NASA wants to find habitable planets around relatively nearby stars.

Daniel Apai’s mission is to make sure that it builds the right kind of space telescope for that task and points it in the right directions.

Apai, a University of Arizona professor with joint appointments at Steward Observatory and the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory, heads up a NASA-sponsored effort to define optimal conditions for life on exoplanets and identify the kinds of stars that they orbit.

The Earths in Other Solar Systems team is part of NASA’s Nexus for Exoplanetary System Science program, whose ultimate goal is identifying, imaging and characterizing planets that might bear the biosignatures of life.

The work involves a variety of specialists in astrophysics, planetary science, physics, chemistry, geology, biology and materials science. At UA that involves the unification of astronomy and planetary sciences and partnerships with the National Optical Astronomy Observatory and other universities and institutions.

The search necessitates a reconsideration of accepted ideas on how planets form around stars. Until recently, the only model we had was our own solar system.

Turns out, says Apai, that our particular sun and planetary system may be the exception rather than the rule.

That became clear in the past decade as NASA telescopes and ground-based observatories started to discover and image exoplanets.

They found super-Earths and hot Jupiters but few Earth-sized rocky planets, and even fewer candidates in the “Goldilocks,” or habitable zone — far enough from their star that water wouldn’t just boil off and close enough to avoid being totally encased in ice.

In its first year of operation, EOS has published ten refereed papers outlining progress toward a new understanding of planet formation and a new definition of habitability.

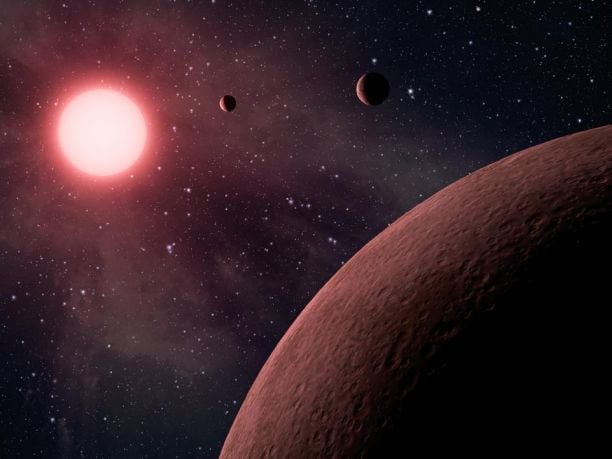

One recent one, published in Astrophysical Journal, suggests that we should be looking at stars unlike our own sun. Gijs Mulders, a post doctoral researcher at the Lunar and Planetary Lab, ran a statistical analysis of exoplanet data gathered by NASA’s planet-hunting Kepler Telescope.

Kepler had mostly observed sun-like stars, but Mulders’ analysis suggested that it may have been more fruitful to observe smaller ones. Those smaller stars, known as M dwarfs, have about half the sun’s mass.

They seem to form more planets than their larger cousins, Mulders discovered. And those planets are closer to their stars.

Close is not always good. Consider Mercury, where scientists don’t bother to look for life signatures because of its extreme heat. But low-mass stars don’t give off as much heat. The “habitable zone” is closer to the star.

Ilaria Pascucci, one of the paper’s co-authors, said that makes it easier to observe the star’s planets with two of the methods for detecting exoplanets — transit, or measuring the dimming of the star’s light when a planet passes in front, and radial velocity, which measures the wobble caused by the gravitational force of the orbiting object.

“We were quite pleased because one implication is that the number of planets like Earth in the habitable zone could be larger,” Pascucci said.

Location, however, is not the sole measure of habitability. The team also seeks to understand how planets form in other solar systems, including how they might gain access to water and biological materials.

Pascucci said the group is looking at forming and formed planetary systems around stars ranging from half the sun’s mass to twice its mass.

So, simultaneous investigations are going on at some of the largest telescopes on Earth and in space. The team is not planet hunting, per se, but trying to understand where to look by examining solar systems in formation as well those with potential exoplanets.

“We’re looking for planets, and for planetary systems in formation,” said Apai.

The group is also using supercomputers to simulate solar-system formation based on those observations.

It is also examining meteorites, which Apai called “time capsules of the early solar system. We’re looking for planetary building blocks.”

“Basically we are looking for a recipe to cook a planet,” he said.