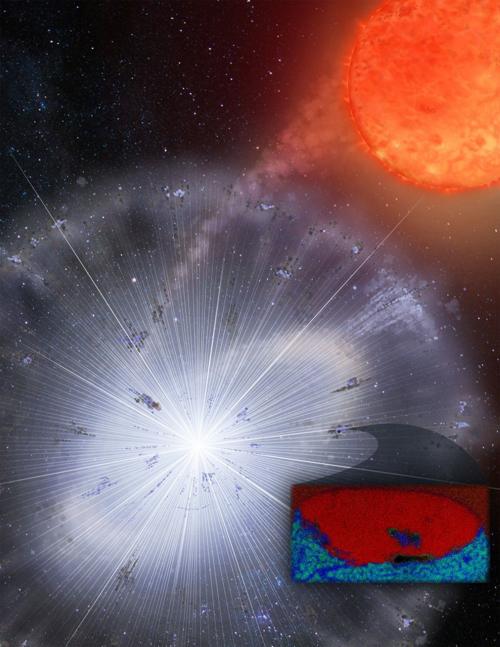

The discovery of a tiny speck of stardust, the remnant of a long-gone star, could hold clues about our solar system’s birth, say UA scientists involved in the discovery.

Found inside a meteorite collected in Antarctica, the microbe-size speck represents actual stardust, most likely hurled into space by an exploding star before our own sun existed.

“As actual dust from stars, such pre-solar grains give us insight into the building blocks from which our solar system formed,” said Pierre Haenecour, a University of Arizona scientist and lead author of a paper on the discovery.

Dubbed LAP-149, the dust grain represents the only known assemblage of graphite and silicate grains that can be traced to a specific type of stellar explosion called a nova, the scientists reported.

Remarkably, it survived the journey through interstellar space and traveled to the region that would become our solar system some 4.5 billion years ago, perhaps earlier, where it became embedded in a primitive meteorite.

Pierre

Haenecour

The meteorite is part of the collection of the UA Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. Haenecour will join the laboratory as an assistant professor in the fall.

Taking advantage of sophisticated ion and electron microscopy facilities at the LPL, a research team led by Haenecour analyzed the microbe-sized dust grain down to the atomic level.

“It’s fascinating that we can hold in our hand a grain that’s older than the solar system,” Haenecour said.

Measuring 1-25,000th of an inch, the carbon-rich graphite grain revealed an embedded speck of oxygen-rich material.

Unfortunately, the grain doesn’t contain enough atoms to determine its exact age. Researchers said they hope to find similar, larger specimens in the future.

“If we could date these objects someday, we could get a better idea of what our galaxy looked like in our region and what triggered the formation of the solar system,” said Tom Zega, scientific director of the UA’s Kuiper Materials Imaging and Characterization Facility and associate professor in the LPL and the UA Department of Materials Science and Engineering.

“Perhaps we owe our existence to a nearby supernova explosion, compressing clouds of gas and dust with its shock wave, igniting stars and creating stellar nurseries,” Zega said.

It’s an old, very old, story — and one that will continue indefinitely into the future.

Members of the research team studying the speck of stardust put it this way in a news release:

“Since shortly after the Big Bang, when the universe consisted of only hydrogen, helium and traces of lithium, stellar explosions have contributed to the chemical enrichment of the cosmos, resulting in the plethora of elements we see today.”