Tucson grew up, or rather out, after World War II as the desert was carved into lots and filled with houses that, by and large, had the same basic design.

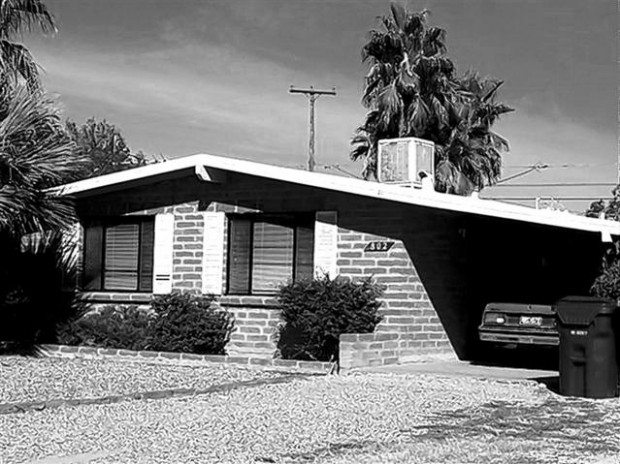

Pour a rectangular slab, sometimes deviating into an L or a U. Stack some block or brick for walls. Cover it and the attached carport with a low-slung roof built atop wooden beams or trusses.

Call it a "ranch" — a type of residential construction developed in California that swept across the country as a newly mobile middle class created American suburbia.

The ranch had big windows front and back, often with sliding-glass doors inviting an outside-living style. It had a rambling, adaptable interior.

In its many variations, the ranch seemed perfect for the desert lifestyle — especially in fall and spring when the warming sun heated its blocks and kept inhabitants cozy through the mild nights.

In winter and summer, with little insulation, it was another story, but, hey, energy was cheap. Just crank up the furnace or that new-fangled central air conditioner.

Those were the days when gas stations had price wars, and you could cruise Speedway all night with the pocket change you lifted from your father's dresser caddy.

That all changed in the '70s. The energy crisis put a premium on the well-insulated home. Land costs dictated smaller lots and more compact housing footprints. The single carport gave way to the two-car garage. The era of the ranch house passed.

Part of history

Now those ranch-house subdivisions are reaching the age at which we call them historic, and some are perplexed by that.

Are these nondescript homes really worthy of preservation?

"Each generation that lived in that era of the creation of a type feels the same way," said architectural historian R. Brooks Jeffery.

People who left their Downtown Sonoran rowhouse and their Armory Park bungalows, for roomier ranches on the East Side and the Foothills, never dreamed they were deserting architectural masterpieces, Jeffery said.

It may take some time for most to appreciate the ranch house, which Jeffery said represents an entire value system — social, political, economic and aesthetic — that came into play during the biggest blossoming of American development.

The baby boom that followed World War II gave a demographic push. Economic good times created a middle class and a larger market for home ownership. The blossoming car culture made suburbs possible. The U.S. government promoted mortgages through the Federal Housing Administration.

The ranch house wasn't simply a type of architecture. It was the emblem of a changing way of life.

"We may look and say it's not the most beautiful architecture, but it's certainly the most significant," Jeffery said.

"It is one of the most important periods of American history," said Debbie Abele, who conducted a study of Tucson's post-war development for the city's Department of Urban Planning and Design.

"What people call banal or nondescript was a standardizing of building parts that made home ownership available to a larger percentage of the population than ever before," said Abele, a consultant who also serves as the city of Scottsdale's historic preservation officer.

Tucson should celebrate the fact that many of its ranch homes have a unique style that celebrates the place where they were built, she said.

Abele characterizes 11 styles of postwar housing (1945-73) in her report, with seven styles of ranch, including the Tucson Ranch, with its adobe blocks and low roofline, and the Spanish Colonial ranch, with its tiled roof.

Most are small by today's standards — an average of 1,600 square feet on a 9,400-square-foot lot.

Most Tucson ranch houses were not part of large subdivisions, said Jonathan Mabry, Tucson's historic preservation officer.

They were built two to three at a time by small builders, though some of the most striking and recognizable examples of the form were production homes.

Historic districts

Winterhaven, that greenly landscaped enclave of brick ranch houses north of Fort Lowell Road, between Tucson Boulevard and Country Club Road, is one. It is currently the only one of 21 Tucson neighborhoods registered as National Historic Districts that was totally built after World War II, Mabry said.

It won't be the last.

The city commissioned a study of postwar housing partly because it expects "a tidal wave of applications" for historic designation as neighborhoods reach the 50-year cutoff for historic status, Mabry said.

It can be an expensive process — hiring an architectural consultant to determine whether 51 percent of an area's homes would be "contributing properties."

The payoff comes in property-tax reductions of 40 percent to 50 percent for homeowners who promise to retain the historical look of the home from streetside.

Mabry said the city wants to target lower-income areas that can't afford the studies themselves, helping them get grants and providing matching funds if needed.

Not all 50-year-old neighborhoods are worthy of preservation, he conceded. The city wants to identify those that meet at least two of the federal criteria for historic status.

One neighborhood just outside the city limits should be a slam-dunk, Jeffery said.

Indian Ridge, northwest of Tanque Verde and Sabino Canyon roads, was built by Robert Lusk, who designed several variations of what he called the PAT, or "Perfect Arizona Type."

His homes are characterized by adobe block walls and deep gabled roofs with windows between the tops of the walls and the roofline.

Like many ranch houses, the perfect home is tough to heat and cool, said Clague Van Slyke, who bought his new Indian Ridge home in 1960. "My heating bill from last month tells me that," he said.

The hipster ranch

Mabry said the ranch house can be adapted to more energy-conscious times with additional roof insulation and meticulous weather-proofing of door and window openings.

Those who argue that the houses shouldn't be preserved in the name of sustainability miss an important point, he said.

Many of these homes are well-built, with another 50 or more years of life left in them, he said. Replacing them with a more energy-efficient model ignores the environmental cost of building a new house.

In Phoenix, where most ranch houses are block rather than brick, the preservation and adaptation of ranch homes has become a movement of sorts, Abele said.

There is a premium placed on "midcentury modern" houses by such recognized architects as Charles Schreiber and Ralph Haver, and the lowly ranch has become a palette for updated interiors in spare modern style.

Alison and Matthew King, both trained as designers, live in a Haver-built ranch house in central Phoenix.

"I think its big appeal is that marriage of indoor and outdoor living. You take it for granted today, but homes prior to this era were not built that way," said Alison King.

"We love the openness of space and light and the flow. I think there is an orderliness about it — very organized yet casual living."

King started a Web site, www.modernphoenix.net, that celebrates the midcentury modern home, and yes, the ranch is one of those midcentury modern forms.

In Tucson, the Modern Architecture Preservation Project, which mostly works on saving larger buildings, has begun a list of midcentury neighborhoods on its Web Site (www.mapptucson.org).

King said she's beginning to get Tucson participation on her Phoenix-based site.

They're spreading the word. Modern is historic. The ranch is hip.

take the quiz!

Test your knowledge of Tucson ranch-house styles. B2