When Alberto Ríos was a University of Arizona student in 1970 or ’71, he wandered into the cozy cottage that housed the decade-old Poetry Center. He relished selecting books from the shelves and discovering meaningful, inspirational lines. No one told him what to read or not read.

“I would go there because I wanted to be there,” says Ríos, a Nogales, Arizona, native who is Arizona’s poet laureate.

“You could go there to find your internal compass,” says Rios. “It (the Poetry Center) spoke to you. It sang to you.”

The Poetry Center, on the cusp of its 60th anniversary, still speaks, but it has deeper, broader voice.

The Poetry Center is a gathering place with lively discussion, sharing experiences and exchanging ideas. It’s a space where academics pore over can’t-be-found-elsewhere materials, and everyone is welcome to explore recordings, books and exhibits.

The COVID-19 pandemic forced the center to put programs on pause and close the doors a few months before its diamond anniversary celebration, says Tyler Meier, UA Poetry Center executive director. Visiting poets are not traveling and much of the center’s staff are working in a digital mode, he says.

The center created a constellation of anniversary-related online events. A 360 virtual tour, an exhibit of Arizona poets and a peek at 60 rare books are a few of the activities available with a click of the mouse.

The final anniversary star appears at 6 p.m. Tuesday, Nov. 17. Leading poets will discuss the future of poetry and speakers will toast the center and share its accomplishments during an online fundraiser. Learn more at tucne.ws/pc60.

THE COTTAGE THAT COULD

The poetry cottage that Ríos stepped into as a teen was created by novelist, poet and philanthropist Ruth Walgreen Stephan (1910-1974), the daughter of drugstore chain founder, Charles R. Walgreen.

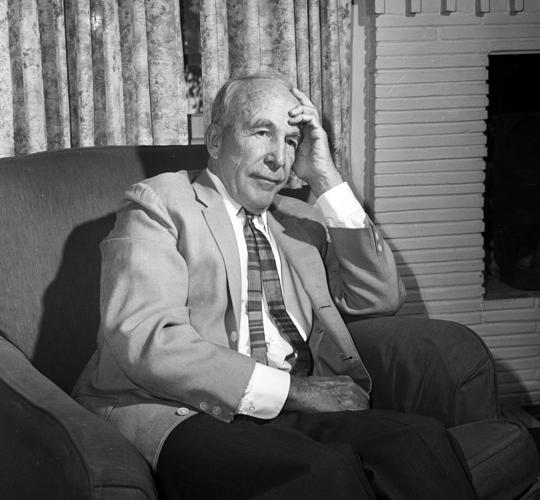

Stephan had diverse interests and was “very into anthropology,” says Richard Shelton, a poet who has been associated with the Poetry Center since its founding. From 1961 to 1965, Stephan and Shelton teamed up to edit two spoken anthologies of poems and fiction of U.S. literature of the 19th and 20th centuries. UA produced the record sets.

In the 1950s, Stephan spent winters in Tucson, says Shelton. She wrote in a bungalow on North Highland Avenue owned by her friend, Ada Peirce McCormick (1888-1974).

Stephan purchased that bungalow and an adjacent one. Stephan donated the two bungalows to the UA for the center’s library and to house visiting poets. She also seeded the collection with several hundred volumes of poetry.

Stephan’s vision was a place where books were accessible and a “place in the desert where poets come and stay,” says Meier.

Stephan, who wanted the collection to have national and international significance, and her mother, Myrtle Walgreen, funded an acquisitions endowment.

Robert Frost (1874-1963), the author of “The Road Not Taken” who read at President John F. Kennedy’s inauguration in 1961, read at the dedication of the Poetry Center on Nov. 17, 1960.

Shelton says his connections with poets and writing groups, coupled with Stephan’s financial backing enabled the young poetry center to attract “all the big names,” such as Allen Ginsberg (1926-1997), the Beat Generation poet whose poem “Howl” was a counterculture anthem.

“The center has become far, far beyond anything we could have imagined,” says Shelton.

The Poetry Center is one of the most “important places for poetry in the country,” says Joy Harjo, U.S. poet laureate who taught at UA from 1988 to 1990.

DEEP CONNECTIONS

Poetry, one of the world’s oldest art forms, is more than a “report of the news, of what’s happening right now,” says poet Alison Hawthorne Deming.

Poetry is a measure of human condition; it adds a deeper resonance and connection to events, says Deming, who was director of the Poetry Center from 1990 to 2002. She predicts powerful poetry will emerge from the pandemic and related isolation.

The Poetry Center is “the heart of the University of Arizona campus,” says Harjo. It is a beacon of understanding and compassion.

Eighteenth-century Scottish poet Robert Burns composed the text for "Oh My Luve’s Like a Red, Red Rose" to depict the immense longing and pass…

“When you walk into the Poetry Center, you are in the presence of more than 5 million poems,” says Alain-Philippe Durand, dean of the UA College of Humanities. “That’s a profound experience that isn’t possible in the same way anywhere else.”

The Poetry Center has one of largest collections of contemporary poetry in North America. Its collection contains more than 50,000 volumes of poetry as well as chapbooks, journals and periodicals, and 5,000 photographs.

The reading series launched in 1962 with Stanley Kunitz (1905-2006), who won the 1959 Pulitzer Prize in Poetry and was the U.S. poet laureate in 1974 and again in 2000. The center has hosted and recorded major U.S. poets ever since.

You can listen and watch those readings through Voca, voca.arizona.edu, the center’s audio-visual archive. It houses over 1,000 recordings of poets reading their work, says Sarah Kortemeier, who oversees the Poetry Center Library. Readings between 1963 and 1999 are audio; readings after 2000 are video.

In the early years, visiting writers could stay in the Poet’s Cottage, one of the original little houses. Writers staying in the cottage often signed the kitchen wall and inscribed pithy observations, says Shelton.

The bungalows fell for the 1989 widening of Speedway and the center moved into two university-owned houses on North Cherry Avenue. In 2003, campus construction forced the center to move to temporary digs at 1600 E. First St.

When Peter W. Likins came to UA to be its 18th president in 1997, he says he assessed the university’s “strengths and opportunities” and the Poetry Center was among the programs with both.

It had intellectual support and a national and international reputation, and needed a space reflective of its prominence, Likins says.

Rejecting ideas to reuse existing space, Likins announced in 2004 that the Poetry Center building would be named for Tucson arts advocate and chair of the center’s development committee, Helen S. Schaefer. Construction began May 2006 and was completed August 2007.

The 17,500-square-foot Schaefer Building, designed by architect Les Wallach and his team at Line and Space Architects, is two buildings connected by a breezeway. It’s located at 1508 E. Helen St.

An homage to the cottage that housed visiting poets, Lois Shelton Poet’s Cottage is a writer’s retreat, a studio apartment in the Schaefer Building. There is no writing on the wall, however; writers are asked to sign and share sentiments in a guest book.

The apartment is named for Shelton’s wife, Lois, who died in 2015.

Director of the Poetry Center from 1970 to 1990, she is credited with elevating the center’s reputation, adding to the library collection and being a “perfect hostess” to visiting poets and at events, Shelton says.

In addition to shelves of books, the facility’s gallery spaces are filled with permanent exhibits and, in nonpandemic times, displays curated from the center’s archival collections. The center’s author files include records and correspondence pertaining to poets like Frost and Ginsberg.

The climate-controlled rare book room holds and preserves “priceless books to make them permanently available” says Durand. A weathered copy of Stephan’s first book of poetry resides in the rare book room.

An outdoor amphitheater hosts community events and when the floor-to-ceiling glass doors of the Dorothy Rubel Room, home of the UA Humanities Seminars Program, are opened, as many as 250 people can gather.

There’s a spot for children and there are tables, comfy chairs and a garden for serious study or reading for enjoyment and enlightenment.

OUTSIDE THE DOORS

“The Poetry Center has never been content to exist exclusively within the proverbial ivory tower; instead it has become a critical part of the cultural fabric of Tucson and the literary world at large, with an incredible slate of programs, educational projects and community outreach,” says Durand.

The reading series — bringing poets in — is integral to the Poetry Center’s programming and has outreach programs for students and schools, sending poets into classrooms and offering creative writing workshops.

Poetry Center launched its inaugural season of podcast “Poetry Centered” to reach out beyond its doors. Find more about the Poetry Center’s podcast “Poetry Centered” at https://poetrycentered.buzzsprout.com/.

The Poetry Center administers the grant to support Shelton’s Arizona Prison Writing Project, a program of writing workshops with inmates that Shelton founded in 1974 and is a model for other prison writing programs. The “Walking Rain Review,” a publication of the work of current and former inmates will be available for free at the Poetry Center.

The Poetry Center has a grant from the Art for Justice Fund for a three-year project to commission new work on mass incarceration in the United States.

“Poetry Center documents and celebrates the work that poems do — teaching us about both our experiences and our imaginations,” says Durand.

You can go to the library and find all the information in the world, says Ríos. But the Poetry Center is where “ideas incarnate, where they come to sit down and have coffee.”

Ríos says the Poetry Center helped him become a “thinking human being.”