One century and 10 months ago, Arizona made its first of 61 trips to play basketball at New Mexico, the Wildcats’ nearby rival for decades in the Border and Western Athletic conferences.

Some 450 miles separate the schools. The drive can take six or seven hours; a charter flight maybe 50 minutes or so.

It was a small price to pay for a lively regional rivalry that fans and players alike enjoyed.

But the fun came to a 19-year-halt on Jan. 16, 1999, the day time froze at the The Pit.

Or, more specifically, the day the seconds froze.

Four seconds and six-tenths of another were left on the clock after Arizona took a 78-77 lead on a jumper from Jason Terry. The game was nearly over, appearing to be a big road victory for a relatively young team that had lost the bulk of its 1997 national championship squad in the spring of 1998.

Then the Lobos inbounded.

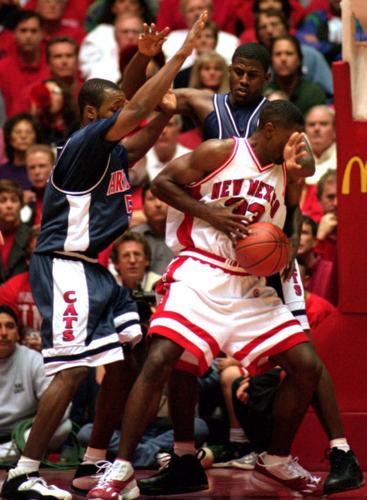

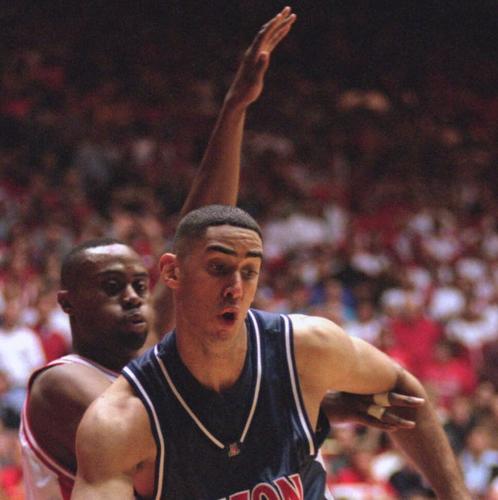

Point guard John Robinson II took the ball downcourt, put down some moves near the top of the key to help spread the Arizona defense, then threw a lunging pass to Damion Walker under the basket.

With time still remaining, Walker converted the game-winner at the buzzer over the outstretched arms of Arizona forward Michael Wright.

“That was the world’s longest four seconds,” Arizona guard Ruben Douglas said.

It was more than that, Olson said. It was about a shot-clock operator who didn’t hit the button until after Robinson caught the ball and began dribbling, he indicated, and about officials who botched other parts of the game.

“If anyone wants to know about the series,” Olson said indignantly, “the home game next year — that will be the end of it.”

Olson kept his word. His Wildcats hosted the Lobos in 1999-2000 because that game was already under contract, but never did return to Albuquerque to play the Lobos, though they did venture back to the Pit for a couple of NCAA Tournament wins in 2002.

Even Dave Bliss, then New Mexico’s coach, wondered how it all happened.

“I was ready to shake Lute’s hand,” Bliss said after the game. “We’ve run that play in practice, and we’ve done it in six seconds. But we didn’t have six seconds.”

Maybe he was winking inside, or maybe he wasn’t, but Walker spelled out the X’s and O’s.

In a fast-moving play, Walker said, he was the second option.

“It’s a play called ‘guard blast,’ ” Walker said. “The guard tries to get the ball to half court as quick as possible and draw the defense to him. If he doesn’t take the shot, he dishes to me.

“It worked out textbook.”

The Wildcats disagreed. While the normally glib Terry stayed largely quiet, saying Olson had told players not to say anything negative, several of them expressed quiet disbelief that it was allowed to work at all.

“I thought (Robinson) was going to shoot it,” Wright said. “I didn’t think he could take the ball down there, dribble it, and then pass it. You can’t do all that in four seconds.”

Walker’s shot effectively erased what would have been a game-winner by Terry. By this midseason point, it was clear Arizona’s leaders were Terry and fellow senior A.J. Bramlett, a native of Albuquerque who spent much of his homecoming game mired frustratingly in foul trouble.

If allowed to, Terry might have aired as much of a grievance as Olson, if not more.

“He wanted the last shot — he told the coaches he wanted to take the last shot,” UA forward Gene Edgerson said after the game. “This is his senior year and he wanted to win this one, especially for A.J., his buddy, his pal. It really hurt him. He thought he made the winning shot.”

He did, the way Olson saw it.

“If I were the officials, I would be ashamed,” Olson said afterward. “It was on national TV, so it will be out in front of everybody. It’s just disgusting to see this — to see kids being taken advantage of, but that’s what the Pit is all about.”

Olson added a zinger.

“Now you know why people don’t want to play here,” he said.

Three days later, at his weekly news conference, Olson was still fuming.

Here’s how he described it then:

“The kid catches the ball after the basket, takes a step and a dribble before the clock goes on,” Olson said. “It’s a game that obviously could have gone either way. But either the (timer) guy is very inept or very dishonest, one or the other.”

Olson had other complaints. Among them, he said the Wildcats were thrown off during a timeout with 22.5 seconds left. New Mexico had taken a shot that missed the rim and backboard, and the shot clock expired, leading Arizona to believe it would have possession after the timeout.

But the official play-by-play ruled the Lobos had only used up 33.3 of the 35 seconds allowed.

“We’re there setting up our strategy, and suddenly they say, ‘Oh, we got a problem, and it’s still their ball,’ ” Olson said.

Olson was so angry over the time clock management that, when asked in the press conference what his young team learned in three close games over the previous week, couldn’t help but veer back to that moment.

“Well, I think they realize that the game at New Mexico really could have been in the win column, if the timer starts the clock when the guy catches the ball,” Olson said. “It’s like Dave Bliss said, they’ve never been able to do that in less than five seconds. But no, you didn’t have your timer starting the clock, either. You probably had a manager. … Three times in the last minute the guy put the knife to us.”

A replay of the game today might have the Wildcats winning by a point, the way UA coach Sean Miller describes it.

He’s heard the story about that 1999 game, too, and wonders.

“If I were coach Olson I’d probably feel the same way if that happened,” Miller said. “But that was then and this is now. It’s a whole new dynamic now with the scorer table, the monitor where you can check and double check. It’s made our game better, so that if a situation like that occurs it’s correctable.”

But it wasn’t corrected. The score from Jan. 16, 1999, reads: New Mexico 79, Arizona 78.

It is permanently etched into the history books of both schools. And the story behind it has been permanently etched in the minds of so many players, fans and officials who were part of the game or watched it that day.

Even as the Lobos’ first-year head coach, Paul Weir has heard the story, too.

He was glad he did.

“I think it’s great,” Weir said. “I think it’s great that that’s the way basketball has been and hopefully will continue to be down here. There’s heated rivalries. There’s heated emotions. It’s basketball in the Southwest. I tell recruits all the time that it’s the greatest place in America to come play basketball because of the history and the tradition of all the programs here in the Southwest.

“When you hear stories like that I actually smile knowing that it’s such a special place to be and coach basketball.”

Miller and then-New Mexico coach Craig Neal agreed to a thaw in May 2015, signing a two-year series that began last season. Each team would play each other on its home court, and the Wildcats held serve easily in the opener last season, winning 77-46 at McKale Center.

On Saturday, the Wildcats will return the favor by playing the Lobos in the Pit for the first time since that 1999 game.

There are no more games scheduled. There is no Border Conference or WAC making these games happen anymore. And, with the Wildcats now able to zip home on charter jets from anywhere, there’s no real incentive for Arizona to play New Mexico over any other nonconference team.

But Weir, who was an assistant at New Mexico State when Miller scheduled three games against the Aggies between 2010-2013, is hopeful the UA coach will someday agree to more with the Lobos.

Since arriving at UA in April 2009, Miller has signed off on regional home-and-home deals with San Diego State, UNLV, New Mexico, New Mexico State, UTEP and Texas Tech.

“He’s been awesome,” Weir said. “I mean, there’s very few coaches in this region who would be willing to schedule the games that he has. There’s a lot that goes on in this profession in these with coaches and contracts, and they may never want to play a UTEP or a New Mexico or a New Mexico State.

“You have to tip your cap to him. It really means a lot to programs on the other end and I think it also really helps basketball in all of our communities, particularly as attendance starts to become more challenging each and every year for all of us.

“It behooves us to play more games like this.”