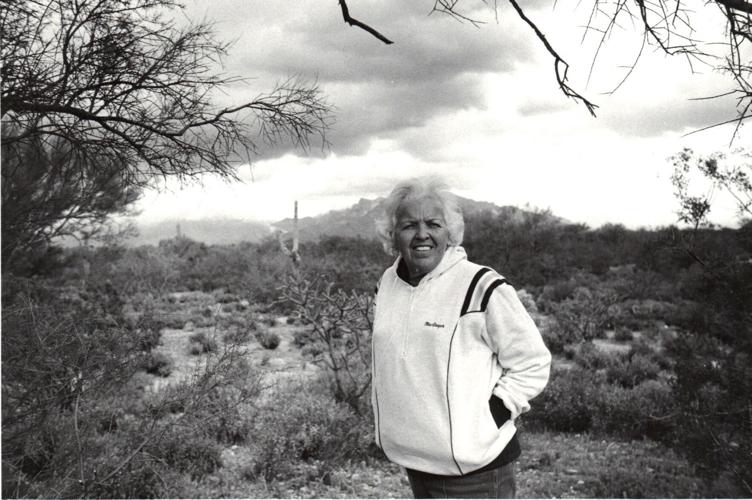

In the 1960s, a sign near the intersection of Thornydale and Overton Roads announced the location of Rancho Estrellita (Ranch of the Little Star), a 40-acre spread that was home to a menagerie of injured and orphaned birds and animals.

Sarah Gorby did not own the property but lived there for over 20 years caring for the creatures that were brought to her to nurse back to health, shelter and rehabilitate before returning them to the wild. She was the first wildlife rehabilitator recognized by the Arizona Game and Fish Department.

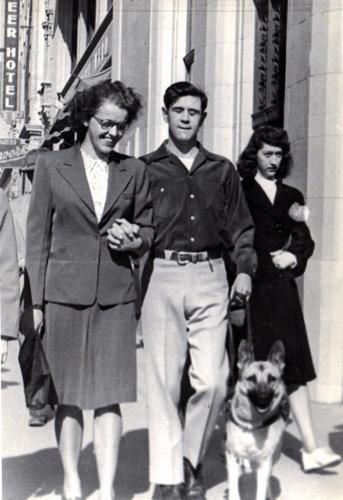

Sarah Ann Pearce was born May 7, 1916, on a farm near Huntingdon in southern Pennsylvania. At age 17, to escape an abusive father, she left home, landed in Cleveland, Ohio, and obtained a job as a crane operator (one of the few women to hold the position), and later drove military vehicles in convoys across the country for shipment overseas during World War II.

Somewhere along the way, she met Dan Gorby, an Army veteran who had lost his eyesight during the war. The couple married in Tucson on Dec. 19, 1947.

For a few years, Sarah worked as a real estate agent until Dan’s health required her full-time attention. Their daughter, RaMar, born in 1953, also added to Sarah’s responsibilities.

By the mid-1960s, the family was living at Rancho Estrellita, and Sarah was caring for injured and orphaned animals. Word spread that Sarah would accept just about any creature in need of help. She welcomed javelinas, skunks, raccoons, deer, bobcats, coyotes and tortoises, plus hundreds of birds into her home and onto her furniture. Over the years, she even entertained an alligator and a couple of motherless polar bears.

Orphaned fawns slept in her fireplace while a Gambel’s quail hunkered under a priceless Indian blanket. At one time, five owls took over one of the rooms in her house and baby javelinas were housed in her bedroom so she could haul them into her bed every couple of hours for feeding.

According to Sarah, “I have the only javelina in the country that sleeps on a waterbed and pees on the Wall Street Journal.”

March 8 marks International Women's Day. Here are 25+ stories of Arizona women who made their mark in the early history of the territory and t…

Yet Sarah did not attach herself to the animals she cared for. “They are not pets,” she admonished. “I know when I get 'em, they’ve got to go.” Her goal was to return as many as possible to their natural habitats.

Dan died in 1975 and by then, word had reached the Arizona Game and Fish Department that a woman was keeping wild animals in her house and on her property, an illegal activity. An agent appeared on Sarah’s doorstep to investigate but once he saw the care Sarah gave the animals, he not only refused to reprimand her but declared, “you don’t need to be cited, you need to be licensed.” In November 1975, she was officially certified by Arizona Game and Fish to care for wildlife.

The agency brought her animals to nurse back to health, orphaned javelinas, bobcats and coyote cubs whose mothers had been killed, and large birds of prey with injured wings or broken beaks. Not all could be saved, and if they could not be rehabilitated, they either stayed with her or were turned over to zoos or animal preserves.

Local veterans donated their services and made house calls to Sarah’s place. Game and Fish gave her guidance when needed but had little money to provide for the animals’ care and feeding.

Every day Sarah rose before dawn, fed the baby animals before heading out to pick up donated day-old fruits and vegetables from local grocers. Butchers provided meat scraps, bakeries gave her stale bread. She also harvested fresh roadkill, a necessary food source for some of the animals.

Friends and neighbors dropped off unwanted and injured animals, and she acquired a collection of supporters who donated food, hay, lumber and labor.

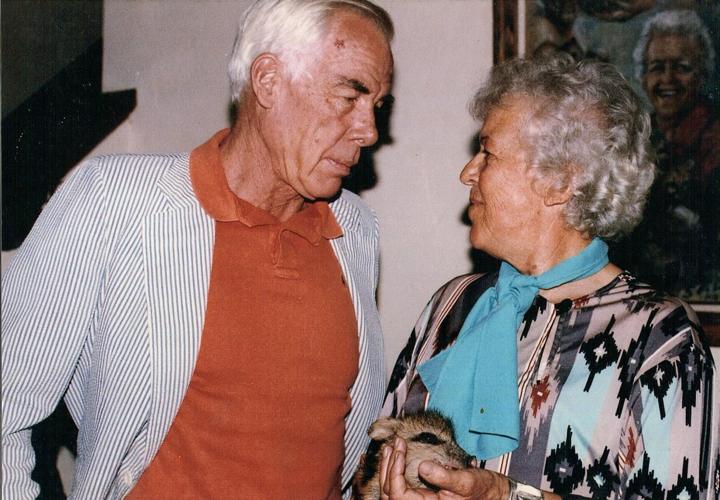

One of her most famous advocates was actor Lee Marvin, who was living in Tucson at the time. After the two became friends, Marvin was often seen around Sarah’s place picking up trash and hauling it to the dump. She once remarked to him that she “certainly got a better class of garbage man these days,” and Marvin supposedly reported that Sarah’s house was the only one where he had to wipe his feet on the way out instead of on the way in.

Since Game and Fish had few resources to help Sarah financially, Marvin started hosting fundraisers in 1982 to help Sarah care for the animals. Through the years, the event was held in locations such as the Tucson Racquet Club, Tohono Chul Park and Tanque Verde Ranch, where Sarah often gave presentations educating the public on wildlife. This annual affair continued until 1990, even though Marvin died in 1987.

In 1983, Rancho Estrellita was sold although Sarah was allowed to remain in her home until 1986. She moved down the road a short distance near Ina and Thornydale Roads to a converted barn she dubbed “Der Stable,” and continued her career as a wildlife rehabilitator.

In April 1990, Sarah announced her retirement from wildlife rehabilitation. Two weeks later, she died. Around 200 people attended a memorial service for her that was held at Catalina State Park. Her ashes were strewn over Mount Lemmon.