Two Palestinians traveled more than 7,000 miles, through eight countries, to present themselves at the port of entry in Nogales more than a year ago.

They were seeking refuge in the United States.

“Because it’s a free country and you have the right to live as a human being,” Hisham Shaban told an immigration officer when asked why he sought asylum.

Both men have been in an immigration detention center in Florence, about 80 miles north of Tucson, since November 2014. In May, after an immigration judge found no evidence that they posed any danger, their bond was set at $9,000 each. They said they couldn’t afford it.

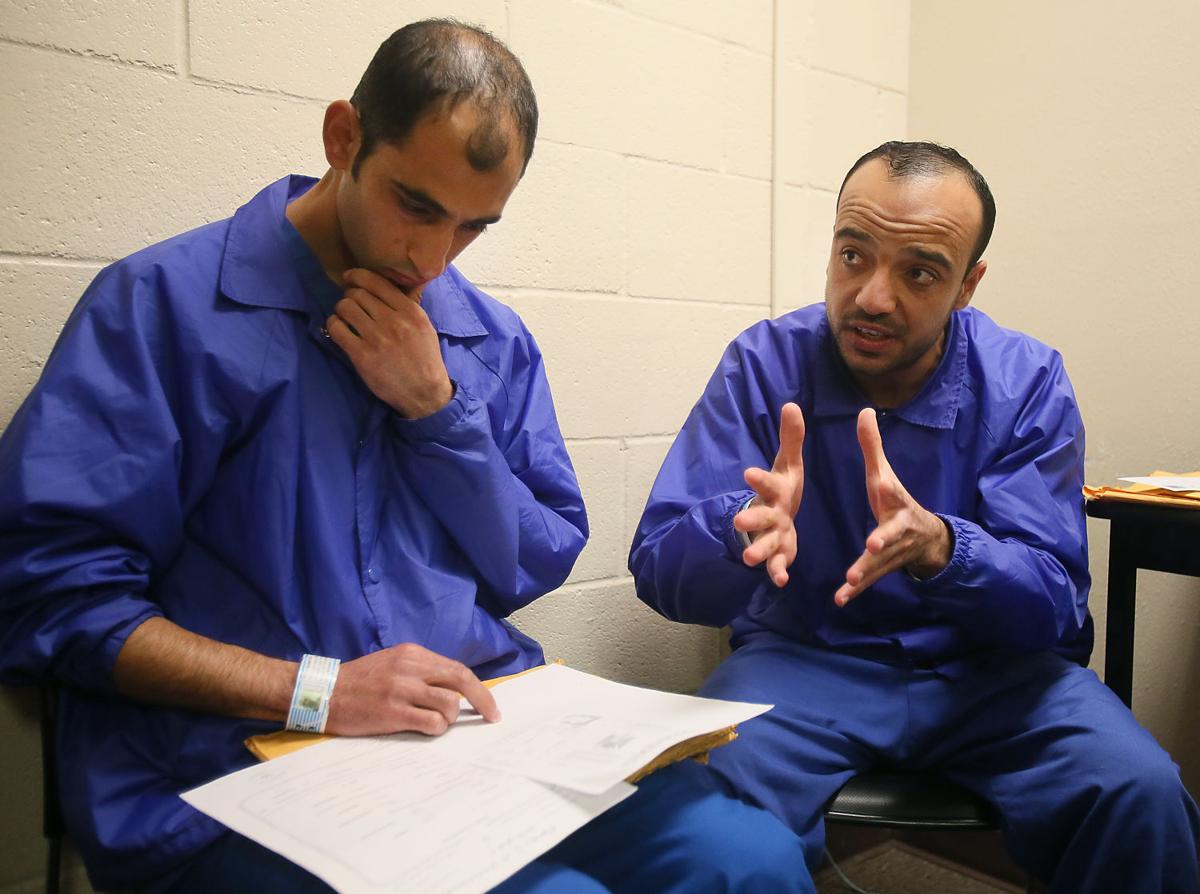

While the case of Mounis Hammouda, 29, is ongoing, Shaban, 32, is stuck in limbo since his asylum claim was denied in August because an immigration judge didn’t find credible his fear of returning home due to the general political and economic situation in Gaza. His attorneys, who weren’t representing him when the decision was made, believe procedural misunderstandings and lack of evidence to support his claim were contributing factors.

Since the United States doesn’t recognize the state of Palestine, it can’t deport Shaban back to Gaza, and the likelihood of other countries accepting him is slim.

But the U.S. can’t detain someone indefinitely, so Shaban’s pro bono attorneys will file a petition for his release during his upcoming six-month review, they said.

Shaban’s continued detention “seems to violate any principle we have as Americans,” said Liban Yousuf, civil rights director with the Council on American-Islamic Relations in Arizona and one of two attorneys representing both men.

And the possibility of sending him to a third country worries them. “We don’t know what will happen to him in any of these countries. We want him to either be released here under supervision or sent back to his family,” Yousuf said.

“They are refusing to release me here,” Shaban said through an interpreter from Florence, a tattered envelope with his case documents in hand, “and they are refusing to keep me here.”

STATELESS people

Worldwide there are millions of stateless people, some as a result of the collapse of their former countries or forced expulsion.

More than 700,000 Palestinians were displaced by the Arab-Israeli war of 1948. While Lebanon, Saudi Arabia and other Arab states with large numbers of Palestinians generally provide residence, there is no systemic path to citizenship, which affects their access to education, healthcare, social services and jobs.

There are about 4,000 stateless people in the United States, according to some estimates, many from the former Soviet Union and former Yugoslavia, said Maryellen Fullerton, an expert in asylum and refugee law at Brooklyn Law School.

Between 2005 and 2010, nearly 2,000 stateless applicants filed for asylum nationwide, Fullerton wrote in the Journal on Migration and Human Security in 2014. In Arizona, data from the immigration court system show that from 2011 to 2013 a handful of stateless people were granted asylum.

For those whose claims are denied but can’t be deported, such as Shaban, there is little recourse to get legal status here.

“Under basic principles of international law each state has to take back their own citizens if another state wants to expel them,” Fullerton said, “but if there’s no place to expel them to and they are going to be here in our society, it seems to me there has to be a way to get them regularized.”

The Supreme Court has ruled the U.S. can’t hold an immigrant indefinitely. The government has to review the cases of people it is trying to deport every six months. If there is no reasonable possibility that the U.S. will be able to deport the person, the government can release the individual “pending removal,” under an order of supervision, which could be checking in with immigration authorities periodically in person or via phone.

During these releases, stateless individuals generally can get a renewable work permit. This process keeps the stateless in a temporary and tenuous setting, Fullerton said, because they are in the U.S. without lawful status and are subject to the threat of removal at any time.

“They are unable to seek family reunification; unable to travel outside the United States for family or other emergencies,” she said.

Difficult travels

Shaban and Hammouda’s journey to the United States started in a refugee camp in Cyprus, where both lived separately for about three years after they left Gaza.

Neither had thought about seeking asylum here, they said, but life in the camp was increasingly difficult, with too little food and no job prospects or school. They didn’t have permanent legal status either and had to renew their conditional residency every year.

One day, a friend of Shaban’s mentioned he had relatives in Texas and how if they got to Egypt, they could fly directly to Mexico and come to the United States.

They didn’t get the visa to Egypt, but they flew to Venezuela, where Palestinians can travel more easily.

Through word of mouth from Palestinians they met along the way, they went from Venezuela to Nicaragua, Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico. They walked and swam across borders, were detained by immigration officials and tagged along with other migrants when they didn’t know what to do.

“We couldn’t find much help (in Nicaragua) when we heard in the hotel that a Cuban woman was headed to the U.S.,” Shaban said. “So we talked to her and she said she was going to be smuggled in.”

In all, they spent about $20,000 from relatives in Gaza who borrowed money and loans from friends in Canada, they said.

Customs and Border Protection didn’t provide the number of people who ask for asylum at Arizona ports of entry, nor would it make an official available for an interview, but Maha Nassar, an assistant professor in the University of Arizona in the School of Middle Eastern and North African Studies, is not surprised by the Palestinians’ journey.

“There’s an Arab, specifically Palestinian immigrant community, that goes back quite a ways in Latin America,” she said.

And the numbers are growing. Apprehensions of Asians and Africans in Mexico jumped from about 600 in 2012 to more than 4,000 last year.

“Historically, Latin America, particularly Mexico, has been a route for Arab immigrants going back to the 20th century, around WWI,” Nassar said.

“Credible Fear” in Gaza

Before they met in Cyprus, Shaban and Hammouda’s paths were very different.

While Hammouda was born and raised in Gaza, Shaban was born in Saudi Arabia, where his father worked.

Starting in the 1950s, Saudi Arabia went through rapid industrialization and needed labor, said Nassar, the UA professor. A lot of Palestinians went there for employment. But in the 1990s there was a nationalization movement, making it harder for non-Saudis to work and live there, she said.

Shaban’s family went back to Gaza in the mid-1990s, he said, where they had land. His mother was born in Egypt, part of the wave of Palestinians displaced in 1948.

“It was my homeland,” he said, “a place I had heard of but was strange to me.”

For Hammouda, Gaza is the only home he has known.

“Growing up, my mother would take me to the market and my father to marriages and parties,” Hammouda said. He was a mischievous child, he said with a smile, “I would give my mom headaches.”

But his life in Gaza was filled with periods of conflict.

In the early 1990s, when he was 4 or 5, he first realized the larger conflict around him.

“I would see the Israeli army on the streets, going inside homes, and I would run” he said. “I liked to play soccer, to go to school, not to be around weapons.”

The first Palestinian uprising calling for an end to Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza territories began in 1988 and went on for several years.

Also during the Gulf War, he said, “when Saddam Hussein hit Israel, people wouldn’t leave the house at all. We used to put plastic on all our windows and doors afraid of chemical weapons. We didn’t want to die.”

For Shaban and Hammouda, the turning point was in 2007, when Hamas, a rival political faction considered a terrorist group by the United States, took control of the Gaza Strip and Israel put in place economic sanctions.

One of the first steps toward gaining asylum is to show a “credible fear” of returning home. In his interview with U.S. immigration, Shaban, who sold jewelry and pictures on the streets for a living, described his neighbor being killed next to him. “All of the sudden there was a gunshot and it went into his brain and he was killed.”

Shaban was also beaten and threatened by neighbors affiliated with Hamas, part of a dispute among families, he said.

For Hammouda, the takeover had an even more dire impact.

His house was bombed and his father, who was a member of the political party Fatah and worked for the Palestinian Authority, was arrested and tortured by Hamas.

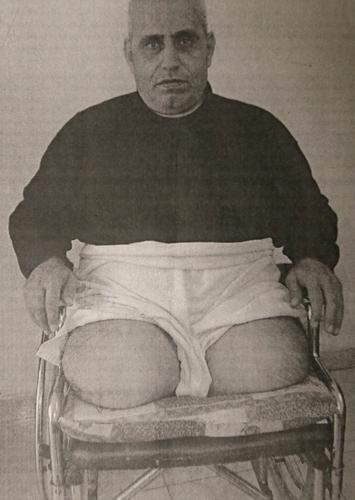

Mounis Hammouda’s father, Jamil Hammouda, who served as a member of the political party Fatah and worked for the Palestinian Authority, was arrested and tortured by Hamas. Hamas was one of Mounis Hammouda’s reasons for leaving.

During that time, UA professor Nassar said, “the political activists in the losing side fared badly.”

While his father was in critical condition in the hospital, Shaban said his family was threatened.

“I can’t leave the house, can’t work, can’t go to school, can’t do anything,” he said. “Why stay?”

In 2008 there was another war after a cease-fire was broken, which resulted in many people killed, Nassar said. “It was the first major bombardment of the Gaza Strip since 1967. A lot of the economy was also devastated.”

Shaban got out in 2010 and a year later Hammouda, who was in law school.

463 days and counting

It’s been 463 days since they presented themselves at the Nogales port of entry. They are counting.

They wear bright blue uniforms, orange slip-ons and a matching blue jacket. They speak with their attorneys through a glass wall, get a few hours outside and spend most of their time in their bunk beds with more than 60 men.

“Their days are pretty much set for them,” Yousuf said. “They can’t leave the premises, they are treated as prisoners. No one wants to spend that long in prison when they didn’t do anything wrong.”

They both passed their credible-fear interviews soon after they showed up at the port of entry, but they are now desperate for a resolution.

Asylum cases are some of the hardest in immigration law, according to attorneys, but initially neither man had representation, only assistance with paperwork from a local nonprofit.

Lawyer Yousuf and his colleague, Zayed Al-Sayyed, took their cases late last year after Gabriel Schivone, with the UA Students for Justice in Palestine, reached out to the Council on American-Islamic Relations.

“The fact that they were undocumented and Palestinian and in the United States seemed all unique, rare factors to me,” said Schivone, who got involved with their case after they asked for asylum.

“The length of the journey, the fact that they survived through Mexico was a miracle,” he said. He is still in touch with them a couple of times a week.

The attorneys’ immediate goal for Hammouda is to pay the $9,000 to get him out on bail so they can better work on his case.

For Shaban, whose claim was denied and waived his rights to an appeal, it’s already too late.

He didn’t know much of the asylum process in this country, Shaban said, “but I thought it would take us in. The consequences of what I did is being detained 15 months.”

Meanwhile, the conditions in Gaza have worsened since they left.

The economy is on the verge of collapsing, the World Bank reported last year. The territory, about the size of Detroit but with nearly 1.8 million people, has the world’s highest unemployment rate at 44 percent. For youth it’s 60 percent.

While there’s a small middle class and professionals, about 70 percent of the population in Gaza relies on humanitarian aid. There are constant power failures, limited access to clean water and limited movement.

In the last five months, Palestinian stabbings, shootings and vehicular assaults have killed 27 Israelis, The Associated Press reported. And at least 162 Palestinians, the majority of whom Israel says were attackers, have been killed by Israeli fire.

And their families are suffering, they said.

Hammouda said his father can’t work since his legs were amputated as a result of the torture, and his mother doesn’t work.

“They are currently living like hostages to Hamas.”