Altaf Engineer is a new University of Arizona assistant professor in — you guessed it — architecture.

And while he’s not an engineer, he is as interdisciplinary as his title suggests: In addition to his assistant professorship, he also began working this fall as a research faculty member in the UA Institute for Place and Wellbeing, which integrates medical research and design practices to address how built spaces affect human psychology and physiology.

The institute is “extremely unusual,” said Esther Sternberg, founding director. There’s a much longer history between public health and urban planning than on individual buildings and bodies.

The institute is a collaboration between the College of Medicine, the Arizona Center for Integrative Medicine and the College of Architecture, Planning and Landscape Architecture.

The institute recruited Engineer partly because he co-founded a nonprofit designing rapidly deployable and dignified housing for displaced people.

“What he’s done is so timely,” Sternberg said, “and it speaks to his commitment to social justice.”

Before coming to the UA this fall and earning his Ph.D. in 2015, Engineer designed college and university buildings at a firm in Washington, D.C., when he met Amro Sallam and they dreamed up Architects for Society.

They quickly amassed a worldwide team of 14 in early 2015, and a year later, the group became a nonprofit.

“Most of us were mid-career architects, so we’d done all kinds of buildings and always wanted to do something more meaningful on our own,” Engineer said.

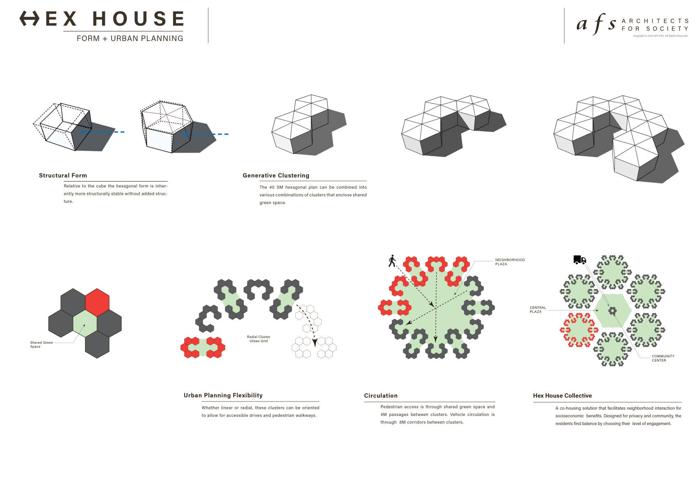

The central focus of the nonprofit has been the Hex House, an emergency shelter that can also serve as long-term housing. The concept won multiple design awards in 2016.

“We developed the Hex House because we were passionate about helping disadvantaged communities,” Engineer said. “It’s not only refugees of war, but also refugees of natural and manmade disasters of all kinds — even recent flooding in Houston,” should FEMA choose to implement the design.

The nonprofit collaborated with an architecture studio class at Chalmers University of Technology in Gothenburg, Sweden, to generate ideas for refugee housing

Yousef Oqleh, a board chair for Architects for Society and design architect and urban designer at AECOM in Dubai, United Arab Emirates, collected the information about refugees and their needs for the class by traveling to the Zaatari refugee camp — now the fourth-largest population center in Jordan.

“Dignified housing was the biggest goal,” Engineer said. “We realized from studying the conditions of the refugee camps that they adjust and adapt and make the most of living in tents, but that doesn’t mean that they are living in equitable housing like the rest of us.

“So if you enjoy a kitchen or toilet in the house, so should they,” Engineer said.

Each 500-square-foot, six-sided Hex House is made of structurally insulated panels with two bedrooms, a kitchen, a bathroom and a living space. The honeycomb floor plan is more structurally stable than a rectangular layout.

The architects also aimed to be sensitive to “the particular culture that a lot of these people come from,” Engineer said. “They’re used to community living,” and the honeycomb shape is easily clustered into a communal space.

Houses can also be built off the grid because of solar panels, water tanks and compostable toilets and can include adjustable legs for uneven terrain, slopes, running water or flooding.

The houses can also be made wheelchair-accessible.

“We won’t just ignore and ship units; we’d think about what each site needs,” he said.

To foster funding, the team built prototypes in Minneapolis and Amsterdam this fall.

An individual house can be built in less than a week with trained help. Each house costs about $50,000 to $60,000, but the team would like to get it down to about $25,000 per unit, Engineer said.

The team is not planning any new projects just yet. “For now it’s trying to implement solutions somewhere.”

“Government emergency and disaster-relief agencies, global refugee agencies such as UNHCR, and other nonprofits and NGOs would pay for them,” he said. “But forming partnerships and implementing projects together with NGOs — in my opinion — has the most potential since we would have very similar goals and objectives.”

At the UA, part of Engineer’s work is educating the next generation of architects as well as creating a master’s of science in architecture that will kick off in fall 2018. The program will focus on health and built environment.

His dissertation and work done by the Institute for Place and Wellbeing is focused on studying the performance of employees in the workplace and how to create environments for optimal health.

Sternberg’s work with the institute included using environmental sensors within the building and wearable sensors to track people’s physiological reactions to the built environment, and will continue along this path with the addition of Engineer.

Engineer said when he began down the architectural path, he had no idea he would be doing what he is today.

“I just gravitated toward things I liked doing.”

His last name was passed down from his great-grandfather who, like many others during British rule of India, named himself by his profession. He was an electrical engineer.

Growing up in India, he took an early interest in art, which developed into an interest in architecture.

“Art, I think, raises questions, but architecture offers solutions.”

Engineer hopes to put those solutions into action.