A team of astronomers led by University of Arizona graduate student Kevin Wagner has discovered a planet with three suns, using a new planet-finding instrument on the Very Large Telescope in Chile.

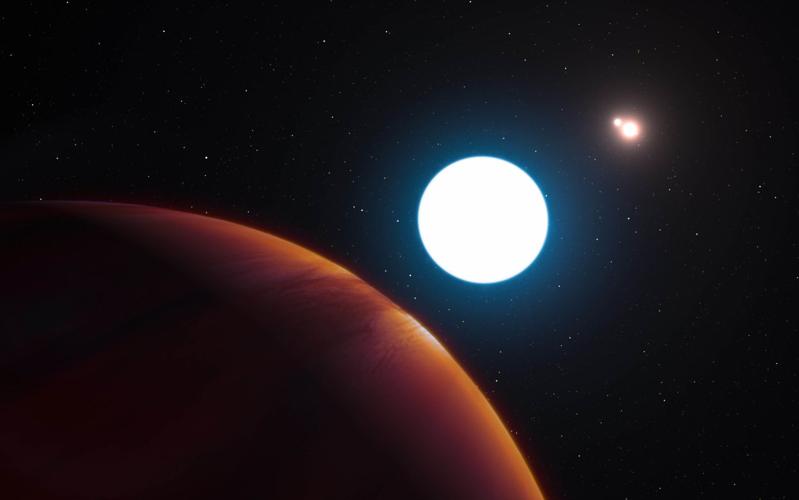

The planet, about four times the size of Jupiter, orbits the main star in the system at a distance about twice that of Pluto from its sun — 80 times the distance from the sun to Earth.

An observer on the planet would see three suns rising and setting each day. For about a quarter of its 550-day orbit, it would be in perpetual sunshine.

The planet is located about 320 light-years from Earth in the constellation Centaurus. Its discovery was reported Thursday in the journal Science.

Wagner, a first-year graduate student at Steward Observatory, leads the Scorpion Planet Survey, which is looking for planets around 100 young stars in the Milky Way galaxy.

Directly imaging planets is difficult. The light from a star makes it impossible to see small, faint planets, so the survey looks for giant planets in young solar systems that move in wide orbits around their stars.

“We’re looking for planets with heat left over from their formation that we can image,” Wagner said, “trying to constrain the population of giant planets.”

Most surveys target single stars, said Wagner, but he is looking at a mix of single and binary stars. Wagner thought he was looking at a known binary star system during his observing last June, but found that the smaller point of light was actually two stars.

“In that first observation, we resolved stars b and c for the first time, but also discovered a planet.”

It was the first planet discovery for SPHERE, which can erase the blur of the atmosphere with what it calls “an extreme adaptive optics system” and can mask the overwhelming light of the star with a coronagraph, allowing the much dimmer planet to be imaged.

SPHERE, which stands for Spectro-Polarimetric High-contrast Exoplanet REsearch, also takes spectra of the planet’s emissions, which made it possible for Wagner to determine with that first look on June 12 last year that he was observing a planet and not some distant star in his field of view.

“It has a spectrum that a planet would,” he said, with the signature of methane and water vapor.

The signal was a little “noisy” at first, Wagner said, and it wasn’t the first time he thought he’d seen a planet, so he didn’t jump up to spread the news.

Wagner works from home most days, receiving data from Chile, where telescope operators point the telescope at his selected targets.

“It’s kind of the surreal experience of exploring space from your couch,” Wagner said.

The planet’s existence was verified in subsequent observations of its movement with the triple-star system, and better spectral data.

Information gathered in the planet hunt will be useful in Wagner’s other tasks at Steward Observatory, where he is part of a NASA-funded team called Earths in Other Solar Systems, headed by astronomer Daniel Apai, Wagner’s adviser and a co-author on the paper.

Apai is currently in Europe meeting with other exoplanet hunters. He said in an email that understanding how giant planets such as this one form will guide the search for habitable planets.

“Giant planets have very powerful impact on any habitable Earth-like planets: it is important that we understand how they form and in which system we can find them,” he wrote.

Most of the discovered exoplanets orbit single stars, Wagner said, because that is where astronomers have looked for them.

The paper argues that it is “due to the assumption that such planetary systems would either be disrupted or never form, as well as the increased technical complexity of detecting a planet amongst the scattered light of multiple stars.”

This new planet apparently prevails in its orbit despite those disruptions, Wagner said, suggesting that binary systems may be a fruitful target for exoplanet searches.

“If we need to revise our giant planet formation models, that will also lead to changing the strategy for searching for habitable planets,” Apai wrote.

Apai noted in his email that this is Wagner’s second major discovery in the first year of his doctoral program. Last fall, in the same survey of young stars, Wagner imaged a two-armed spiral disk around a young star.

“This is extremely rare, even at the forefront of astronomy,” Apai wrote.

“For me, one of the highlights of working as a professor at the University of Arizona is that I get to work with some of the smartest and most motivated young astrophysicists and planetary scientists in the world — and Kevin is clearly among the very best.”

Kaitlin Kratter, a UA assistant professor of astronomy is a co-author of the paper, along with Melissa McClure and Markus Kasper, European Southern Observatory; Massimo Robberto, Space Telescope Science Institute; and Jean-Luc Beuzit, principal investigator of SPHERE.