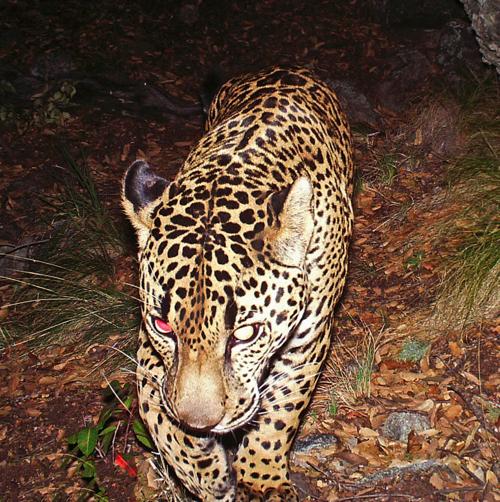

An adult male jaguar — the only known wild jaguar in the United States — found a home in the Santa Rita Mountains and didn’t just visit from Mexico, a new study concludes.

Remote cameras put into the wild for a research project photographed the jaguar — later dubbed El Jefe — 118 times over 34 months, says the study, done by University of Arizona and U.S. Geological Survey researchers. On average, the jaguar was photographed once every 7.9 days in the Santa Ritas southeast of Tucson.

After the federally funded research ended last June, the jaguar, now believed to be about age 7, continued to show up regularly through mid-October of last year on photos. Those were taken by remote cameras operated separately under the direction of UA and the nonprofit group Conservation CATalyst, with support from the activist Tucson-based Center for Biological Diversity.

Since then, El Jefe has gone AWOL. Authorities and environmentalists say they don’t know where it went. One heavily discussed possibility is that the animal headed south to breed in Sonora, where female jaguars are known to live, although Melanie Culver, lead investigator of the UA/federal study, said it’s possible it went elsewhere in Arizona.

No female jaguars have been documented in this country since one was shot in the White Mountains in 1963. Jaguars are listed as an endangered species.

Researchers presume this jaguar is a resident in the Santa Ritas “because he was photographed by our cameras every month of the year from November 2012 to February 2015,” the study said.

The Star obtained a draft of the study this week from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under the federal Freedom of Information Act. Culver, who works for the U.S. Geological Survey, said she expects that agency to release a final version to the public at the end of next week. The wildlife service oversaw the research project, which was financed by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security.

Other findings of the study, which put remote cameras in 16 Southern Arizona mountain ranges:

- The cameras took 13 photos of three male ocelots over the three years, which is notable because the study wasn’t designed to detect ocelots, which are also listed as endangered. Seven photos of one ocelot were from the Santa Ritas. Six photos of two ocelots came from the Huachuca Mountains.

- Of the 16 mountain ranges, the Santa Ritas had the biggest diversity of species. That could be because that range drew by far the most research effort — 57 camera sites. But the Coyote Mountains, southwest of Tucson near Three Points, tied for the third highest species diversity with only three camera sites. So the number of sites and species aren’t necessarily linked.

- El Jefe had an estimated home range of nearly 35 square miles, unusually small for a jaguar. Its range is probably small because the area has a high density of jaguar prey such as deer and the predator has no competition. The study said this estimate should be taken cautiously since the study wasn’t designed to determine this.

The study started and finished in an atmosphere of controversy. When the three-year, $771,000 effort was announced in 2011, then-Gov. Jan Brewer denounced it as a waste of taxpayers’ money that should be spent on border security.

The wildlife service and environmentalists said the study would be a worthwhile effort to gain information about a rarely seen animal in this country. Since the middle 1990s, five jaguars have been photographed or otherwise documented in Southern Arizona and Southwest New Mexico.

Now, to many opponents of the proposed Rosemont Mine, the jaguar has become a symbol of the habitat that would be cleared for the mine. Rosemont would be built on private and public land in the northern Santa Ritas, near where the jaguar and one ocelot have been captured on camera.

The wildlife service concluded in two rounds of biological reviews that the mine won’t jeopardize the jaguar’s existence or illegally destroy its habitat. But a lower-level service biologist and the Center for Biological Diversity have disagreed.

Randy Serraglio, a conservation advocate for the center, said the new report proves the Santa Ritas’ jaguar habitat is worthy of protection.

“Jaguars are under a lot of pressure in Mexico from poaching and development,” Serraglio said Wednesday. “They need places to disperse and be safe. The whole point of critical habitat is to provide places for them to do that.”

The findings refute the service’s view that El Jefe “doesn’t matter because he wandered into the U.S.,” said Serraglio, a longtime mine opponent. “They keep talking about the important ones being in Mexico, but this cat is connected to the ones in Mexico.”

The wildlife service’s Steve Spangle, however, said his training as a biologist tells him a jaguar that isn’t breeding isn’t contributing to the population, and the service looks at populations, not individuals. All this jaguar’s presence shows is that the habitat is good enough to support a single animal, he said.

“He’s an unpaired male,” Spangle said. “It’s a good sign for ecosystem health. It is not a significant factor for the overall population.”

Researcher Culver said that while the jaguar could have gone south to breed, it’s also possible that it’s a non-breeding animal from the Mexican population who simply left it.