A team of astronomers led by Ian Crossfield of the University of Arizona has verified the existence of 104 planets in data collected by NASA’s K2 space telescope mission.

Among them are four planets orbiting a low-mass star, two of which could have temperatures comparable to Earth’s. The planets are 20 percent to 50 percent larger than Earth and presumed to be rocky.

“Whether they are in the habitable zone for certain awaits a more-detailed study, but they certainly have the potential to have temperatures similar to what we have on Earth,” Crossfield said.

The four potentially rocky planets orbit an M dwarf star (K2-72). It’s half the size of our sun and about 181 light years away in the direction of the constellation Aquarius. The planets are so close to their sun that they complete their orbits in 5.5 to 24 Earth days.

But, because their sun’s radiation is weak compared to ours, temperatures could be comparable to Earth’s, especially on the two planets farthest away with 16- and 24-day orbits.

Crossfield is lead author on a paper describing the discoveries, published online in the Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series.

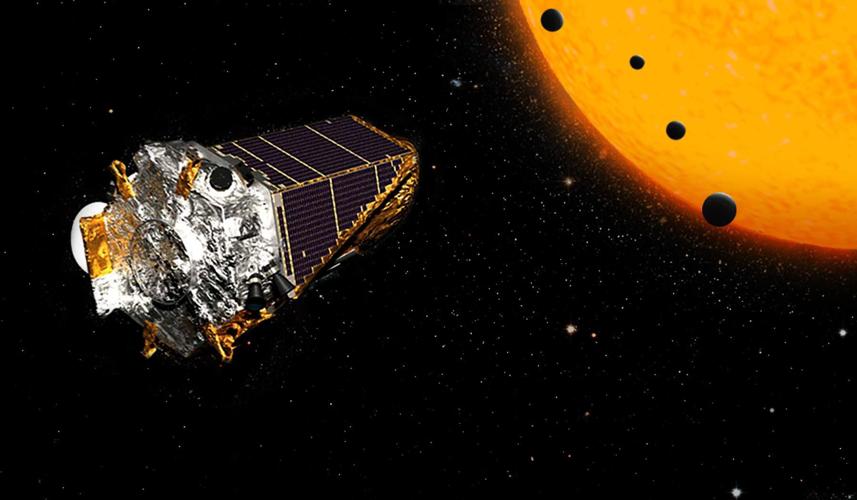

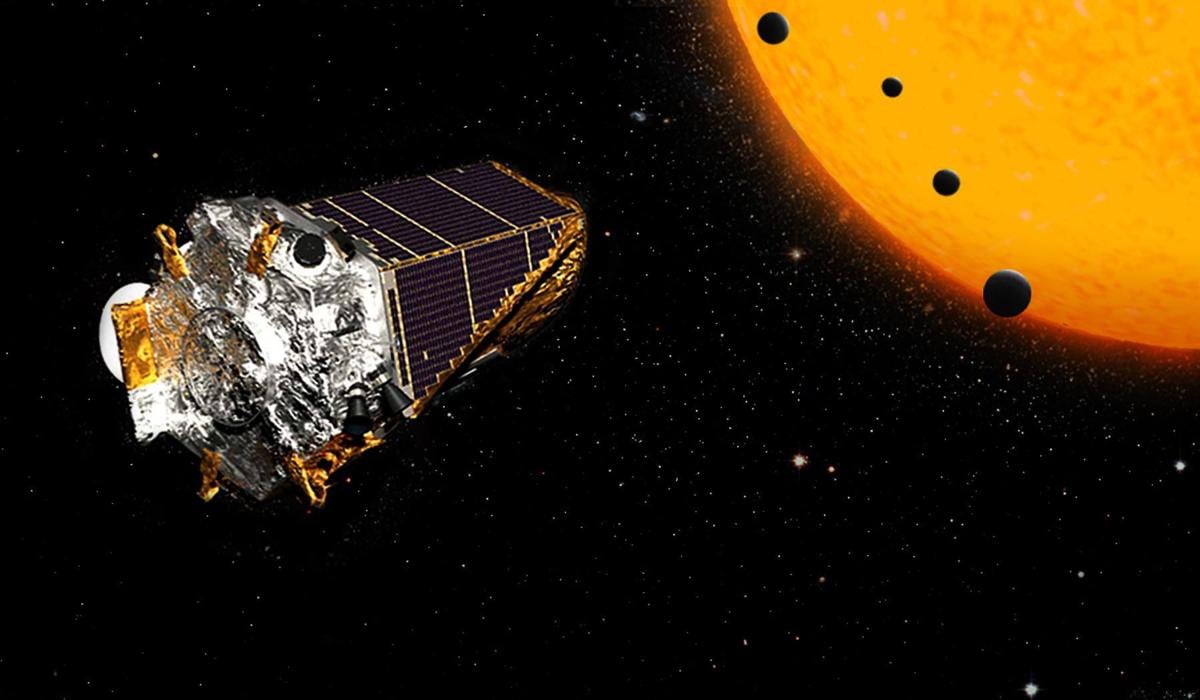

NASA’s K2 mission, now completing its second year, is an extension of the Kepler Space Telescope’s original mission, which watched a narrow patch of the Northern Hemisphere sky for four years, recording dips in the light measurements of sun-like stars that signal the potential existence of orbiting planets.

It found more than 2,000 exoplanets before losing its ability to remain stationary. In the extended K2 mission, NASA engineers are using the sun’s heat and the spacecraft’s engines to point its telescope toward new targets, including a large population of smaller, cooler stars, many of which are closer to our solar system.

Crossfield worked with an international team of astronomers to find and characterize the 104 planets announced Monday by NASA.

After finding the candidate planets with K2, they did follow-up observations, including spectral observations, of the suns they orbit with some of the largest telescopes on Earth — the Keck and Gemini telescopes in Hawaii and the Large Binocular Telescope on Mount Graham in Arizona.

The planets themselves can’t be seen, said Crossfield, but the stars provide clues to their size and composition.

“The discovery of a transit tells you something like a planet might be there and tells you the size of the planet relative to its star. Until you study the star better, you don’t know too many details of the planet.”

The planets in this study are all from the first year of K2 operation, Crossfield said. It has now completed its second year and a similar number of new planets is currently being vetted.

Crossfield said he expects the team to find at least 400 new planets over the four years of the K2 mission. He said the study is providing targets for future exploration with the next generation of space telescopes.

More powerful space telescopes could answer the questions raised by these discoveries, Steve Howell, project scientist for the K2 mission at NASA’s Ames Research Center, said in a NASA statement.

“These targets allow the astronomical community ease of follow-up and characterization, providing a few gems for first study by the James Webb Space Telescope, which could perhaps tell us about the planets’ atmospheres.”