UA assistant professor Mónica Ramírez-Andreotta has been heading up citizen science programs for years in an effort to be a steward of the environment and to help underserved communities.

With a $2.3 million grant from the National Science Foundation, Ramírez created Project Harvest, a five-year citizen science program in partnership with the nonprofit Sonora Environmental Research Institute Inc. She and her University of Arizona team train community leaders, called promotoras, to guide citizen scientists in urban and rural towns in testing for neighboring sources of industrial waste pollutants in rainwater runoff from roofs, soil and plants.

While families in mining communities might not necessarily be anti-mining and many work for the mines, Ramírez said, many have concerns about what pollutants might be in their immediate environment and in harvested rainwater for gardens.

The program is underway in communities such as the mining and industrial towns of Hayden-Winkelman, Globe-Miami and Dewey-Humboldt, and also on Tucson’s south side, reaching about 160 households.

“Why do minority and/or low income people live closer to waste than others?” Ramirez said. “When you see environmental injustices, you are reminded why you went to school in the first place — it’s to create change.”

Samples of rainwater collected by citizens in California and Arizona are shown in a refrigerator at Saguaro Hall on July 19, 2018. The water is collected to test the health of the harvested rainwater.

A budding passion

Ramírez graduated from Tucson High School in 1997 then went on to the UA to earn dual bachelor’s degrees in photography and ecology and evolutionary biology.

She realized her passion for the environment stemmed from formative experiences.

She saw the impact that changes in ecosystem resources had on family members in Mexico. They relied on a nearby river for running water and for fishing, so when the water level dropped one year, she saw they had to adapt to new sources for food and income.

Ramírez also remembers her frustration when former President George W. Bush backed out in 2001 of the Kyoto Protocol, an international treaty that set emission reduction targets. She felt compelled to act.

“I was like, what do I need? I have an art degree, so I know how to communicate, I have a science degree, now I need the policy so I can infiltrate and change things,” Ramírez said.

She earned a master’s degree in public administration with an emphasis in environmental science and policy at Columbia University.

Her first job out of school was as senior instructional specialist and community outreach coordinator for the UA’s Flandrau Science Center and Planetarium. There, she realized that she couldn’t be the leader of her own research without a Ph.D.

She earned the title of Dr. Ramírez in 2012 from the UA.

As part of her dissertation, Ramírez created Gardenroots, in which she trained community members living near legacy mines to test for environmental pollution and share that knowledge with the communities and stakeholders.

She even led an urban version of Gardenroots in Boston while working as an assistant professor at Northeastern University.

Ramírez returned to the UA in 2015, realizing that many community members are concerned about environmental quality.

Gardenroots participants as well as other gardeners throughout the state wondered about the quality of harvested rainwater. After teaming up with other researchers in her department, Project Harvest was born.

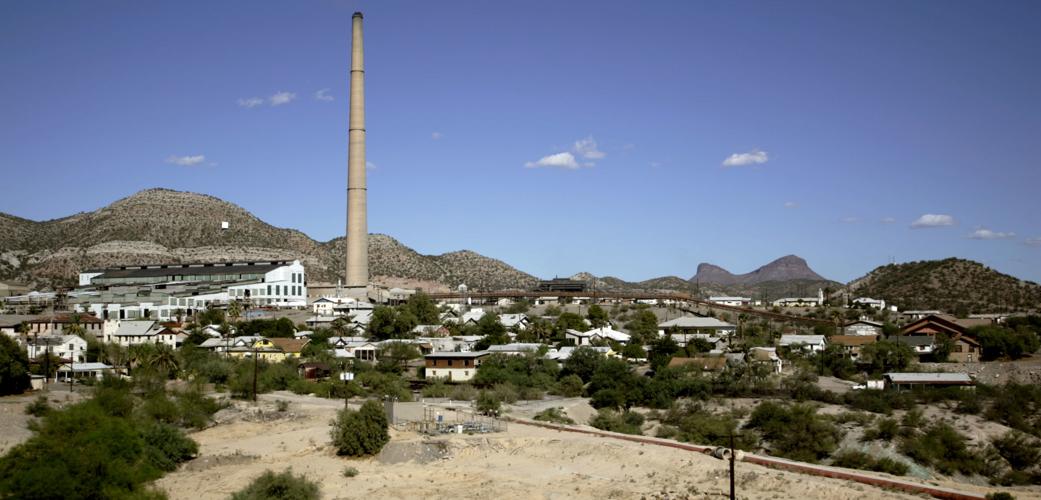

The town of Hayden, where mining is a mainstay, and the ASCARCO smelter in 1982.

Project Harvest

As a kid, Lisa Ochoa played in the tailings of the Asarco Hayden smelter site in the small towns of Hayden and Winkelman, about 70 miles north of Tucson. She remembers a friend using the colored waste runoff as play makeup.

“We just didn’t think about it,” she said.

Strong winds would kick up clouds of fine, white dust from the mine tailings. The mine has since kept such tailings watered down.

When Ramírez rolled into Hayden-Winkelman to host a school family science night and pitch Project Harvest in 2017, Ochoa offered to be a promotora to channel her curiosity about the health and environmental consequences of the mine’s waste.

Ochoa believes she is free of health issues attributed to mine pollution, but she wonders if some of the cancers and other illnesses around town might be related.

“In Hayden and Winkelman, Arizona, there are high levels of lead and arsenic in the air, mine waste piles and soil in some nonresidential locations,” according to the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry.

Lead exposure can cause learning and behavior problems in children, according to the agency. Arsenic exposure can cause skin problems, stomachaches and nausea. Long-term exposure increases the risk of cancer of the skin, bladder, lung and liver.

A 2015 investigation by the agency found that the children in Hayden and Winkelman have higher-than-national-average amounts of lead in their system. The study was conducted during a period when the mine was closed for maintenance. A follow-up investigation is underway to retest arsenic to obtain more realistic results.

Additionally, the investigation could not conclude if the increased levels of lead originated from the mine or from outdated pipes, paint and other environmental factors.

Asarco officials could not be reached for comment.

Asarco upgraded the Hayden smelter to meet U.S. air-pollution rules as part of a 2015 settlement with the EPA.

Ochoa has worked for the Hayden-Winkelman School District for 25 years as a science and math teacher.

As a promotora, Ochoa mentors those in her community on the procedures the citizen scientists must follow for Project Harvest.

With English and Spanish pamphlets and videos, Ramírez and her team outline the process of collecting water, plant and soil samples around a participant’s house. Half of the participants send the samples to a UA lab in Tucson, while the other half test them independently, then send in their data. Ochoa acts a a liaison between her community and the UA researchers.

The citizen scientists are checking for a suite of possible pollutants, including microorganisms and organic compounds, in addition to arsenic and heavy metals.

“As a scientist, my job is to produce evidence-based information,” Ramírez said.

In addition to quantifying the levels of these possible pollutants, she wants to know what participants gain from the experience of the scientific process.

Additionally, she will flex her artistic know-how with the promotoras and UA research and design team to produce both traditional data as well as nontraditional art exhibitions. Ultimately, the goal is to share the results to inform environmental decision-making.

Becoming more

than a “Yola”

Ramírez realizes she has a duty to do this work because of her position as a professor at a land-grant research university.

While working on her Ph.D., one of her main advisers, professor Mark Brusseau, called Ramírez into his office. He recognized her passion and encouraged her to become a professor.

Ramírez was skeptical — she didn’t see that in herself.

“You need mentors and people to believe in you and tell you you can do it,” she said. “I think believing in someone is one of the most important things to give back.”

But not everyone saw in her what Brusseau, a UA professor of soil, water and environmental science, did.

At conferences and community meetings as a Ph.D. student, “People would be like thanks, young lady, you can go sit down now, but they would never say Ms. Ramírez, or Dr. Ramírez, Mónica or anything,” she said.

Her mentor balked at the treatment he witnessed and dubbed her “Yola,” for young lady, as a joke.

Despite being treated differently than her peers, she persisted. “The job of a professor is to teach the next generation and be a service to the community and that’s a big responsibility that I take very seriously,” she said.

“She’s a good teacher,” Ochoa said. “It’s her passion. It’s like you can see it. ... It makes you want to get involved.”