If you are diagnosed with leukemia — a blood cancer — and are a person of color, you are less likely to find a matched bone-marrow donor to help rid you of the disease.

But for the past two years, Dr. Emmanuel Katsanis at Banner-University Medical Center Tucson has implemented a method of treatment that has only recently been accepted in the United States to help shrink the health gap.

It is called a haploidentical transplant, or haplo for short. The method allows for a transplant with a stem-cell donor with only half the matching proteins, called human leukocyte antigen typing, rather than full or near-perfect matches, which are typically sought out.

No matter what transplant method is used, it’s important to search for a stem-cell donor with similar human leukocyte antigens. Matching antigens trick the body into welcoming the helpful, foreign cells without trying to destroy them.

“Haplo is relatively new,” he said. “It’s exciting, but for us … we have evidence that it has impacted our (diverse) community.

“Haplo has really increased the survival of minorities.”

Katsanis is also a University of Arizona professor of pediatrics, medicine, pathology and immunobiology; the Louise Thomas Chair in Pediatric Cancer Research; and chief of the Division of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology.

He took over as director of the UMC Blood and Marrow Transplant Program in 2012. “I looked at our outcomes and I felt that they needed to be improved,” he said.

Since 2015, Katsanis has performed haploidentical transplants on 10 pediatric patients. All 10 are still alive and leukemia-free. In haploidentical transplants in adults, the results also appear better than near-perfect donor matches, Katsanis said.

In addition to bringing haplo to Tucson, Katsanis has begun a clinical study, based on research on mice published in 2016, to test a more efficient and safe chemotherapy.

Currently, doctors use a drug called cyclophosphamide, but the drug works so well in suppressing the donor stem cells from attacking the recipient’s body, that it also suppresses the donor stem cells from attacking the leukemia.

The drug Katsanis is testing, called Bendamustine, does not have these overreaching effects in mice, and he wants to prove the same in humans.

FINDING A DONOR

Ideally, a patient will have a perfectly matched sibling.

When that’s not the case, doctors seek matches outside of the family. If there are none, they will typically use donated stem cells with a one-antigen mismatch for a near-perfect match.

Patients are more likely to find a match within their racial and ethnic groups because antigens are inherited.

Minorities have a difficult time finding a match for multiple reasons including a lack of volunteers registering in the National Marrow Donor Program (NMDP).

And the more donors, the merrier.

While the donor list finally mirrors the U.S. population, when also including one-antigen mismatches, it’s important for minorities to be overrepresented because there is more antigen variation within minority populations than in whites, according to the NMDP, caused by the genetic shake-up of migration, colonization and immigration.

Haplo can be used as an alternative method. The advantage is that it gives minorities more options when they must rely on a transplant and an unrelated donor cannot be found quickly.

Because people get a set of human leukocyte antigens from each parent, they will always be a half match.

There’s also a 50 percent chance that someone’s sibling will be a half match, a 25 percent chance they will be a perfect match and a 25 percent chance they inherited the opposite antigens.

But there are many minor human leukocite antigens that are not tested for, and people are more likely to share those with family members than unrelated donors, Katsanis said, another advantage of haplo.

MEETING MAIYAH

Maiyah has played sports all her life, so the annual physical before her junior year of high school was routine.

But Micheria Harris, a nurse and Maiyah’s mother, felt that the glands in Maiyah’s neck were a little swollen. She asked her husband, Walter, retired Air Force of 22 years, to have the doctor do blood work, just in case.

“We got a call maybe 10:30, 11 that night,” Walter Harris said. On the line was Dr. Dawn Sorenson of Banner Health in Maricopa, where the Harrises now live. She asked him to take Maiyah to urgent care right away to redo her blood work.

First thing in the morning, they got another call.

“Chronic myeloid leukemia,” Maiyah said, almost under her breath, recalling the moment as she sat next to her dad on the couch in their living room, her once long dark hair now stubble on her scalp.

Maiyah, now 17 years old and a senior in high school, was diagnosed in July 2016 with CML, which is usually only found in older people.

Walter Harris thought they should go to the Mayo Clinic for treatment. “They’re big, there’s a lot of press on them,” he said.

But his wife works at Banner Desert in Mesa and wanted to try Dr. Erlyn Smith. “I guess her and (Katsanis) work together so when we signed up for her, we also signed up for Dr. Katsanis.”

“When we first went down to Tucson, we just got a really good feeling,” Walter Harris said.

Everything happened quickly after that, Walter Harris said. Days later, Maiyah was taking chemotherapy pills. But because of a mutation she had, which the family would learn about only later, the different kinds of oral chemo she was taking for months were not working.

“This whole process was rough because she didn’t have any symptoms,” Walter Harris said. “So (the doctor is) telling me she’s sick, but I don’t see any symptoms.”

Around December, they realized that a bone-marrow transplant was her only hope, and so they began searching for a match.

They looked within the family first.

Maiyah has a 19-year-old brother who just joined the Air Force, and is currently in technical school in Texas, training for the same position his dad had before him. He will be stationed at Davis-Monthan, just like his dad was.

Unfortunately, he was a “terrible” match, Walter Harris said.

So, just in case, they began looking for an unrelated donor. Because the Harris family is black, the chances were already slim.

THE NUMBERS

The likelihood of white patients finding a perfectly matched donor is about 80 percent, and the chances increase dramatically if they are looking for a one-antigen mismatch, raising the likelihood to 97 percent.

For Hispanics, Native Americans and Asians, it’s about 40 percent for full matches or about 80 percent or less for one antigen mismatches.

Black patients, like Maiyah, have the worst odds: There’s about a 20 percent chance they will find a perfect match and a 76 percent chance they will find an unrelated mismatch, according to a 2014 paper in the New England Journal of Medicine cited by the NMDP.

In the spring of this year, Maiyah’s aunt created a Facebook page to promote the donor program, bolster the odds of Maiyah finding a match and share Maiyah’s progress with friends and family.

“Our support system was really, really awesome,” Walter Harris said.

“Most of our friends and relatives got tested,” he said, but as far as finding a match, “it just didn’t happen.”

TAKING A CHANCE

After the unfruitful search, the Harris family and Katsanis decided to undergo the haploidentical transplant via one of the parents.

While Walter Harris was reflecting on how he and his wife decided who would donate, tears swelled and his voice caught. He covered his face.

“She was always the one, you know, that sacrifices, and with me being in the military, you know, she always had to put her career dreams on hold.”

He smiled at his daughter through his tears and nudged her playfully. “She always says I’m a big old crybaby.”

Walter agreed to donate his bone marrow to his daughter. He, as a parent, was a half match.

The haplo method is still new and being studied, so more conservative doctors are less likely to use it. Still, Katsanis believes that in 10 years, haplo will be used more often than finding an unrelated donor.

Haplo outcomes are now similar to matched related and unrelated, Katsanis said.

But it’s still fairly new and therefore, many doctors who study it are careful about selection, said Dr. Jeanne Palmer, program director for the adult bone-marrow transplant at the Mayo Clinic, which is also the same program as Phoenix Children’s Hospital.

The practice of being so careful could skew the results of the long term outcomes, she said.

There are only a handful of places in Arizona doing haploidentical transplants. Palmer said that they started doing haplo off-protocol around the year 2012.

As of now, the Mayo Clinic prioritizes unrelated matches and one-antigen mismatches, Palmer said. Only then does haplo become an option.

“With one caveat,” — Palmer said — “if you need a donor quickly.”

Katsanis and his colleagues at Banner UMC on the other hand, believe that haplo is preferable to one-antigen mismatch transplants based on their outcomes so far.

“Pretty much each of these are a miracle in terms of what we’ve managed to do over 10 years ago,” Katsanis said. “And I have patients that I remember — if this was now ... they would have been alive because haplo was not even an option back then.”

CATCHING UP

Things were at their worst for the Harrises around the time of Maiyah’s transplant. She was very sick because of the high doses of chemo.

But she never complained, wrote her mother on the Facebook page. Maiyah was wearing multiple Wonder Woman T-shirts throughout the process.

Maiyah was initially enrolled in Katsanis’ study to test Bendamustine, but she had to be removed because she didn’t get enough of her dad’s stem cells. She was battling with side effects of chemotherapy before and after the transplant.

She was in the hospital for seven weeks for her transplant. During that time, Walter and Micheria Harris would take turns making the 100-mile drive to Tucson from Maricopa.

Walter Harris said the biggest relief was when Katsanis announced that Maiyah’s body had accepted his stem cells.

“That means it worked. I mean, you’re still not out of the woods, but it means it worked.”

That was in July of this year.

“I’m fine now,” Maiyah said in a bubbly voice earlier this week.

“It’s just tough for her being cooped up,” Walter Harris said. She wears a mask to keep from getting sick.

Maiyah is taking online high school classes, but can return to school once her immune system is strong enough. Katsanis wants to wait until after peak flu season has passed, aiming for February, to return to school and complete her senior year .

“She’s getting back to normal and we’re arguing quite a bit,” Walter Harris said, laughing.

On Thursday, Harris drove Maiyah to her bimonthly check up.

Katsanis scrolls through her medical charts and data from returned blood samples. “You continue to be in remission with no evidence of the disease.”

“Disease,” Maiyah scoffs quietly, sitting forward with her arms folded on her lap.

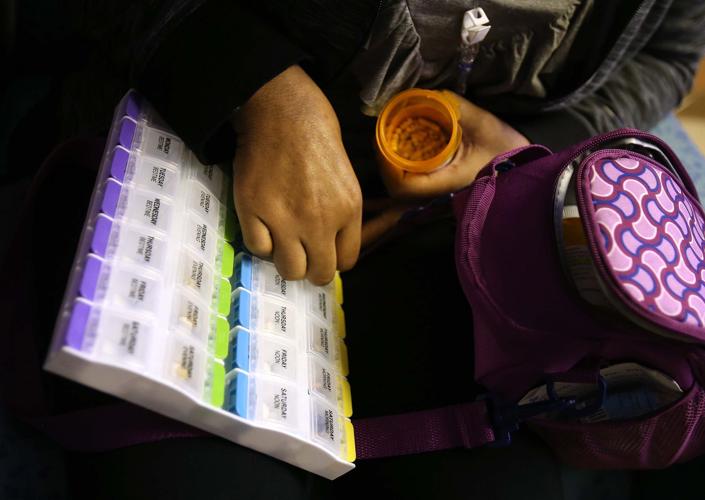

Katsanis scanned a list of medications she’s taking, and said she could stop taking one of the many pills she carries in a purple lunch box.

“Yes!” she said, with a clenched fist in victory. Then she began plucking out the pills she didn’t need anymore from her weekly pill tray.