A paternity test is pending, but Bennu and Ryugu could turn out to be long-lost twins, separated at birth by a cosmic cataclysm.

New research by a University of Arizona-led team suggests the two near-Earth asteroids were actually sheared off and shaped by a single collision that shattered their original parent body roughly 1.4 billion years ago.

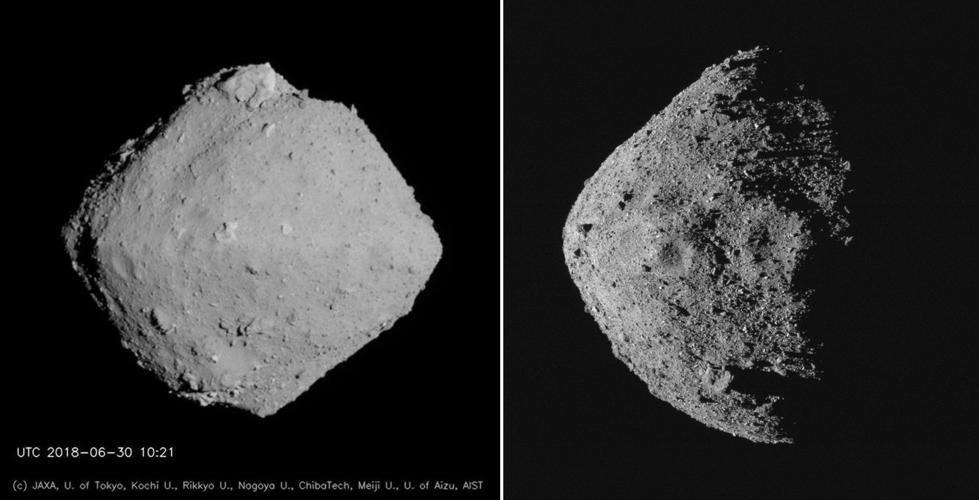

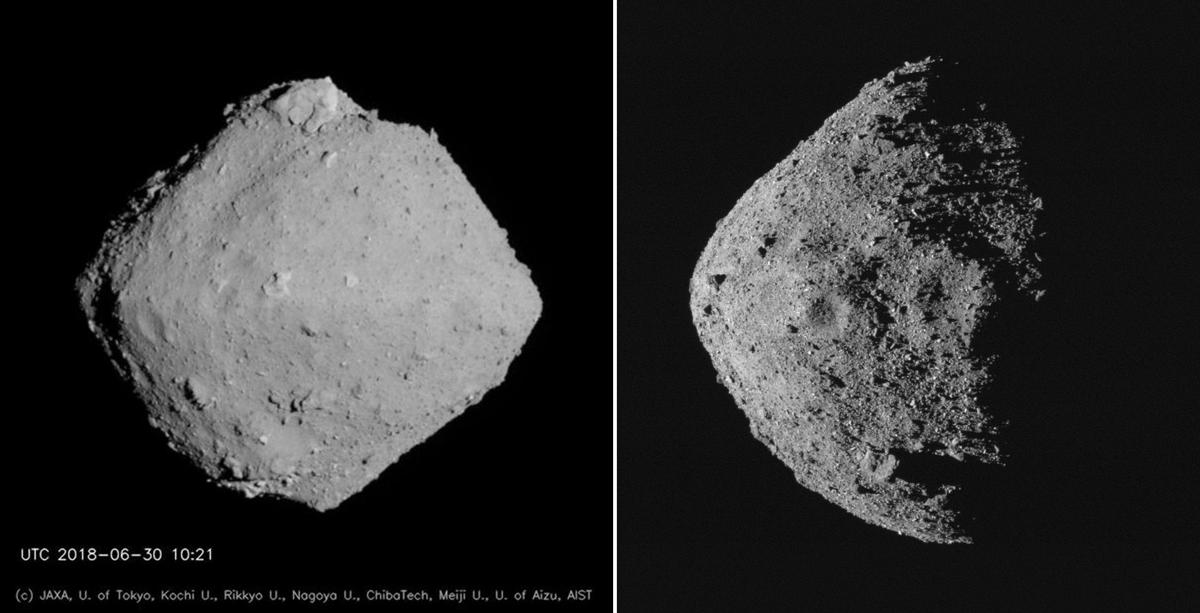

Since 2018, the so-called spinning-top asteroids have been under intense study by a pair of spacecraft, NASA’s OSIRIS-REx and Japan’s Hayabusa2. A new paper by the two research teams is challenging earlier ideas about how Bennu and Ryugu originally formed and how they got their top-like shapes.

Until now, scientists thought the pronounced ridges along the asteroids’ equators were formed by a gradual increase in their rate of spin, which caused loose material near the poles to migrate to the middle. But recent observations and analysis by the two mission teams indicate Bennu and Ryugu have been in their current shape since they were formed, as evidenced by old impact craters along their equators that otherwise should have been covered by migrating material by now.

“Using computer simulations that model the impact that broke up Bennu’s parent body, we show that these asteroids either formed directly as top-shapes, or achieved the shape early after their formation in the main asteroid belt,” said the study’s co-lead author, Ronald Ballouz, an OSIRIS-REx post-doctoral research associate at the UA. “The presence of the large equatorial craters on these asteroids, as seen in images returned by the spacecraft, rules out that the asteroids experienced a recent reshaping.”

The simulations could also help explain why the two asteroids contain different moisture levels, despite being created from the same parent object and the same collision.

Scientists suspect Bennu has a higher amount of water-rich clay because it is made out of material from the parent object’s surface or that was farther away from the impact that shattered it. By contrast, Ryugu contains less moisture because its material came from the parent’s core or closer to the impact site, which exposed it to more heat and evaporation.

NASA’s OSIRIS-REx, seen in this artist rendering, is set to collect samples from the asteroid Bennu Tuesday, Oct. 20.

The findings were published on May 27 in the journal Nature Communications.

Scientists expect to learn even more in the coming years, as samples collected from the asteroids return to Earth on board the two spacecraft.

The Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Hayabusa2 is currently making its way back to Earth. It is scheduled to arrive late this year with the rocks and dust it vacuumed up from Ryugu in 2019.

The university-led OSIRIS-REx mission is set to snatch its first tiny pieces of Bennu in October and return home with the material in September 2023.

“Once we have the returned samples of these two asteroids in the lab, we may be able to further confirm these models, possibly revealing the true relationship between the two asteroids,” said Dante Lauretta, the UA planetary sciences professor who is serving as principal investigator for OSIRIS-REx.

Scientists hope the collected minerals will also provide new insights into the origins, formation and evolution of other asteroids and meteorites — and of the solar system itself.

OSIRIS-REx was originally slated to collect samples from Bennu in August, but the operation was delayed until Oct. 20 amid disruptions caused by the ongoing coronavirus pandemic.

The mission team successfully rehearsed the delicate, touch-and-go sampling maneuver in April, and a second practice run is scheduled for Aug. 11.