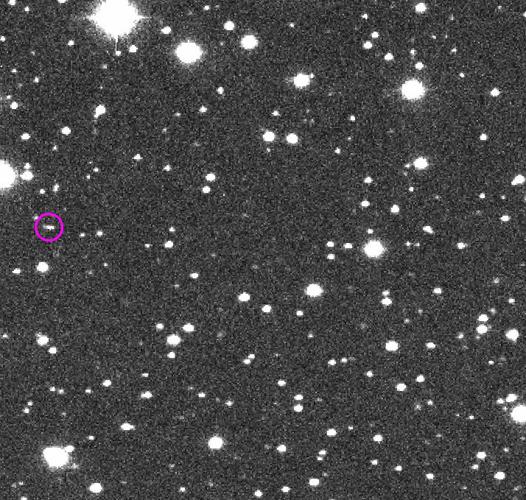

In this sequence of four images published on June 30, 2017 and taken during one night of observation by NASA’s Catalina Sky Survey near Tucson, Arizona, the speck of light that moves relative to the background stars is a small asteroid that was, at the time, about as far away as the moon. This asteroid, named 2014 AA, was the second one ever detected on course to impact Earth. It was estimated to be about 6 to 10 feet (2 to 3 meters) in diameter, and it harmlessly hit Earth’s atmosphere over the Atlantic Ocean about 20 hours after its discovery in these images.

Watching out for the big one

The search for nearby objects is about security as much as discovery.

Our planet gets hit with space debris all the time. Anyone who has seen a shooting star has seen one of these collisions.

Christensen said most of the stuff is the size of a pebble or a grain of sand, though a rock at least 3 feet across will typically hit our atmosphere once every few weeks.

It’s only the really big stuff that we need to worry about.

The Catalina Sky Survey is part of a global network designed to find and track what are known as “potentially hazardous objects,” namely any asteroids or comets larger than 460 feet wide that cross the Earth’s orbit.

About 2,200 such objects have been identified so far, including 157 potential killers ranging in size from just over half a mile to more than 4 miles in diameter.

The asteroid that wiped out the dinosaurs 66 million years ago was about 6 miles wide.

“We need to be doing more”

Fortunately, Christensen said such large, “civilization-defining” impacts are exceedingly rare — something on the order of once every 100 million years or so.

And with enough advanced warning, he said, a mission could be mounted to try to nudge an incoming asteroid just enough for it to miss the Earth.

None of the large objects currently being tracked are projected to hit us, at least not within the next century.

But there are still a lot of rocks out there waiting to be found. By some estimates, only about one-third of all potentially damaging near-Earth objects have been identified, leaving roughly 15,000 large asteroids and comets still to be discovered.

“I think the consensus is that we need to be doing more, but we’re doing what we can,” Christensen said.

Congress has set a goal of identifying at least 90% of potentially hazardous objects.

A future space mission led by UA professor Amy Mainzer and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory is expected to speed progress toward that goal.

Set for launch as early as 2025, the unmanned spacecraft known as NEO Surveyor will use highly sensitive heat-sensing cameras to track near-Earth objects.

“That is likely to be a much more efficient way” of spotting asteroids, Christensen said.

The NASA-funded Catalina Sky Survey identified 1,548 new near-Earth objects last year, the most productive year in the decades-old search for dangerous space rocks.

Sky survey launched in 1998

The current push to identify potentially dangerous space rocks began in earnest about 25 years ago, after Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 broke apart and crashed into Jupiter in July 1994. That spectacular collision served as a reminder about the hazards posed by interplanetary debris.

UA research scientist Steve Larson launched what would become the Catalina Sky Survey in 1998, with the help of two volunteer undergraduate astronomy students. They would photograph the night sky from a telescope on Mt. Bigelow, then develop the film and comb through the images.

“It was very labor-intensive back in those days,” Christensen said.

Advancements in optics, computers and software have dramatically improved the discovery rate since then. Early on, sky surveyors might find a few new asteroids or comets each year.

“These days, we are finding a few every night,” Christensen said.

Twenty years ago, there were fewer than 1,500 known near-Earth asteroids. Today that number stands at almost 25,000, roughly 12,000 of which were found by the team from Tucson.

No other survey in the world even comes close.

“We still discover about half of the near-Earth asteroids that are discovered every year,” Christensen said.

Names that live on in the stars

Along the way, the survey team has named a few hundred of its discoveries after some of their worthy predecessors and contemporaries.

Members of the UA-led OSIRIS-REx asteroid sampling mission all have asteroids named after them, as do other pioneering members of the university’s world famous astronomy department.

Christensen said his namesake space rock is “fairly ordinary as asteroids go,” except that it was discovered on his birthday by one of his survey mates.

Christensen also has his name on some two dozen comets, though not out of vanity. Under the arcane rules that govern such things, comets are automatically named for the astronomers who discover them.

The Catalina Sky Survey operates with a staff of 14, including seven full-time observers who scan the night sky using three telescopes in the Catalinas.

Two other telescopes run by the UA’s Steward Observatory, including one on Kitt Peak, are used periodically for follow-up investigations.

There are two observers stationed on Mt. Lemmon and Mt. Bigelow on any given night. On-site lodging allows them to stay up there for the duration of their shifts, which typically last three to six nights at a time.

The Bighorn Fire shut down the Catalina Sky Survey for about three weeks last summer and came within a few yards of the observatory, but firefighters saved all of the telescopes.

Fire forced observatory evacuation

No one from the team was allowed on the mountain from mid-June through early July, when the Bighorn Fire forced the evacuation of Mount Lemmon and Summerhaven.

“It was a very nerve-wracking three weeks,” Christensen said. “At that point, there was nothing we could do. We could watch the news and pray, basically.”

He said the flames ended up burning to within a few yards of the mountain-top observatory, but not a single telescope was damaged, thanks to the “incredible efforts” of firefighters.

“We lived to survey another day,” Christensen said.

They were even able to make up for lost time later in the summer, once the fire was out.

Monsoon season is usually a down time for them, with regular cloud cover over the Catalinas that forces them to cut back operations and focus on scheduled maintenance.

Last year, though, “the monsoon never showed up,” so they just kept working, Christensen said.

Mission funded for 3 more years

This year’s crop of 1,548 new space rocks includes 192 asteroids that are at least 450 feet in diameter. Of those, 42 rank as potentially hazardous because of orbits that could bring them within 4.8 million miles of Earth, a close call by celestial standards.

The largest discovery is more than three-quarters of a mile wide. The smallest could fit on top of the average kitchen table.

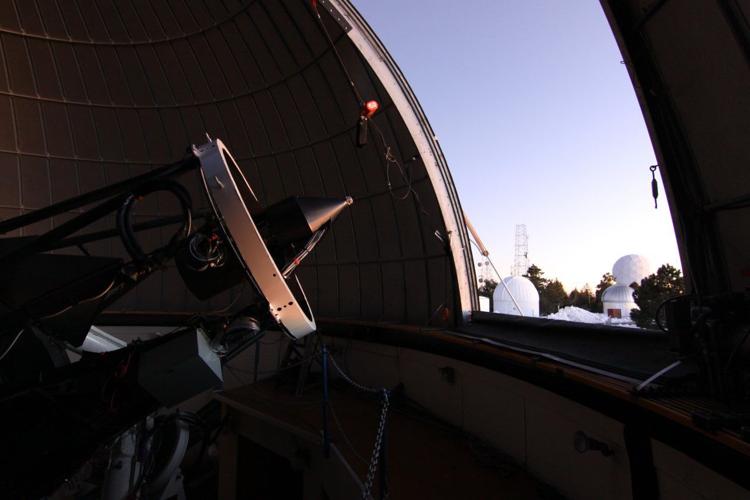

An open telescope dome looks out on the Mt. Lemmon observatory, where the University of Arizona’s Catalina Sky Survey searches nightly for potentially dangerous space rocks.

NASA recently awarded the Catalina Sky Survey another $8.7 million to sustain the operation for three more years and help pay for equipment and software upgrades that should lead to even more discoveries. There are also plans to add two more full-time staff members to their mountain-top team of cosmic night watchmen.

Could all this end up saving humanity some day? It’s highly unlikely it will ever come to that, Christensen said, but the stakes are high enough to justify the effort.

“Knowing who your neighbors are is important, especially when your neighbors are going to throw rocks through your windows,” he said. “We can do it, we know how to do it, and it’s a very important thing to know.”