This is the thing about public schools. They exist to educate kids. But that’s tilting at windmills if other basic problems — food, shelter, clothing, safety — aren’t addressed.

Say all you’d like that schools can’t fix everything, how people shouldn’t have kids they cannot care for or even want, how parents should stop taking drugs, etc., etc., etc.

None of that changes this simple fact:

The children are here.

They exist.

And they need help.

Condemning parents’ shortcomings, or their outright failings, doesn’t feed a child or make sure that he has a warm coat or that she has a pencil to do her homework.

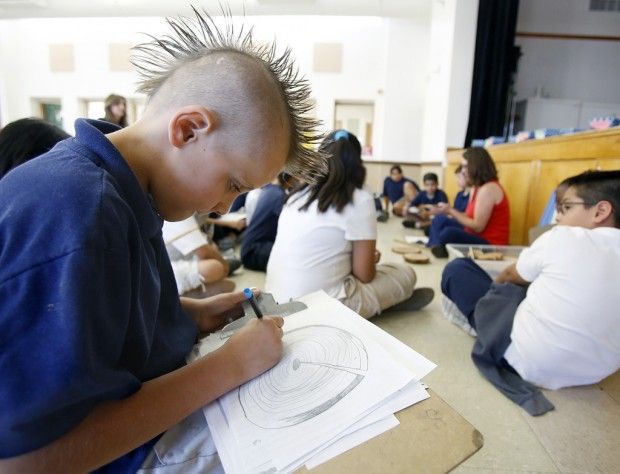

Children, like many of the students at Walter Douglas Elementary School and at others across Tucson, bear the brunt of poverty.

Adults, at least in theory, can do better for themselves.

But children cannot do it alone.

At Walter Douglas, they don’t.

ONE GOOD MEAL A DAY

Lunch happens five times a day over two hours at Walter Douglas, which is on North Flowing Wells Road a few blocks north of Miracle Mile. More than 91 percent of the kids qualify for federal free or reduced-price lunch — the highest percentage in all Flowing Wells schools as of March.

In 20 percent of public district schools across the Tucson area at least nine out of 10 students have family incomes low enough to qualify for the federal lunch program.

At 67 percent of district schools more than half of the kids qualify.

Walter Douglas students file in to the cafeteria by grade level.

The kids move through the line, choosing white or chocolate milk. Pizza or a chicken sandwich. Sliced carrots, beans. For a lot of kids it’s their biggest — and most consistent — meal of the day.

In the cafeteria, ranch dressing is gold. It goes on everything: salad, burritos, pizza.

Staff members control the squirt bottles — they learned quickly that a kid’s version of “enough” ranch verges on the oceanic.

“Don’t you want some fresh veggies?” asks Assistant Principal Crystle Gallegos as we make our way to the cash register. She nods toward the salad bar.

I glance around for the student who is the target of her question, making a mental note about how everyone pushes the importance of veggies.

Gallegos looks at my plate and arches an eyebrow at the solitary slice of pepperoni pizza on a whole wheat crust.

She is talking to me.

I gather some baby carrots and cucumber slices.

And it hits me:

Prosperity is the privilege of making unconscious choices — I can afford to pass up vegetables at lunch because I can have them at dinner. What a luxury.

Encouraging families

Walter Douglas Elementary opened 50 years ago. The campus will celebrate its golden anniversary with a community party in October. They’ve been raising money and saving for it.

The Parent Teacher Organization gives every teacher $100 to help cover extras each year. They use it for field trips or to buy classroom supplies. PTO President John Musselman says his goal is to increase the stipend.

“In my dream world it would be $125 for each teacher, but that is huge within our budget,” he says.

Teachers agreed during a May PTO meeting that an extra $25 would be great, but they suggested the money be used for the October anniversary celebration first. Then the group can revisit the issue.

Everybody at Walter Douglas, and in the Flowing Wells district, knows that many of their families have it rough. It’s a fact acknowledged in the donated snacks provided to students, in the boxes of shoes, socks, pants and shirts stacked on a high shelf in the nurse’s office, in the free books given to kids who attend the monthly Read and Eat nights.

Attendance at the school’s many academic activity nights, like Read and Eat, went up when the school began providing a free meal. That happened after teachers talked to families about what their kids were learning in class, and how they could help at home.

On a warm March evening several teachers speak over the din of a cooler and pause for a translation into Spanish.

The moms, dads, grandparents, aunts, uncles, cousins, siblings and family friends come to support their kids’ education, but the incentive of pizza and punch doesn’t hurt.

Families sit at cafeteria tables, reading with their children. Your kids need to see you read at home, so they know it’s a skill your family values, the teachers say. It doesn’t matter if you’re doing it in Spanish or English: Just read with your kids. Build that expectation.

The message gets through. A small girl in pink sits at the end of a long table and reads “The Grinch Who Stole Christmas” to her younger brother.

“I’m reading to him so he can learn,” she explains. Her brown ponytail swings, she grins and exudes big sister authority.

Calculus of opportunity

Walter Douglas isn’t working in isolation.

Elks Lodge 385 sponsors a shopping trip for 25 kids who need assistance. The lodge also helps kids at Homer Davis and Nash elementary schools.

Teachers suggest names of students for the excursion, and Principal Tamára McAllister and Assistant Principal Gallegos make the final list. Far more kids need the help than there are spots.

Once the list is winnowed — who has been before, who may receive help from another source — practical questions must be considered.

The shopping trip happens on a Saturday, which means someone must bring the child to Walter Douglas around 8 a.m. and come back around 2 p.m.

One boy in particular needs clothes, but staff know his parent frequently is late — sometimes by hours — for pick-up after school. Calls home go unanswered.

When no one comes for a child, after all other options are exhausted, McAllister or Gallegos have to call the police.

So McAllister and Gallegos must decide: Do they give this slot to the boy who desperately needs it but whose parent likely won’t come through? Or do they award the spot to another child?

McAllister and Gallegos have no choice, really. Giving the spot to the first child would likely mean letting it go unused — it’s too precious.

Another student is selected.

The calculus of opportunity is cruel.

Shopping for basics

The morning of the shopping trip the kids gather at the school and board a yellow bus with some of their teachers, Gallegos and McAllister. They ride about 20 minutes across town, to the entrance of JC Penney at El Con Mall. Clustered at the door are a group of grown-ups — the waiting Elks.

The young shoppers have the run of the store. It hasn’t opened to the public yet, but JC Penney’s staff are on hand to find the right sizes, to try to explain the unanswerable of why women’s underwear and clothing don’t follow the same sizing system and, finally, to ring everything up.

Kids are paired with Elks, and they rove the store looking for items on their checklist: shoes, jeans, shirts, underwear, socks.

What are slacks?

The Elks Lodge raises money to spend $100 on each child, and Penney’s gives them a discount.

“Let’s go upstairs and get some slacks,” says one Elk, a business owner, to the two girls he is helping. He holds a box of pink sparkly shoes that the fourth-grader has deemed “perfect.”

Pause. Head tilt.

“What are slacks?” Not an unreasonable question from an 8-year-old raised in the Tucson heat.

“Pants.”

“OHHH!” Giggle. Nod. They head up the escalator.

Upstairs, in the shoe department, a clerk measures the feet of a tall fourth-grader. She points to the rows of men’s athletic shoes.

There’s a problem. All of these shoes have laces.

The Elk asks the clerk if they have any shoes with Velcro, like the child has always had. The boy’s own shoes are dirty and worn, obviously too small. He’s had them for a long while.

Gallegos sees the brewing anxiety and heads over. She assures the boy that he can learn to tie his shoes. They’ll help him, she says.

I see him in class a couple weeks after the shopping trip. One day he’s wearing the old shoes. But the next, it’s the new ones. There’s no way to make sure the gifts stay with the kids — sometimes someone else in the house needs them more.

In Penney’s many of the younger kids are floating. A boy runs back and forth in the shoe department, thrilled beyond belief at his new shoes. They fit. And they feel so good.

“LOOK HOW FAST I AM!”

All the adults smile and cheer him on, but it’s bittersweet.

Bittersweet because he is fast. And because, for that moment, he is unstoppable.

But we all know that this boy has a steep road ahead. His family isn’t stable, and he doesn’t always get medications he needs. He’s a wonderful boy, sweet and curious.

I see him in class later and he struggles — but he is excited to learn. He tells me all about caterpillars.

Nothing in this child’s life is going to be easy.

Surprises from elks

Some of the older kids know what’s up, why they have been chosen for this excursion. They’re having fun, and are appreciative, but their faces are tinged with too much knowingness.

They realize they are here, selected for this fantastical day, because they are poor.

The herd of Elks and kids move out of the store, giant shopping bags in tow. Students board the bus, Elks get in their cars and they all reunite at the Elks Lodge on Oracle Road.

After a lunch of kid favorites — tater tots, chicken nuggets, coleslaw, cookies — a parade of gifts begins. Basketballs, backpacks with their names sewn on, art supplies, candy, a dictionary, pencils, fruit.

And finally, a new bike — for each of them. There is no happier sound than a child’s joy.

I stand with a girl in line to get fitted for her bike helmet.

“I asked Santa for a helmet for Christmas, but he didn’t bring one,” she says. “He was just late.”

In all, the Elks spend about $5,000 per shopping trip.

Back at school parents struggle to stuff the gifts in their cars. They didn’t know they were going to have bikes to get home. But this is a good kind of problem to have.

And, despite McAllister and Gallegos’ specific instructions to pick up their kids at 2 p.m., some parents still don’t show up for several hours.

Most of all, I am proud

On May 23 Walter Douglas Elementary had what was most likely the best last day of school in the history of last days of school — ever.

A lot of what kids at Walter Douglas deal with is gut-wrenching. It’s hardship that no child should have to experience.

But at its heart, at its root, Walter Douglas exists to educate. To prepare kids as best a school can for their future, whatever that holds.

The school embraces a positive approach to student behavior. Everyone is on the lookout for kids doing good things — helping another student, working hard, acting respectfully — and those moments are recognized.

This year the kids have quarterly schoolwide goals. They must go specific numbers of days without a student receiving a referral to the office for negative behavior.

In a school of almost 700 kids, that’s a tall order. But they do it.

They must work together to achieve them — and they share the rewards.

And what rewards they are.

During the third quarter they duct-taped Gallegos, the assistant principal, to the gym wall.

The final challenge is to have eight days with no one sent to the office for negative behavior.

It’s close, but they make it.

So on the last day of school Principal McAllister puts a rain poncho over her clothes, tucks her hair into a shower cap and dons sunglasses. She climbs into an inflatable pool in front of the entire school in the gym.

Grade by grade the students line up, gather their supplies and go to work.

They are turning their principal into a human banana split. They cover her with ice cream, chocolate sauce, nuts, whipped cream, sprinkles.

And it is magical. Kids sing, McAllister dances, Gallegos announces the toppings and everyone claps.

“I am very cold, I am very sticky, I am delicious,” McAllister tells the students. “But most of all, I am proud of my Walter Douglas Bulldogs!”

Supreme, unfettered joy.

Glorious.

And then they’re gone

Afterward McAllister shuffles off, scooting across the floor on a trash bag to avoid leaving a gooey trail, to a gym shower.

A group of sixth-grade boys helps with the cleanup. They fish the bananas out of the melted ice cream in the pool — they’d get stuck in the wet-vac.

McAllister reappears a short time later, a few errant sprinkles in her hair. Back to work.

At the end of the day McAllister puts the song “Who Let the Dogs Out” on the campus intercom. She and Gallegos stand together where the kids line up for the bus.

Students pass by, some in tears, and come over for hugs.

“Even if you’re at a different school, we still want to know how you’re doing,” McAllister says.

Teachers bring their classrooms one by one, and join the line.

This is how the people of Walter Douglas Elementary School send off their kids.

Finally, the buses pull out. Small hands wave out of the windows. Everyone waves back.

And then they’re gone.

“I wasn’t expecting to feel all that emotion,” says a young teacher, wiping her eyes.

A veteran teacher hears her, and puts a hand on her shoulder.

“Embrace it.”

About the project

Columnist Sarah Garrecht Gassen is writing about Walter Douglas Elementary School as part of the Star’s in-depth look at poverty in Tucson and how it affects kids.

Gassen spent time at the school in the Flowing Wells School District from mid-March through the end of the school year in May.

This is her third and final installment.

The first piece was published last Sunday and the second ran Thursday on the editorial pages. To read the previous columns go to azstarnet.com/walterdouglas

The Star’s weeklong news series on poverty begins Aug. 4.

Sarah Garrecht Gassen is a columnist and editorial writer. Email her at sgassen@azstarnet.com