PHOENIX — Think someone’s getting unfairly harassed by police?

Well, now there’s an app for that.

The American Civil Liberties Union of Arizona is offering a program for Android and Apple phones that makes it easy to record situations someone witnesses — or even if they are part of the encounter.

That may not sound like much, given that most smartphones and tablets already can do that.

But here’s what makes the Mobile Justice app different: The video is automatically uploaded to ACLU cloud storage the moment the recording is stopped. And that means it would not be destroyed even if the phone is taken away or damaged.

ACLU spokesman Steve Kilar said his organization has seen a pressing need for such an application. He said there is a concern about excessive use of police force, particularly in minority communities.

“Obviously, we’ve seen a number of viral videos, very disturbing videos, put on the Internet over the last year showing excessive use of force,” Kilar said. “We wanted to put a tool in people’s hands that allows them to capture these incidents and, in the end, hopefully, reduce them.”

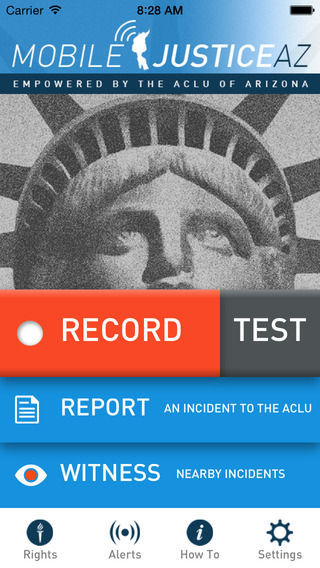

Kilar said it’s designed to be simple.

Load the app and a large red “record” button appears. Hit that, and the screen becomes a viewer of what is being recorded.

Touch anywhere on the screen, the recording stops and the video is automatically uploaded.

“The upload happens very quickly,” Kilar said, something that’s particularly important if someone tries to take the phone away, turn it off — or just stomp on it.

Kilar said the application is primarily designed for bystanders.

“It is obviously within people’s rights to videotape police interactions that they themselves are involved in,” he said. “But it can be dangerous.”

Kilar said people need to tell an officer what they are doing before reaching into a pocket, purse, vehicle or anywhere to retrieve a phone. But he suggested not getting into an argument if an officer objects.

“They can’t challenge abusive behavior on the street,” Kilar said. “That could be very dangerous for both them and the police officer.”

The ACLU is asking those who upload a video to follow up and fill out a brief form detailing what they saw. Kilar said that will help his organization classify, review and keep track of the videos.

He said “hundreds of thousands” of videos already have been uploaded from similar aps the ACLU has rolled out in other states. Kilar said, though, he knows of no situations where the videos have been used to file complaints against officers.

But Kilar said even those videos could prove helpful in the long run.

“If we are getting a lot of videos relating to one particular police force ... that does provide us with an opportunity to go to the police force and say, ‘Hey, we’ve been getting a lot of complaints about this particular type of behavior,’” Kilar explained. And in some cases, he said it’s possible the videos could be used to support a class-action lawsuit against a particular agency.

“We’ll certainly be looking for certain patterns of behavior,” he said, including racial profiling.

The ACLU does have some specific experience with such profiling.

In 2006, it got the state Department of Public Safety to provide public access to its traffic stops. That ended a 5-year-old lawsuit filed by the ACLU and others that contended the DPS, particularly in Northern Arizona, was singling out minorities.

A 2003 Arizona Daily Star review of more than a quarter-million DPS records indicated the agency’s officers searched Hispanics more often than Anglos — about 1 in 25 compared with 1 in 48. By contrast, officers found contraband on 1 in 5 Hispanics compared with 1 in 3 Anglos.