When morning sunlight pours through the east-facing windows at the University of Arizona Poetry Center, it filters through poet Richard Shelton’s words, which are written in binary code cut-outs on a parallel stone wall.

“If I stay here long enough, I will learn the art of silence,” reads the code, which is a line from Shelton’s poem, “Desert.”

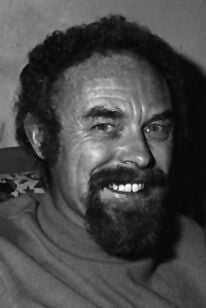

Shelton

Both the Richard Shelton Wall and the larger 17,000-foot poetry center in the Helen S. Schaefer building, which Shelton helped raise $5 million to build in 2007, are physical symbols of his life’s work to make the UA and Tucson a hub for creative writing as an inclusive art form people from all backgrounds — including convicted criminals — can produce.

When Shelton, 89, died Nov. 29 after several years of declining health, the poetry center took on an additional purpose as a permanent memorial to the prolific writer affectionately known by some as the Poet Laureate of the Sonoran Desert.

‘Premier Southwestern poet’

“He was the premier Southwestern poet and one of the premier poets of his generation in the country,” said writer Bob Houston, Shelton’s longtime friend and colleague in the UA English Department. “He was a wonderful storyteller. He was a very strong environmentalist, a lover of the desert and everything it represents.”

Shelton, who authored a dozen books of poetry and nonfiction — much of it about desert life — was born far from Tucson, in Boise, Idaho, in 1933.

He grew up poor and turned to reading as an escape from the stressors of poverty. In 1951, Shelton left Idaho to attend Harding College in Arkansas. Two years later, he transferred to Abilene Christian College in Texas.

There he began dating Lois Bruce, a classically trained vocalist, and obtained a bachelor’s degree in English. The couple married in 1956 and Shelton joined the U.S. Army. They moved to Fort Huachuca in Sierra Vista until 1958, when Shelton got out of the service. They had a son, Brad, and relocated to Bisbee, where Shelton taught English at the Lowell School until 1960.

Although Shelton and his family left Bisbee after a short time so he could enroll in an English PhD program at the UA in Tucson, he would later reflect on the old Southern Arizona mining town in his 1992 book, Going Back to Bisbee.

A sound recording of Richard Shelton, the late University of Arizona writing professor and poet, reading his poem "Whatever Became of Me" on Sept. 13, 1978.

“I read it before moving to Arizona, and it was an incredible orientation and story of this part of the world that gave me a profound sense of place,” said Tyler Meier, director of the poetry center, who moved to Tucson from the Midwest and formed a close relationship with Shelton.

“He was an incredibly supportive influence for me — around writing and the institutional life of the poetry center,” Meier said. “He was so proud of what the center had become and what it continues to evolve to adapt to and serve the art form.”

Poet, teacher, mentor

Writer and philanthropist Ruth Walgreen Stephan founded the UA’s poetry center in 1960, which houses one of the largest, most diverse collections of American poetry in the country, when Shelton was still in graduate school.

He never did earn his doctorate, though. As Houston remembers it, Shelton’s dissertation committee didn’t like his analysis of Elizabethan literature; instead of changing it, Shelton stopped his schooling with a master’s and was hired to teach writing in the English Department.

And that’s when he began making a reputation for himself as a poet, teacher and mentor.

In the 1970s, Shelton helped push for the establishment of the UA’s master of fine arts program in creative writing, which is now one of the top-ranked programs in the country.

His wife, Lois Shelton, became the longest-serving directors of the poetry center when she held the post in the 1970s and ’80s. Together, they hosted scores of nationally known 20th-century poets at their home, including Gary Snyder, Rita Dove and Joy Harjo.

All the while, Shelton kept writing and publishing, with his work appearing in some 200 magazines and literary journals, including The New Yorker, Poetry, Harper’s, The Atlantic and the Paris Review.

Notably, the late environmentalist Edward Abbey used a line from Shelton’s poem, “Requiem for Sonora,” (“oh my desert, yours is the death I cannot bear”) in the epigraph of his own novel, The Monkey Wrench Gang.

A view of the Richard Shelton Wall on the east side of the University of Arizona Poetry Center at the Helen S. Schaefer building. When light comes through the windows, it filters through poet Richard Shelton’s words, which are written in binary code cut-outs on a parallel stone wall.

“Lois and Richard worked hard to put the poetry center on the map, which put Tucson on the map as a place that cares about writers and poets,” Meier said. “They created a sense of identity for Tucson as a place that mattered in the national literary conversation.”

For his students, Shelton created a sense of belonging, but never at the expense of quality writing.

“He was a study in contrast. On the one hand, he was a super writing teacher who could bring out the best in people. But, he was also a very blunt critic,” recalled Erec Toso, a retired creative writing faculty member at the UA who was a graduate student when he met Shelton.

Toso was an older student with a young family at the time, and didn’t always feel like he belonged among the more traditional students in the program. But Shelton would always leave his office door open for any student who wanted to talk, and the two developed a close relationship over the years.

“I resonated with him because he was more of a ‘life’ guy,” Toso said. When it came to the craft, “He encouraged blurring boundaries,” and for Shelton, “talking about writing was talking about how to live.”

Legacy: Prison writing workshop

Shelton retired from teaching at the UA in the 2000s, but never stopped writing — or talking about writing.

Up until his death, Shelton had been working on a book of vignettes about his famous guests visiting him in Tucson. Getting Shelton’s last piece of writing posthumously published is now a goal of his close friend and protégé, Ken Lamberton.

“He always thought of himself as a teacher. If you were in his presence, you learned something from him,” said Lamberton, an accomplished writer and former student of Shelton’s, who considered him a father figure. “He gave me so much. Without him, I’d probably be living under a bridge.”

That’s not necessarily hyperbole on Lamberton’s part.

In 1989, Lamberton was incarcerated in Arizona’s state prison system with 11 more years left of his sentence, when he met Shelton, who had been running the Arizona Prison Writing Project since the ‘70s.

As Shelton recalled in his book, Crossing the Yard: Thirty Years as a Prison Volunteer, his idea for teaching prison writing workshops came after Charles Schmid — a convicted murderer known as the Pied Piper of Tucson — wrote to Shelton from lockup, asking for feedback on his poetry.

Over the next three decades Shelton spent nearly every Saturday hosting writing workshops for inmates, including Lamberton.

“Writing opened up a whole new world for me. The nature of incarceration is that your life is shrunken down to the size of a 4-foot by 10-foot-cell. Writing really opened up my eyes to seeing a world that was there and connected me to a larger community of writers,” he said. “(Richard Shelton) expanded my mind when I was in a dark place.”

Shelton helped Lamberton start publishing while he was still incarcerated, and when he got out in 2000, Shelton welcomed him into Tucson’s writing community. Lamberton continued studying with Shelton while working on his MFA in creative writing, and the two took several road trips together — even doing a joint book tour at one point — before Lamberton helped to care for his friend and mentor in the final days of his life.

Lamberton is now the director of the prison writing workshop Shelton founded almost 50 years ago. Keeping the program alive in Shelton’s absence is how Lamberton wants to honor the legacy of the man who gave him a chance 33 years ago.

“I want to keep working with those prisoners who have nothing, but have an inkling that maybe they could write poetry and show them how to do it,” Lamberton said. “It’s what I can do to pay him back and pay it forward.”