Anxiety and depression are about the future and the past, so, “be present,” Tucson yoga instructor Hilda Oropeza urged her class on a recent Thursday night.

Oropeza, the owner of Mindful Yoga Studio, said she has long known what several recent scientific studies have concluded — that in addition to offering physical and spiritual benefits, yoga may help mitigate depression.

Five different papers presented at the American Psychological Association’s annual convention in Washington, D.C., in August found that people who suffer from depression may want to look to yoga as a complement to traditional therapies.

And earlier this year, a study by Harvard and Columbia researchers published in The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine found that people with major depressive disorder had a significant reduction in symptoms during a 12-week intervention that included Iyengar yoga classes. The study looked at 30 participants who ranged in age from 18 to 64.

Some medical experts say the results are promising but merit further study to determine, among other things, how much yoga one needs to reduce depressive symptoms.

Yoga vs Exercise

“What makes yoga different from exercise in general is, for one thing, the focus on the breathing practices, which really can make a difference,” said Amy Weintraub, a Tucson resident, a longtime expert in yoga and mental health, and founder of the LifeForce Yoga Healing Institute.

“Yoga can meet the depressed client where they are with a slow, gentle practice that helps them build their energy.”

The therapeutic effect of yoga on depression was a little-researched concept when Weintraub first published her book, “Yoga for Depression” in 2004. Weintraub’s own struggle with depression prompted her interest.

During a year of daily yoga in 1989, she was able to tolerate an increasingly lower dosage of antidepressants, eventually going off them altogether. She did that while under the supervision of a psychiatrist, she stressed.

“When I first wrote the book, I got some pushback. I’m not a clinician, I’m not a psychotherapist,” Weintraub said.

But that pushback quickly turned into interest from clinicians and others curious about integrating yoga with traditional medicine, she said.

Now there is a whole new generation of researchers more open to alternative therapies — often they are yoga practitioners themselves, she said.

Similarly, leaders at the University of Arizona’s Center for Integrative Medicine have found that an increasing number of health providers who train in the center’s fellowship program are yoga practitioners themselves, said Dr. Hilary McClafferty, a pediatrician and center fellowship co-director.

The fellowship includes instruction in yoga to encourage its use in medical settings, she said.

“Yoga can be defined as a synergy of mindfulness, breathwork and movement, and the breath is a very potent part of it,” she said. “Physiologically, working with the breath is one of the few ways people can voluntarily tap into the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems and help themselves modulate their stress.

“It is an ancient practice. Yoga has been around for thousands of years and now when you look at the science we understand it’s really influencing the physiology and balance of the nervous system.”

Weintraub, who gives workshops on yoga and mental health around the world, founded the Lifeforce Yoga Healing Institute in Tucson and also developed the LifeForce Yoga Practitioner training for yoga and health professionals.

The instructor training certifies professionals, including social workers and physicians, as yoga teachers to those suffering from depression, anxiety, chronic pain and a history of trauma.

Sound and breath

Weintraub tracks evidence-based research on yoga’s mental-health benefits through a LifeForce newsletter and said the research is not merely validating — it also informs LifeForce training, which is constantly evolving, she explained.

Being anxious and depressed is not anyone’s true nature, she stressed. A simple breathing practice can bring us more clarity, she explained.

“The yoga philosophy and the practices themselves allow us to see we are more than our mood or than our story,” she said. “When you practice yoga with attention to breath and sensation, you are in the present moment — so much more connected to presence and wellness and not your story or mood.”

McClafferty, of the UA’s Center for Integrative Medicine, said yoga is being used in pediatric hospitals around the country for children with challenging medical conditions.

“You’ll see kids in wheelchairs with IV pumps who are learning yoga to manage their stressors and pains,” she said. “It has such a good risk-benefit ratio — it is a low-risk therapy.”

Indeed, yoga is safe and probably more accessible than some other alternative treatments because it can be taught and practiced in groups, said Dr. Ole Thienhaus, who is chair of the University of Arizona’s psychiatry department.

“What is unclear is how effective it is and for whom. For that to be answered, studies are needed. That’s easier said than done,” he said. “There is really no true double-blind design possible, so studies to date are more naturalistic, and results less reliable than those of conventional drug trials for instance.”

Depression is not a unitary concept, he emphasizes. It’s a manifestation of widely differing, underlying problems. Thus, there is never going to be a one-size-fits-all cure for it, he said.

complementary treatment

“The findings are still inconclusive, but promising. It seems likely that yoga will be more helpful for some people with depression than for others, as is the case with other interventions,” he said. “It is also likely that yoga will often be used in conjunction with other treatments, rather than as a stand-alone.”

Studies and increased acceptance of yoga’s positive effect on depression should not be considered medical advice, Weintraub stressed.

One thing the studies have yet to conclude is exactly how much yoga one needs, though the evidence suggests the more the better. Weintraub estimates the positive effects of yoga wear off after 72 hours.

Chronic depression

At the American Psychological Association convention, researchers from the Center for Integrative Psychiatry in the Netherlands presented data on the potential for yoga to address chronic or treatment-resistant depression.

In one study of 12 patients who had experienced depression for an average of 11 years, Dutch researchers found weekly yoga sessions of 2.5 hours each over nine weeks resulted in lower scores for depression, anxiety and stress throughout the program. The study also found that benefit persisted four months after the training.

“I would see, based on the research to date, yoga being part of the emphasis on mindfulness, as a helpful way to prevent or reverse mood dysregulation,” the UA’s Thienhaus said. “It is part of a broader approach that addresses many aspects of lifestyle management, rather than being a new treatment replacing conventional ones.”

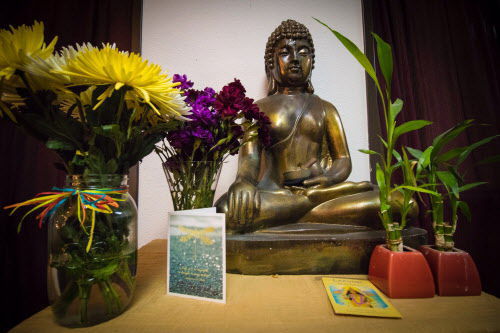

Oropeza, of Mindful Yoga, purposefully created a yoga studio where classes are gentle and slow, “to give people an opportunity to connect with what is important to them,” she explained. Such classes can be more difficult for students because it pushes them to see the busyness of the mind, she said.

“The primary reason for yoga is to calm and quiet the mind,” she said. “Mindful means sitting down, noticing what is happening with the body, mind and heart...It’s moving from an external to internal focus.”