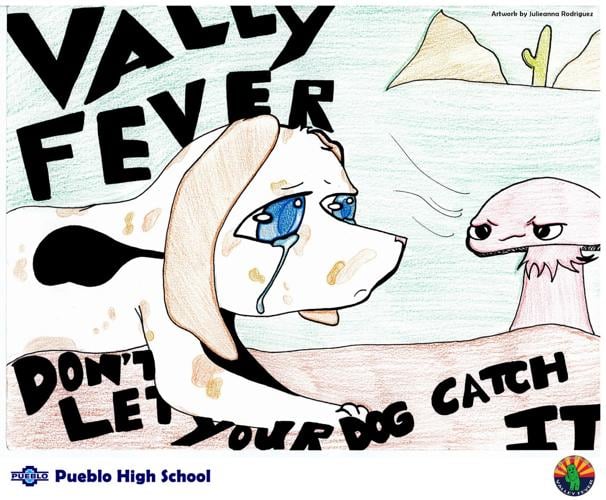

Pueblo High School teens studying biotech were having difficulty getting their peers in art class to care about valley fever — until they mentioned that dogs get the disease.

“To get people to be interested, you need to connect to their interests,” said Noemi Sumalinog, a 17-year-old Pueblo senior and student in Andrew Lettes’ advanced biotech class.

“Everyone cares about dogs.”

Indeed, the art students did care about dogs. And they were surprised to find out that valley fever is potentially fatal, has no prevention and no cure, and that it’s one of the most common diseases reported to the Arizona Department of Health Services every year. They also learned that the earlier that valley fever is caught in both humans and dogs, the better chance for a good outcome.

That knowledge helped the art students work with Lettes’ biotech students, and also bring in media, television and film students to create a visual-awareness campaign about valley fever. The south-side Tucson school has its own radio station that has broadcast information about the campaign, too.

As a result, the microcosm of the Pueblo community is now arguably getting more valley fever education than the rest of the state.

Arizona’s valley fever awareness consists of a passive, low-cost awareness effort — putting several public service announcements on a state website with the same message: “Cough? Fever? Exhausted? Ask your doctor to test you for valley fever.”

At Pueblo High, the awareness campaign is more aggressive.

“There’s been a lot of churning of energy around this campaign,” Lettes said.

Sick saguaro

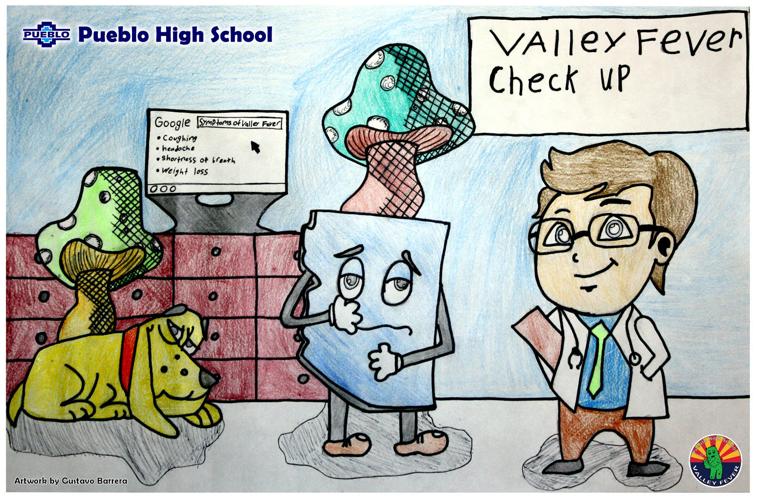

A centerpiece logo of the campaign is an illustration of a sweet-looking saguaro cactus with a face, shown coughing and in obvious pain.

The design, created by sophomore Kyle Elhard, was turned into a brightly colored button that has been a popular component of the campaign. Take a walk around the Pueblo campus on any given day and a number of students will be wearing them, Lettes and his students say.

The students are particularly proud that they gave one to a doctor at Banner - University Medical Center South who now wears it to work.

“What better mascot than a sick saguaro? People have an emotional bond with the saguaro cactus,” said Lettes, a former research associate at the University of Arizona’s College of Pharmacy who has been teaching biotechnology at Pueblo since 2004.

Lettes first got interested in valley fever in 2009 when one of his students spoke with an epidemiologist about the fact that there’s very low public awareness of the respiratory disease, which is endemic to Arizona.

Always one to back facts up with data, Lettes and his students developed a survey to track that awareness. His classes have been handing out the surveys consistently since 2009, surveying friends, family and members of the Pueblo High community.

Awareness since that time has been consistently tracking at about 20 percent.

Something had to change, and that’s when Lettes thought about taking an interdisciplinary approach to the problem.

“The traditional ways of looking at valley fever were not working,” he said.

That’s how students in Nallely Aguayo’s advanced art class got involved.

“I knew they were going to do well, but they went way above my expectations,” Aguayo said.

‘Very scary’

Biotech students explained valley fever to Aguayo’s class — emphasizing that it affects dogs, too — and the art students got to work on posters.

The top four were selected to be part of Pueblo’s valley fever awareness campaign, which includes a showcase box at one of the school’s entrances. Two of the posters included dogs.

The posters were shared on Twitter and caught the eye of leaders at the University of Arizona’s Valley Fever Center for Excellence. The UA center then featured the posters on its Facebook site.

“Art catches people’s attention,” said 18-year-old Gustavo Barrera, whose colored pencil design includes a doctor, a lethargic-looking dog and colorful mushrooms to represent the cause of valley fever — coccidioides fungal spores that are found in the soil of the southwestern U.S. and in parts of Mexico, Central and South America.

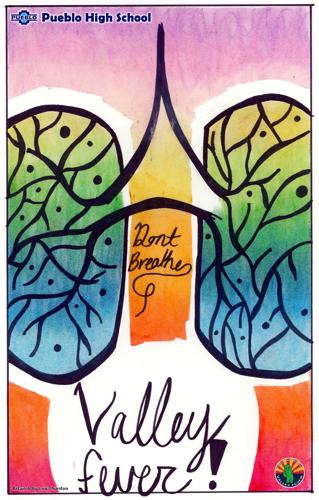

Lya Thurston used a smudge effect with pastels to create her valley fever poster, which shows a pair of infected lungs. The smudging is representative of how the sickness spreads — attaching to the lungs and growing from there, said Thurston, a 16-year-old junior.

“It’s Arizona’s disease, but it’s not well-known, which is very unfortunate. It’s very scary,” Thurston said.

Thurston has spoken to her family and friends about valley fever and learned about people and dogs who have suffered from it.

“My friend’s co-worker had it and was bedridden for eight weeks and dropped so much weight,” Thurston said.

Measuring data

Biotech students Elizzabeth Esparza, Alondra Cordova and Sumalinog are cautiously optimistic that the awareness campaign has made a difference. Not just a difference, a statistically significant difference.

Esparza, an 18-year-old senior, said she sees a lot of information on television about cancer, but nothing about valley fever. She thinks the state should be paying more attention to it.

Sumalinog agrees. She thinks a campaign in airports would help warn visitors to Arizona who might not know anything about valley fever. Not to scare them away — just to inform them in a positive way, she said.

For example, Sumalinog has learned that she is at higher risk for valley fever because she is Filipino.

Studies have already found higher rates of disseminated valley fever in men than in women, and in African-Americans and Filipinos versus other ethnic groups. Also, certain blood groups — B and AB — have been identified in studies as more likely to get the disseminated version of the disease.

After the artwork was placed in the Pueblo showcase in the fall, the students conducted another one of Lettes’ valley fever surveys to gauge awareness of the disease.

Awareness had, for the first time in eight years, increased. The survey showed an awareness level of more than 50 percent.

The results were encouraging. But Lettes has taught the students to be skeptical about data, so they will need to conduct the surveys several more times before the results can be considered statistically significant, he said.

Science Night

At the school’s recent annual Family Science Night, Sumalinog, Esparza and Cordova wore white lab coats and spoke to adults and kids about valley fever.

The students had a beanbag toss that highlighted valley fever symptoms, a valley fever info board and a poster of a crying dog that said, “I can get valley fever.”

They also conducted awareness surveys with 100 attendees and Sumalinog had a long conversation with a construction worker about the risk of valley fever in his profession.

The students won’t stop there. They’ll sell their buttons at the Pueblo High Fiesta April 13, and will conduct 100 more surveys, too.

But even Lettes, ever the skeptic, thinks the initial results are promising.

“The component that was missing was the art,” he said. “Collaboration is so hard to do. We’re always too busy. But we need to do more of it.”