The University of Arizona Mobile Health Program, which provides free health-care services to those without insurance or limited access to insurance, has expanded its service and hopes to grow even more in the coming months.

The program, run by the UA Department of Family and Community Medicine, recently began providing health-care services to the Amity Foundation Circle Tree Ranch, a nearly 50-year-old therapeutic community for alcohol- and drug-addiction treatment, and the nearby transitional housing project, Dragonfly Village.

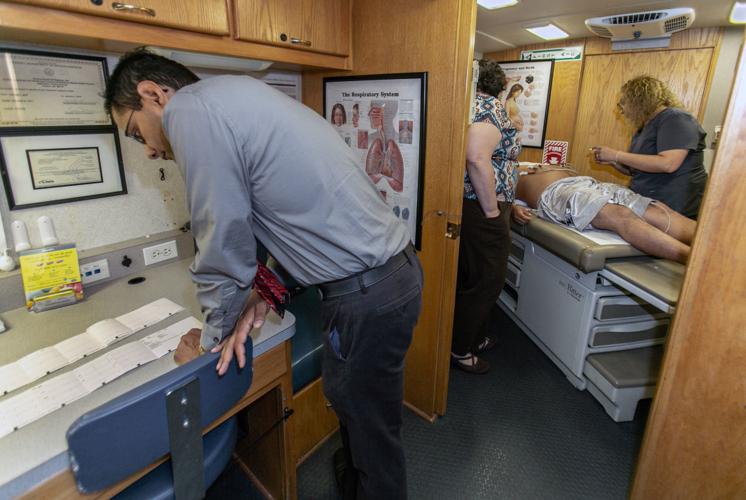

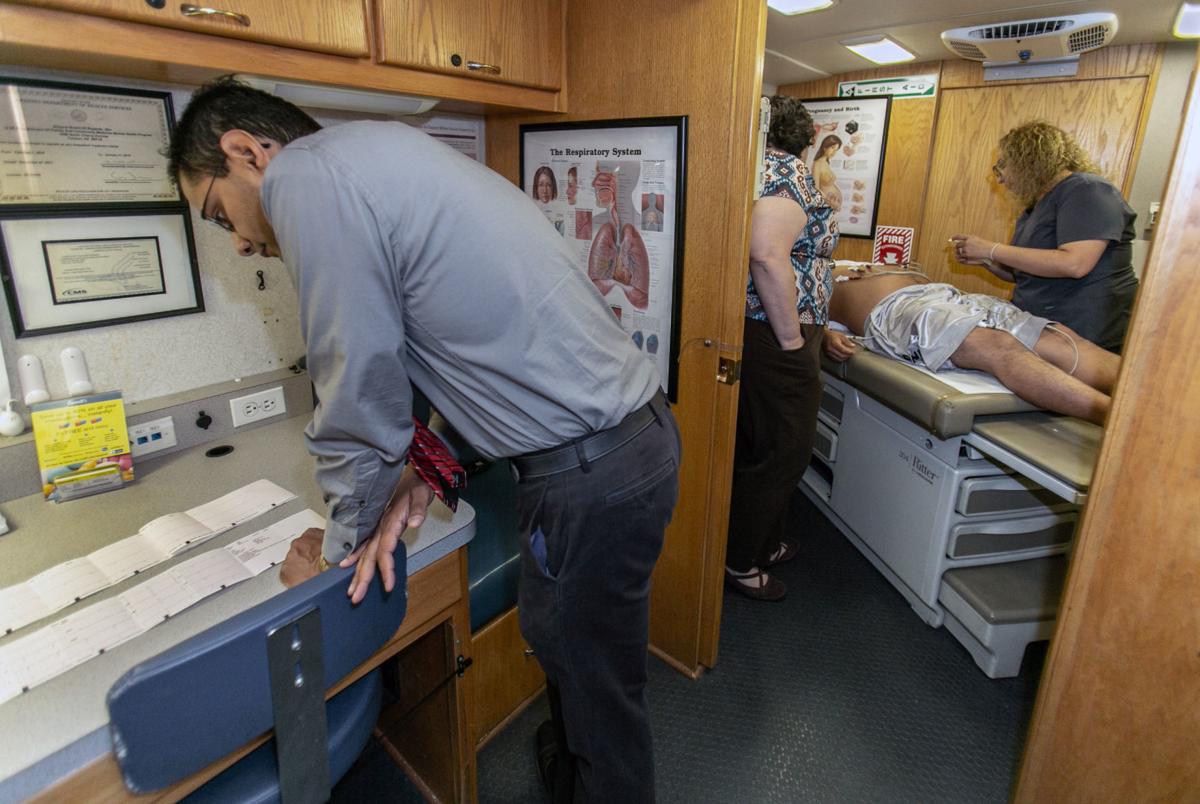

UA Mobile Health is a primary-care practice on wheels, traveling between sites on a regular monthly schedule to provide acute and chronic care for patients of all ages. The Mobile Health team also provides low-risk pregnancy care and limited dental screening. Preventative care, including Pap smears and sports physicals, is also provided.

The clinic typically rolls up to schools and community centers to provide its services. The program operates on a little more than $400,000 a year and serves 1,800 patients annually.

Support comes from the UA, Banner-University Medical Center and Pima County. Donations and grants also come from the March of Dimes Foundation, the Delta Dental of Arizona Foundation, Sonora Quest Laboratories and the Arizona Diamondbacks. The clinic also receives an endowment from Dr. Augusto and Martha Ortiz, who founded the program more than 40 years ago.

Dr. Ravi Grivois-Shah, the medical director for UA Mobile Health, would like to expand further. The clinic visits sites once every two weeks. But Grivois-Shah someday hopes to be at every site at the same time every week.

“It helps cement in patients’ minds, ‘I need some help and I know where to go,’” he said.

Medical assistant Edna Rodriguez escorts Vincent Ascencio to the UA Mobile Health Program bus at the Amity Foundation’s Circle Tree Ranch.

He also envisions visiting rural sites four times a year and providing telehealth services between visits.

Many patients, about 30 percent, would have gone to the emergency room had UA Mobile Health not been a resource, according to a recent survey of patients using the program. The rest would have gone without care.

But emergency rooms can mean long waits and expensive copays, even for someone with insurance. For those without, it could mean debt or bankruptcy.

“A lot of Mobile Health clients are also working poor, who have low premiums but high deductibles. Others are in the doughnut hole who don’t qualify for Medicaid, but subsidies are not enough to cover the cost of private insurance,” Grivois-Shah said.

“It’s a good way to reach a community that otherwise wouldn’t have care.”

The mobile clinic is also available for people with other barriers to care such as immigration status or lack of transportation. For example, the health clinic visits high schools and is available for students during homeroom periods.

UA Mobile Health “really does fill in the gaps of care,” Grivois-Shah said. “Community health centers also serve that purpose, and our colleagues at El Rio or Marana Health Care or Mariposa (Community Health Center) really help us meet those gaps, but even community centers have barriers like cost-sharing and wait lists.”

Despite concerns about a heart problem, Vincent Ascencio, with medical assistant Edna Rodriguez, was found to have swollen cartilage.

Better access to health care

Vincent Ascencio was playing basketball on the evening of Aug. 20 when he felt pain in his chest.

“I was scared,” said. Ascencio, a 29-year-old student at Circle Tree Ranch.

Clients at the ranch are referred to as students because, “We don’t want the connotation of ‘the patient,’” said Beth Anne Laos, an advanced-practice registered nurse who serves as wellness director and provides community relations for the ranch. “We do it so it gives them a sense of self-esteem and worth.”

After a campus nurse checked Ascencio’s vitals, she determined it was not a heart issue. Ascencio could go to the hospital immediately or wait for the mobile clinic.

He decided to wait, and Laos signed him up for the first time slot the following morning.

The new partnership, with regular visits to the Circle Tree Ranch and Dragonfly Village, will provide those populations with better access to care. Many are uninsured, or have limited access to insurance or transportation.

Circle Tree Ranch students also won’t have to disrupt curriculum with hours-long, supervised trips off campus.

Ascencio spent about an hour in the clinic, which is longer than most patients, but it beat the alternative:

“Last time I went to do blood work (off campus), it was a walk-in. I stayed for three hours,” he said. “It didn’t disrupt my curriculum, but it could have on other days.”

Ascencio was uninsured when he was injured in a car crash. He drank heavily to ease the physical pain; eventually it morphed into an addiction.

At the ranch, UA Mobile Health will not focus on addiction or mental-health issues. That’s the ranch’s mission.

Instead, the clinic will serve as a convenient resource for acute and primary care.

“Our sites are most successful when we have really good buy-in from the partners on the site who can identify the clients and students or family members who really need the services,” Grivois-Shah said.

Ascencio left the clinic feeling less worried. The pain was not from his heart, but originated from swelling of cartilage between the ribs. He returned to his day, greeting other students around the ranch.